Site Navigation

Contents of Thesis ack'ments - Preamble - Introduction -Accessibility - W3C/WAI - LitReview - Metadata - Accessibility Metadata - PNP - DRD - Matching - UI profiles - Interoperability - Framework - Implementation - Conclusion - References - Appendix 1 - Appendix 2 - Appendix 3 - Appendix 4 - Appendix 5 - Appendix 6 - Appendix 7

In an information era, everyone has to have, one way or another, an equal right to information if they are to participate equally in the information age. Currently, there is frustration with the available content, the access to it, and the way in which this is being managed for what are many more people than usually appreciated, who, for one reason or another, have special needs.

At the Museums and the Web 2006 conference, one word had the power to abruptly silence a lively discussion among multimedia developers: accessibility. When the topic was introduced during lunchtime conversation to a table of museum web designers, the initial silence was followed by a flurry of defensive complaints. Many pointed out that the lack of knowledgeable staff and funding resources prevented their museum from addressing the “special” needs of the online disabled community beyond alternative-text descriptions. Others feared that embracing accessibility in multimedia meant greater restrictions on their creativity. A few brave designers admitted they do not pay attention to the guidelines for accessibility because the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 1.0 standards are dense with incomprehensible technical specifications that do not apply to their media design efforts. Most importantly, only one institution had an accessibility policy in place that mandated a minimum level of access for online disabled visitors. Conversations with developers of multimedia for museums about accessibility were equally restrained. Developers frequently blamed the authoring tools for the lack of support for accessible multimedia development. Other vendors simply dismissed the subject or admitted their lack of knowledge of the topic. Only one developer asked for advice on how to improve the accessibility of their learning applications. (Constantine, 2006)

About 15% of Europeans report difficulties performing daily life activities due to some form of disability. With the demographic change towards an ageing population, this figure will significantly increase in the coming years. Older people are often confronted with multiple minor disabilities which can prevent them from enjoying the benefits that technology offers. As a result, people with disabilities are one of the largest groups at risk of exclusion within the Information Society in Europe.

It is estimated that only 10% of persons over 65 years of age use internet compared with 65% of people aged between 16-24. This restricts their possibilities of buying cheaper products, booking trips on line or having access to relevant information, including social and health services. Furthermore, accessibility barriers in products and devices prevents older people and people with disabilities from fully enjoying digital TV, using mobile phones and accessing remote services having a direct impact in the quality of their daily lives.

Moreover, the employment rate of people with disabilities is 20% lower than the average population. Accessible technologies can play a key role in improving this situation, making the difference for individuals with disabilities between being unemployed and enjoying full employment between being a tax payer or recipient of social benefits.

The recent United Nations convention on the rights of people with disabilities clearly states that accessibility is a matter of human rights. In the 21st century, it will be increasingly difficult to conceive of achieving rights of access to education, employment health care and equal opportunities without ensuring accessible technology. (Roe, 2007)

Work is taking place in many quarters to alleviate this situation. People have talked about universal access but then modified it to be universal design when they found the former impossible, and then universal usability when they thought this at least meant taking everyone's needs into account, even if they could not be satisfied, and in this thesis, the focus is what is called 'AccessForAll'. It is an approach, and it differs from the others in that it relates directly to the individual needs and preferences of individuals, mostly as determined by themselves, in contrast to relying solely on benevolent specifications of what people might need or want, and when.

For at least ten years, there has been an international effort to discover and promote what is called universal design specifications for the Web. It is clear now that universal design alone cannot solve the accessibility problem. A flexible approach including usability in a sort of 'tangram' model could significantly improve the results (Kelly et al, 2006). The approach now being proposed brings together the metadata management of resources and the authoring of these resources, in a dynamic model with the user's personal needs and preferences themselves being adaptable, so that there is a better result. Finally, as it is not possible to define absolutely what will be accessible for users, as it is only possible to specify processes, not their outcomes, it is suggested that the framework should be expressed within a process model. Furthermore, in an Australian context for example, where the failure of a defence to lack of accessibility leads to a prosecution for discrimination to compensate the victim, it really only makes sense to talk about processes when specifying standards. In other words, while there is evidence that the current approaches to accessibility are not working and cannot work in isolation, used within the proposed framework, they should become more effective.

An ongoing examination of the available literature repeatedly reveals two significant things: a common approach to accessibility based on universal accessibility, as promoted by the World Wide Web Consortium [W3C], and a significant failure of that approach to make a sufficient difference.

Almost one in five Australians has a disability, and the proportion is growing. The full and independent participation by people with disabilities in web-based communication and information delivery makes good business and marketing sense, as well as being consistent with our society's obligations to remove discrimination and promote human rights. (HREOC, 2002)

Estimates of accessibility are as low as 3% (e-Government Unit, UK Cabinet Office, 2005) even for important public information. Estimates for those with needs in terms of access in Europe right now show 10-15% with disabilities and growing as the population ages (European Commission Report Number DG INFSO/B2 COCOMO4 – p. 14.). and Microsoft commissioned research suggests the benefits will be enjoyed by 64% of all Web users (Forrester Inc., 2004). In 2004, the Disability Rights Commission [DRC] reported on the accessibility of 1,000 UK Web sites (DRC, 2004). They showed that 81% of Web sites failed to meet minimum standards for disabled Web access and later claimed, at a press conference, that sites prima facie considered to demonstrate good practice, when fully tested by the DRC, in fact failed to satisfy minimum standards. These reports have been supported by a 2007 United Nations Report (Nomensa, 2006).

Lack of satisfaction with the progress led to the need for a new framework for accessibility that recommends the use of metadata to facilitate discovery and delivery of digital resources that are accessible to individuals according to their particular needs and preferences at the time of delivery. Needs arise when a user has a constraint that renders information inaccessible to them such as when a highly mobile person using a telephone cannot use a small scale map that cannot be displayed on their tiny low-resolution screen or a blind person requires Braille. Preferences are considered to be indicative of suitable responses to constraints for the individual user. It should be noted that some users have very specific needs and no preferences whereas other users may be satisfied by any from a range of preferences.

Even if such a process were not implemented, there is a significant problem for the W3C in the development of their specifications for accessibility. If a resource is not touchable, as is the case for a locked historical digital image, for example an early digital image of something where the image is of historical importance, and not accessible to users who cannot access it visually, W3C either cannot have a specification saying it must be accessible or introduce exceptions to their specifications. The latter course is not attractive to those responsible but the former can work if the original resource can be associated with an accessible alternative and this could be done through the use of the URI of the original resource and the location of this URI within or associated with the accessible alternative. It is asserted it would be most easily guaranteed by the use of metadata and so, at the very least, the use of metadata is critical to the potential for accessibility standards. (see emails with Gregg around 21/9/2007)

The context for the new work is the so-called 'Web 2.0' (O'Reilly, 2004); the current Web is not different from the original Web except that it is now a distributed, collaborative environment with the potential to support AccessForAll accessibility. As William Gibson wrote, “the future is here, it is just unevenly distributed.” (wikipedia William Gibson, 2006). This dissertation proposes a framework for adaptability metadata for the future Web with the intention that many of the currently available, suitable resources can be subsumed into the accessible Web and, with relative ease, new resources can be made available.

The new work has been undertaken in a collaborative context. There have been many publications that are relevant to the work, many of which have been written or co-authored by the author of this dissertation. The author records such collaborations and asserts that without them, no standards could have been established. Further, the author asserts it is a strength of the work reported that it has been undertaken in an international, collaborative environment. But that also makes the role of the author complex and necessarily, the dissertation complicated.

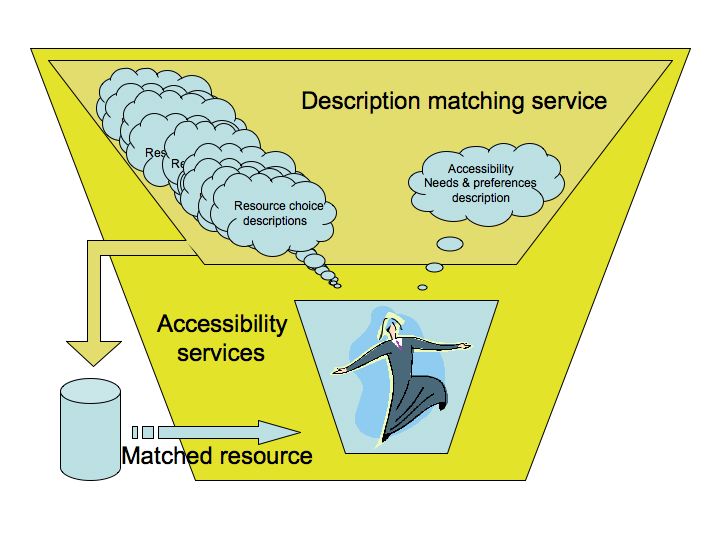

The author's thesis is that a new framework is required to understand the possibilities made available by the collaborative work to develop a new way of managing accessibility that, in a sense, merely complements the usual approach. Within this framework, the author asserts, the new possibilities make an enormous difference. It is the framework that this dissertation provides. The work that has made the framework possible is simple, at one level. It just involves adding a matching service to resource delivery process, but all that entails is complicated by the context, the stakeholders, the technology, and so on. The proposed framework provides a way to make sense of the new process in the complex context. The dissertation does not detail the results of the work as that is evident in publicly available international standards; it provides the framework for understanding the reasons for the work, its base and implications, how it relates to other work and how it might be used.

The dissertation is motivated by a decade of work towards accessibility on the part of the author and an extensive international community, that has not fulfilled the on-going aims of that work. Instead of continuing to try to force results by continually pursuing the same approach, the author and others have taken advantage of the changing context in which they are working, and undertaken work to exploit the features of the new environment that will bring to bear many more human and other resources to tackle the problem.

The more that information is mapped and rendered discoverable, not only by subject but also by accessibility criteria, the more easily inaccessible information for the individual user can be replaced or augmented by information that is accessible to them. This, in turn, means the less pressure there is on the individual author or publisher of information to make their information accessible, the better. This is important because, as is shown (see ch.2), it is burdensome, unlikely to happen, and not guaranteed anyway, that information presented in what are known as universally accessible resources will, in fact, be accessible to a particular individual user.

Widespread-mapping of information depends upon interoperability of individual mapping, the interoperability of the mapping or, in another dimension, the capability of combining distributed maps in a single search source. The ancient technique of creating atlases from a collection of maps is similar (Ashdowne et al, 2000). Being able to relate a location on one map to the same location on another map is easily achieved when latitude and longitude are represented in a common way, or when the name of one location is either represented in a common way, such as both in a certain language, or able to be related via a thesaurus or the equivalent. It would not have made sense if every map in a collection were developed according to different forms of representation; the standardisation of representations enabled the accumulation of maps to form the universal map, or atlas. In the same way, the widespread mapping of accessible resources on the Web is achieved by the use of a common form of representation so that searches can be performed across collections of resources. Interoperability functions at four main levels: structure, syntax, semantics and systemic adoption (Nevile & Mason, 2005). (See ch...)

The AccessForAll team (the AfA team) worked to exploit the use of metadata in the discovery and construction of digital information in a way that could increase Web accessibility on a world wide scale. The outcome is a set of specifications (now forthcoming as standards) that can be used to enable the production of an atlas of accessible versions of information so that individual users everywhere can find something that will serve their purposes in a way that is independent of their choice of device, location, language and representational form. There are several ways in which this work needs to be followed by other work: to enable a similar selection of user interface components (see FLUID) and perhaps certification of organisations and systems that provide the new service, or at least those that enable it by providing useful metadata (see Concl ch.).

The work is considered successful because there is now a growing number of situations for which metadata is being planned as the management tool for descriptions of objects and services and of people's needs and preferences with respect to them, so that resources that are suitable can be discovered by users where they are well-described. In addition, resources should be able to be decomposed and re-formed using metadata to make them accessible to users with varying devices, location, languages and representation needs and preferences, and there has been significant if not yet widespread adoption of the method (by developers such as Angel technologies and SAKAI, Moodle, etc etc whom?). Such metadata can be used immediately to manage resources within a shared environment such as the original one established at the University of Toronto where the AccessForAll approach was first considered. But there is greater potential for it such as to use it in a distributed environment. Exactly how to do this is proving a challenge but it seems that the problem is so closely aligned to the problems being considered by W3C's working group developing POWDER (POWDER) that this problem will soon disappear (see ch ??).

The goal of the author's work was always to increase the accessibility of the Web. Accessibility is of concern because it ensures that those with disabilities, often using special devices, can access information. But their needs are equivalent to those of people with no disabilities of the conventional type but who suffer disability in their immediate circumstances (as explained in ch.....). Such (human-) constructed disabilities (see World Health Organisation definition of disability in ch...) are exemplified by the expectation that the same information should be available on a large screen for an audience, on a touch-screen at a local airport, on a home computer, on a laptop computer, on a PDA or on a telephone or invisibly available to a device that uses it to generate something for a user. If the metadata proposed can enable all such users to gain equal access to the same information, it will be enabling what is known as accessibility for all (see ch ... ).

If information is not accessible, metadata cannot make it so, but if it is accessible or there is some representation of the information contained in a given set ofcontent that can replace any inaccessible content, that accessible content might be made discoverable by the use of metadata. The idea is that without metadata, even where there is accessible information, it may not be discoverable by a user who has a need or preferences for it, and so what is available to the user may be inaccessible. If inaccessible content can, on the other hand, be augmented, transformed or replaced by information that is accessible, the original information is considered to be accessible.

Preliminary accessibility work was undertaken by the author to establish a clear image of current activity with respect to accessibility of Web resources. This entailed a translation of the best known specifications for accessibility, those developed by the community working with World Wide Web Consortium's Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI; see ch ...), into operational practices.

W3C/WAI Guidelines (WGAC, ATAG, UAAG, etc see ch..) contain the advice of many in a form that is, as best it can be, generic across technologies and future proof. It aims to provide criteria against which resources can be tested to determine if the maximum number of people, despite any disabilities they may have or any accessibility constraints they may reasonably be expected to suffer, can access the resource. (The short-comings of the WAI specifications are discussed in detail throughout the thesis, whereas they are written as operational in the section known as the Accessible Content Development section; Nevile1).

In the operational section, there was an attempt to make the reason for the specifications clear so that anyone using them would know what in fact they were aiming to achieve. It was hoped that not only would the section provide a sort of how-to approach based on the goals of a developer, but that developers would be able to make wise decisions about how to use the specifications. Although this approach might have proven useful in the end, it operated as a catalyst for thinking about other ways to increase the accessibility of the Web, given the dismal failure of the work to date. The attempt also failed because to be effective it would depend on a community of developers using it and adding to it. The site was never used in any big way but the approach has been very successfully implemented in the Web Standards Group of developers [WSG].

As is shown below, there was a sense of frustration developing with respect to accessibility. It might have been a simple case of the lows that inevitably follow the initial highs when a new technology is developed, but it was not going away. The complexity of Web encoding was increasing rapidly and the specifications were increasingly being shown to be wanting in various ways. What Web content authors chose to do was more often related to the use of the latest technological fad than increased control on content to make it more accessible and the software developers were not worrying about accessibility either.

In this context, it appeared as often as not to be a marketing issue as much as a technical one: people did not find it easy to follow the guidelines for accessibility of content [WCAG], if they did happen to know about them and want to follow them, but more and more they were finding that if they did succeed in following them, they were not seeing any particular advantages from having done so. In particular, the major browser developers were not complying with the guidelines for user agents [UAAG] and the major authoring tools did not conform to the guidelines for authoring tools [ATAG]. Only people who took extra care and worked at the encoding level could realistically expect to make accessible content. The common perception was that it was difficult, expensive, and most developers did not know how to do it anyway. Although there was, even then, the threat of anti-discrimination or other legal action, in fact these were not happening. In the US, the legislation that related to accommodations for people with disabilities in the Federal Government context was operating but on such a low level of what might be called 'accessibility' and in such limited circumstances that it too, was not offering much hope.

About this time, the author worked with established colleagues from the accessibility field, in the context of the IMS Global Project [IMS GLC] to write a set of accessibility guidelines for education. They were not supposed to replace the WCAG, but rather to be contextual, interpretive and easy for those in education who may not have a deep understanding of or interest in accessibility or content coding, or the time to study them despite the requirement in most places that they provide accessible content.

The frustration was beginning to take its toll. The author was finding work on metadata much more satisfying and effective, despite the continued effort with respect to accessibility. But one thing led to another and soon the author was working with colleagues from the accessibility area who were beginning to think about using metadata to find a more effective way to tackle the accessibility problem.

In 2001, the author engaged directly with the relevant work of the Adaptive Technology Resource Center [ATRC] at the University of Toronto where, within a university, work had been underway to produce a prototype system that would match resources to users' needs. This work was demonstrated in the system now known as The Inclusive Learning Exchange [TILE]. The ATRC specialises in accessibility so that it was able to develop a system for combining accessible content into customised packages for its clients. Taking this idea and making it a generalised approach for education (under the umbrella of the IMS Global Learning Consortium [IMS GLC], was the first task. The WGBH National Center for Accessible Media [WGBH/NCAM] SALT project sponsored this work within IMS. Then it was taken to the rest of the world as a fast-tracked development of an ISO JTC1 SC36 Learning, Education and Training Standard [SC36]. This was a substantial task and one that engaged the author (as co-editor) and others for several years.

The author had already established the international Dublin Core Accessibility Working Group [DCMI Access] to examine the use of metadata in the accessibility field and was aware of the problems associated with trying to use Dublin Core metadata as it was, in this new context. The context was new in that it was not just a purpose beyond the more common one of resource discovery, for which DC metadata was usually used, but because it was to achieve a political goal as well, the increased accessibility of the Web. Using metadata for such a purpose involved a new way of thinking about DC metadata and particularly a major challenge when metadata was to be used to describe the attributes of a fictional or abstract resource (an unidentified, metaphoric person (Nevile, 2005b). (This problem is considered further in ch ...??) At that time, Dublin Core metadata was also proving problematic. Although the metadata model had been designed to be simple so that it could easily be standardised, users had stretched it out of context and found it wanting and they were making slight differences in how they were using it so that the desired interoperability was not always available (Currie et al, 2002).

The early research questions within the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative Accessibility Working Group [DCMI Access] that finally lead to the metadata work as finally determined, included:

At this early stage, the idea was to find a simple way of describing resources so that users could find and use what they needed. It assumed that the WCAG guidelines would provide the best measure of this quality, but sought greater detail than a simple pass or failure of the tests those specifications could offer. In 1998, the US Federal Government introduced legislation [s.508] that required all federally funded bodies publishing on the Web to ensure their resources were compliant with a subset of the WCAG for content accessibility. This legislation included some requirements from the Authoring Tools Accessibility Guidelines (ATAG; see also ch ..). In 2004-6, some in Europe have endeavoured to create what is known as a quality mark to assert an absolute measure of accessibility of a resource (CWA 15554), and the author has been one of many strongly opposing this activity for a number of reasons.

In particular, the author and the other participants involved in the IMS work decided to broaden the metadata work from the beginning, ensuring that it was done in an open environment and that the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative Working Group [DCMI Access] members, and others, were able to participate. The author was also involved in European Commission activities to do with the development of metadata and so brought the work into that realm as part of work done in the European Committee for Standardization Meta-Data (Dublin Core) Workshop [MMI-DC]. By now, three otherwise distinct communities were interacting:

There was also the involvement of a range of sectors:

Local, national and international issues were becoming relevant. Local developers would need to be able to work with the proposed metadata and so they were concerned to ensure their tools would handle the proposed metadata; national bodies were concerned that their national standards would be supported, and internationally there were issues to do with multi-culturality (actually an issue inside some countries as well).

In addition, by involving the Dublin Core metadata community, the problem of interoperability was increased: Dublin Core metadata is based on a very different model from IMS metadata (derived from IEEE/LOM. (See ch) and so a number of problems were introduced into the scene. The aim of working with the DC community was to take advantage of the widespread use of DC metadata in domains other than education, but for resources that were often used in educational settings. In particular, government resources were known to be described more often using DC metadata than other metadata, so they would become part of the system without too much trouble if the solution was suitable. It was assumed that working with DC-style or DC-interoperable metadata would also render the resources more useful as occupants of the Web 2.0 world, as they would be tagged in ways that were more consistent and therefore more interoperable with other Web 2.0 resources, including with any Web services that might be involved.

The work was also broadened in that it was developed for a distributed environment, where there would not always be accessible content available, or, at least where it might require discovery of that content, for substitution or augmentation of existing resources. This introduced a new set of problems. The original resource might have been discovered by a search but how would it come about that a replacement resource would be found unless the search was refined to ensure that what was discovered was accessible to the user involved? (The author collaborated with researchers in Japan who explored the use of a FRBR model of metadata to trace back from a resource to its source in order to find another manifestation of it that could be used to provide additional accessibility (Morozumi et al, 2006).

All this work was supported by careful review of the literature and practices of others with respect to the issue.

A draft roadmap of related specification and standards activities was developed in early 2003 (Nevile7). There is now a formal W3C roadmap document [W3C Roadmap]. In order to ensure maximum effect from the work being undertaken, it was essential to make sure it would not only be interoperable with other work, but that it could take advantage of that, where possible. The main community working on related specifications and standards was the W3C WAI. The author had worked with this community and been involved, and continues to be involved on a spasmodic basis, particularly in the development of the Authoring Tools Accessibility Guidelines [ATAG]. She also worked closely with the INCITS V2 community as they developed the Universal Console specifications [INCITS V2] and ISO standard [JTC1 SC35 WG8], the Australian Government Locator Standard [AGLS]. Others involved in the work included participants in the CEN ISSS Learning Technologies Workshop [CEN/ISSS LT]. (A brief introduction to the most relevant organisations and standards bodies is available below.)

In 2004, Tim O'Reilly coined a term that has become a catch-cry far and wide. Later he said of it (2005):

The concept of "Web 2.0" began with a conference brainstorming session between O'Reilly and MediaLive International. Dale Dougherty, web pioneer and O'Reilly VP, noted that far from having "crashed", the web was more important than ever, with exciting new applications and sites popping up with surprising regularity. What's more, the companies that had survived the collapse seemed to have some things in common. Could it be that the dot-com collapse marked some kind of turning point for the web, such that a call to action such as "Web 2.0" might make sense? We agreed that it did, and so the Web 2.0 Conference was born.

In the year and a half since, the term "Web 2.0" has clearly taken hold, with more than 9.5 million citations in Google. But there's still a huge amount of disagreement about just what Web 2.0 means, with some people decrying it as a meaningless marketing buzzword, and others accepting it as the new conventional wisdom.

A significant aspect of the Web as envisioned is that it is a platform:

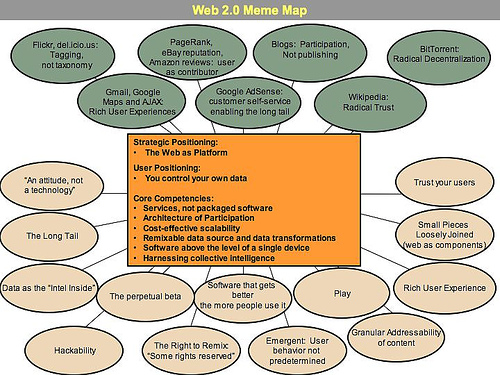

Like many important concepts, Web 2.0 doesn't have a hard boundary, but rather, a gravitational core. You can visualize Web 2.0 as a set of principles and practices that tie together a veritable solar system of sites that demonstrate some or all of those principles, at a varying distance from that core.

O'Reilly offered the following diagram from a brain-storming session to help others visualize this 'new' Web:

Many of the features depicted in this image are deployed in the new metadata for accessibility work. The following, in particular, fit into this category:

In November 2005, Dan Saffer described Web 2.0:

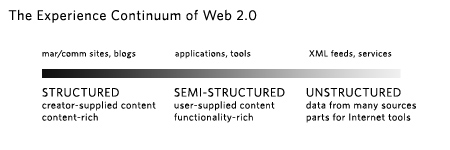

On the conservative side of this experience continuum, we'll still have familiar Websites, like blogs, homepages, marketing and communication sites, the big content providers (in one form or another), search engines, and so on. These are structured experiences. Their form and content are determined mainly by their designers and creators.

In the middle of the continuum, we'll have rich, desktop-like applications that have migrated to the Web, thanks to Ajax, Flex, Flash, Laszlo, and whatever else comes along. These will be traditional desktop applications like word processing, spreadsheets, and email. But the more interesting will be Internet-native, those built to take advantage of the strengths of the Internet: collective actions and data (e.g. Amazon's "People who bought this also bought..."), social communities across wide distances (Yahoo Groups), aggregation of many sources of data, near real-time access to timely data (stock quotes, news), and easy publishing of content from one to many (blogs, Flickr).

The experiences here in the middle of the continuum are semi-structured in that they specify the types of experiences you can have with them, but users supply the content (such as it is).

On the far side of the continuum are the unstructured experiences: a glut of new services, many of which won't have Websites to visit at all. We'll see loose collections of application parts, content, and data that don't exist anywhere really, yet can be located, used, reused, fixed, and remixed.

The content you'll search for and use might reside on an individual computer, a mobile phone, even traffic sensors along a remote highway. But you probably won't need to know where these loose bits live; your tools will know.

These unstructured bits won't be useful without the tools and the knowledge necessary to make sense of them, sort of how an HTML file doesn't make much sense without a browser to view it. Indeed, many of them will be inaccessible or hidden if you don't have the right tools. (Saffer, 2005)

As Saffer says,

There's been a lot of talk about the technology of Web 2.0, but only a little about the impact these technologies will have on user experience. Everyone wants to tell you what Web 2.0 means, but how will it feel? What will it be like for users?

The framwork bring developed in this dissertation should give a sense of the changes at least in the realm of accessibility. One significant change being, hopefully, that what is done will make the Web more accessible to everyone, not that there will need to be special activities for some people.

These comments are made at a time when there is already talk of Web 3.0. This idea of versions of the Web is clearly abhorrent to some, as its continuous evolution is considered by them to be one of its virtues (Borland, 2007), but the significance of the changes in the Web are not denied. If Web 3.0 represents anything, according to Borland:

Web 1.0 refers to the first generation of the commercial Internet, dominated by content that was only marginally interactive. Web 2.0, characterized by features such as tagging, social networks, and user- created taxonomies of content called "folksonomies," added a new layer of interactivity, represented by sites such as Flickr, Del.icio.us, and Wikipedia.

Analysts, researchers, and pundits have subsequently argued over what, if anything, would deserve to be called "3.0." Definitions have ranged from widespread mobile broadband access to a Web full of on-demand software services. A much-read article in the New York Times last November clarified the debate, however. In it, John Markoff defined Web 3.0 as a set of technologies that offer efficient new ways to help computers organize and draw conclusions from online data, and that definition has since dominated discussions at conferences, on blogs, and among entrepreneurs. (Borland, 2007, page 1)

While there are many organisations related to accessibility, too many to even name, there are some organisations that have played a significant role in shaping the Web since its inception. Some of these will be identified here as they usually also provide many online resources and any understanding of the 'literature' of accessibility of the Web or metadata relating to it necessarily relies on familiarity with the work of these organisations.

W3C's approach has evolved over time but it is currently understood as promoting 'universal design'. This idea was fundamental to WCAG 1.0 and is maintained for the forthcoming (WCAG 2.0) guidelines for the creation of content for the Web. WCAG is complemented by guidelines for authoring tools that reinforce the principles in the content guidelines and W3C also offers guidelines for browser developers. Significantly, the guidelines are also implemented by W3C in its own work via the Protocols and Formats Working Group who monitor all W3C developments from an accessibility perspective.

W3C entered the accessibility field at the instigation of its director and especially the W3C lead for Society and Technology at the time, Professor James Miller, shortly after the Web started to take a significant place in the information world. W3C established a new activity known as the Web Accessibility initiative with funding from international sources. From the beginning, although W3C is essentially a members' consortium, in the case of the WAI, all activities are undertaken openly (all mailing lists etc are open to the public all the time) and experts depend upon input from many sources for their work.

The W3C/WAI activity has done more than develop standards over the years through its fairly aggressive outreach program. It publishes a range of materials that aim to help those concerned with accessibility to work on accessibility in their context.

The Trace Research & Development Center is a part of the College of Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Founded in 1971, Trace has been a pioneer in the field of technology and disability.

Trace Center Mission Statement:

To prevent the barriers and capitalize on the opportunities presented by current and emerging information and telecommunication technologies, in order to create a world that is as accessible and usable as possible for as many people as possible. ...

Trace developed the first set of accessibility guidelines for Web content, as well as the Unified Web Access Guidelines, which became the basis for the World Wide Web Consortium's Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 1.0 [TRACE].

Wendy Chisholm, who originally worked at TRACE was, for many years, a leading staff member of WAI and author of a number of the accessibility guidelines and other documents.

The Adaptive Technology Resource Centre is at the University of Toronto. It advances information technology that is accessible to all through research, development, education, proactive design consultation and direct service. The Director of ATRC, Professor Jutta Treviranus, has been significant in the standards work in many fora and the group has contributed the main work on the ATAG. They are also largely responsible for initiating the work for the AccessForAll approach to accessibility and the technical development associated with it.

The Carl and Ruth Shapiro Family National Center for Accessible Media is part of the WGBH, one of the bigger public broadcast media companies in the USA. Henry Becton, Jr., President of WGBH, is quoted on the WGBH Web site as saying that:

WGBH productions are seen and heard across the United States and Canada. In fact, we produce more of the PBS prime-time and Web lineup than any other station. Home video and podcasts, teaching tools for schools and home-schooling, services for people with hearing or vision impairments ... we're always looking for new ways to serve you! (WGBH About, 2007)

With respect to people with disabilities, the site offers the following:

People who are deaf, hard-of-hearing, blind, or visually impaired like to watch television as much as anyone else. It just wasn't all that useful for them ... until WGBH invented TV captioning and video descriptions.

Public television was first to open these doors. WGBH is working to bring media access to all of television, as well as to the Web, movie theaters, and more (WGBH Access, 2007).

NCAM is a major vehicle for these activities within the media context and its Research Director, Madeleine Rothberg, has been a significant researcher and author in the work that supports AccessForAll in a range of such contexts.

In addition to organisations that have been involved in the research and development that have led to the AccessForAll approach and standards, there have been the standards bodies themselves that have published standards but also initiated work that has made the standards' development possible. In many cases, standards are determined by 'standards' bodies which are, as in the case of the International Organisation for Standardization [ISO], federations of bodies that ultimately have the power to make laws with respect to the specifications.

W3C's role in the standards world is often described as different from, say, the role of ISO because of the structure of the organisation and also the processes used to develop specifications for recommendation (de facto standards). W3C membership is open to any organisation and tiered so that larger more financial organisations contribute a lot more funding than smaller or not-for-profit ones. The work processes are defined by the W3C so that working groups are open and consult widely and prepare documents which are voted on by members and then recommended, or otherwise, by the Director of the W3C, Sir Tim Berners-Lee. They are published as recommendations but usually referred to as standards and certainly, in the case of the accessibility guidelines, are de facto standards.

ISO collaborates with its partners, the International Electrotechnical Commission [IEC] and the International Telecommunication Union [ITU-T], particularly in the field of information and communication technology international standardization.

ISO makes clear on their Web site, that it is

a global network that identifies what International Standards are required by business, government and society, develops them in partnership with the sectors that will put them to use, adopts them by transparent procedures based on national input and delivers them to be implemented worldwide (ISO in brief, 2006).

ISO federates 157 national standards bodies from around the world. ISO members appoint national delegations to standards committees. In all, there are some 50,000 experts contributing annually to the work of the Organization. When ISO International Standards are published, they are available to be adopted as national standards by ISO members and translated.

The Joint Technical Committee 1 of ISO is for standardization in the field of information technology. At the beginning of April 2007, it had 2068 published ISO standards related to the TC and its SCs; 2068; 538 published ISO standards under its direct responsibility; 31 participating countries; 44 observer countries; at least 14 other ISO and IEC committees and at least 22 international organizations in liaison (JTC1, 2007). JTC1 SC36 WG7 is the working group for Culture, language and human-functioning activities within the Sub-Committee 36 for IT for Learning Education and Training. it is this working group that has developed the AccessForAll All standards for ISO. Co-editors for these standards come from Australia (Liddy Nevile), Canada (Jutta Treviranus) and the United Kingdom (Andy Heath), but there have been major contributions from others in the form of reviews, suggestions, and discussion and support.

The IMS Global Learning Consortium [IMS] describes itself as having more than 50 Contributing Members and affiliates from every sector of the global learning community. They include hardware and software vendors, educational institutions, publishers, government agencies, systems integrators, multimedia content providers, and other consortia. IMS claims to provide "a neutral forum in which members work together to advocate the use of technology to support and transform education and learning" (IMS, 2007).

A joint project between WGBH/NCAM and IMS initiated the work on AccessForAll with a Specifications for Accessible Learning Technologies Grant in December 2000. Anastasia Cheetham, Andy Heath, Jutta Treviranus, Liddy Nevile, Madeleine Rothberg, Martyn Cooper and David Wienkauf were particularly significant in this work.

The Web site describes the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative as

an open organization engaged in the development of interoperable online metadata standards that support a broad range of purposes and business models. DCMI's activities include work on architecture and modeling, discussions and collaborative work in DCMI Communities and DCMI Task Groups, annual conferences and workshops, standards liaison, and educational efforts to promote widespread acceptance of metadata standards and practices (DCMI, 2007).

The DCMI Accessibility Community has been working formally on Dublin Core metadata for accessibility purposes since 2001. While the early work focused on how metadata might be used to make explicit the characteristics of resources as they related to the W3C WCAG, this goal has been realised in the AccessForAll work. The DCMI Accessibility Community has been working in close collaboration with the IMS and ISO efforts but it has engaged the metadata community, and therefore those working primarily in a wider context than education, especially including government and libraries.

The European Committee for Standardization, was founded in 1961 by the national standards bodies in the European Economic Community and European Free Trade Association countries. CEN is a forum for the development of voluntary technical standards to promote free trade, the safety of workers and consumers, interoperability of networks, environmental protection, exploitation of research and development programmes, and public procurement (CEN, 2007).

A number of CEN committees have been involved in the development of AccessForAll, either in the form of contributed funding as for the MMI-DC, or in their independent review of the development of AccessForAll and how it will work in their context if it is adopted by the other standards bodies. Significant in this work have been Andy heath, Liddy Nevile, Martyn Cooper and Martin Ford who have all worked on CEN projects in recent years. the context for this work has included but not been limited to education.

There are a number of other standards bodies or regional associations that have considered the work in depth and contributed in some way. In fact, in early 2007, IMS versions of the specifications had been downloaded 28,082 times and the related guidelines more than 176,505 times. (Rothberg, 2007) CanCore has published the CanCore Guidelines for the "Access for All" Digital Resource Description Metadata Elements (Friesen, 2006) following an interview with Jutta Treviranus in which she discusses the specifications (Friesen, 2005).

The Centre for Educational Technology and Interoperability Standards [CETIS] in the UK provides a national research and development service to UK Higher and Post-16 Education sectors, funded by the Joint Information Systems Committee. CETIS has published some summary documents about the IMS AccMD, IMS AccLIP and IMS Guidelines.

The framework is developed to help understand why and how the metadata work was done in order to assess its validity and likely chances of success in the long-term. The work seemed like 'a good idea at the time' and was modeled on a system that was working in a closed environment (TILE at the University of Toronto), but for larger systems and others wanting to be sure it is the right approach and its limits and benefits, there was nothing available.

The collaborative work was undertaken essentially by a small team who worked very closely together for a number of years. Together they developed some specifications that had to be evaluated by many others throughout the process. At times, the team or various combinations of members of the team wrote about the work, justifying it in various contexts and for a number of audiences. The author of this dissertation, uniquely, has worked through all the issues to develop a framework that will enable others to evaluate the potential of the work.

The dissertation provides an analysis of what is understood as accessibility and does the same for metadata; describes the context and scope of the work; explains the problem with current approaches designed to solve the problem; describes the metadata approach and the standards and specifications developed to realise this approach, and finally provides a demonstration of the difference that can be made with the metadata. The author has documented as no others yet have, how this work forms a new framework for accessibility and provides a way forward towards a more accessible information future for all.

The range of users catered for by the new framework is broad. In most work in the field of accessibility, the efforts have been driven by the needs of those with disabilities and, in many cases, anti-discrimination legislation to protect their rights. In this case, AccessForAll has been defined much more broadly and aims to provide for all who have medical and constructed disabilities. It can be thought of as inclusive rather than anti-discriminatory with respect to people with disabilities. As this is a major part of the work, and differentiates it from other work, it is described with precision to establish exactly what is meant by AccessForAll, who is affected, how many users are involved, and what their problems and needs are.

The framework provides a structure into which more accessibility activities can be fitted; it relates its semantics to existing semantics, it anticipates the use of standard syntax but does not restrict the syntax to already used languages, and it has been developed with wide consultation to ensure community support. These are the four aspects of interoperability and they are given priority so that collaboration and cooperation can follow to provide the network effect. The framework is also developed so that future work can be done more easily. Such work is anticipated in areas such as the recording of the accessibility features of places and events for matching to recognised accessibility needs and preferences of people, the FLUID work with interchangeable, user-selected user interface components, and more.

A detailed curriculum vitae for the author within the field of accessibility is available in Appendix 1.