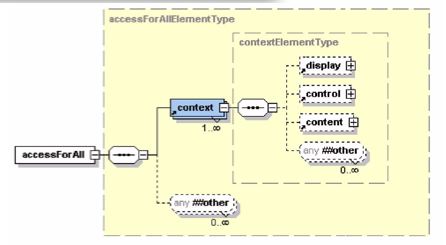

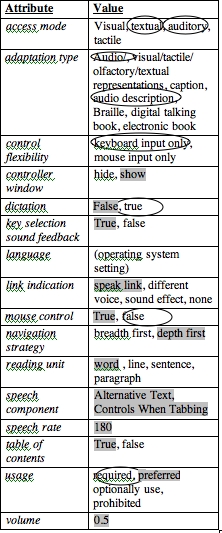

Fig. 1: AccessForAll structure and vocabulary (image from AccessForAll Specifications, [IMS Accessibility].

Site Navigation

Contents of Thesis ack'ments - Preamble - Introduction -Accessibility - W3C/WAI - LitReview - Metadata - Accessibility Metadata - PNP - DRD - Matching - UI profiles - Interoperability - Framework - Implementation - Conclusion - References - Appendix 1 - Appendix 2 - Appendix 3 - Appendix 4 - Appendix 5 - Appendix 6 - Appendix 7

Given that universal design alone is not able to cater for the needs and preferences of all users, even when the principles embodied in the WCAG specifications are complied with, and that is not often as has been shown, it was timely when a complementary approach was suggested by the ATRC at the University of Toronto. Already there was a prototype system operating that could match resource components to user-determined requirements (TILE) when the work was shared with those at the IMS Global Learning Consortium. At this time, the author was already working for IMS Australia (Australian Department of Education, Science and Technology) with the IMS GLC. The first task had been a set of guidelines for educators about accessibility (Barstow and Rothberg, 2002). These guidelines were developed at about the same time as the author's Accessible Content Development section (ref), and both showed the inadequacy of the then current work. The adoption of a complementary approach that would take into account the needs and preferences of individual users was attractive to the author and likely to lead to the sort of outcomes that would satisfy the author.

In fact, the AccessForAll approach was a significant development and only the beginning of a chain of developments that has most recently led to the FLUID Project, a major user-interface architecture re-design project directed from the ATRC.

In 2005, the author wrote a paper for the Dublin Core Conference (Nevile, 2005b). The first part of this chapter is a modified version of that paper. The later part explains a little about the process of developing the profiles and the issues to do with making them interoperable. It presents the case for a private (anonymous) personal profile of accessibility needs and preferences expressed in a Dublin Core format. It introduces the idea that this profile, identified only by a URI, is motivated by a desired relationship between a user and a resource or service. It assumes a new Dublin Core term DC:Adaptability and argues that, without any reference to disabilities, personal needs and preferences, including those symptomatic of common physical and cognitive disabilities, context or location, can be described in a common vocabulary to be matched by resource and service capabilities.

The European view of disability, adopting the words of the World Health Organisation, is broad and states significantly that disability:

is not entirely an attribute of an individual, but rather a complex social and environmental construct largely imposed by societal attitudes and the limitations of the human-made environment. Consequently, any process of amelioration and inclusion requires social action, and it is the collective responsibility of society at large to make the environmental and attitudinal changes necessary for their full participation in all areas of life (European Commission Report Number DG INFSO/B2 COCOMO4 – p. 14.).

It is inappropriate and inefficient, when such a view prevails, to continue to describe people by what are seen sometimes as their disabilities: everyone, at some time or another, is disabled by the circumstances in which they find themselves and most people, as they age, will experience disabilities more often. Most people will find their disabilities vary according to the circumstances in which they are operating. Disability, in this sense, is a description of a poor relationship between a person and their immediate operational requirements.

Similarly, it is inappropriate and inaccurate to attribute descriptions of disabilities, which are descriptions of relationships, to named people. At the same time, it is efficient to recognize that many relationships are similar and that when involved in a user-resource relationship, many people will want to use the same description of that relationship. For instance, many blind people trying to access a Web page with images will want to use similar profiles of non-visual relationships between a user and a resource.

The existence of a machine-readable profile of a disability relationship can be used, by suitable applications, to match users with resources and services they can use. This process involves a description of a user's immediate needs and preferences being matched with a description of the components of a resource or service until there is no disability. This may involve the replacement, augmentation or transformation of components of the resource or service, such as changes of sensory modality. The user's descriptions of their needs and preferences, often called their profiles, will be used according to the context or circumstances and may differ according to the occasion. For convenience, a user will want to store and refer to such profiles rather than to create them afresh every time one is required. In some cases, they will depend upon profiles created for them by others, and in such cases may be especially dependent on their being stored and available at all times.

One interesting example of how disabilities change occurs when users move from one location to another, especially in circumstances where resources and services are location-based. In such a situation, an English-speaking person moving through Asia will suffer a range of disabilities as the resources and services they want are delivered in local languages and use local cultural signals they do not understand.

An accessibility profile for use by a blind person attempting to read a newspaper online will be very similar to that for a person driving a car wanting to access Google News: both users will want vision-free access to the resource. Both users will need alternatives to visual content contained in the primary resource they seek and both will want to control their access to that resource using non-visual techniques. A simple description of the relationship they seek with the resource will be of a non-visual relationship. The characteristics of this relationship, the user's needs and preferences profile, should be simply expressed in machine-readable form and available to any resource publisher. It can be identified by its URI and does not need to contain any information about any individual or community of people. It is, in fact, a description of functional requirements and could be know as a ‘non-visual functional profile'.

A more complicated example occurs where, for whatever reason, there is a need for a visual relationship but the objects being viewed need to be larger than they might be when used on a stand-alone desktop computer. Such a case occurs frequently when resources are displayed on a large screen before a large audience. For this to be an accessible relationship, it does not need to be non-visual but there are some qualifications to be made to the visual qualities: the text and images need to be enlarged. Exactly how large the text should be will usually be decided by the author in a situation where the details of the relationship are well-known, as for the large audience, but should always be available for customisation where individuals may have special needs.

Flexibility of the kind required in this case means there needs to be a common way of describing the range of sizes of text and images so that the correct accessible relationship can be indicated by the user. Responses to the description of the relationship in such a case may depend upon the transformability of the resource components: scalar vector images will be easily transformed to suit such requirements and text that is to be presented according to cascading styles should be suitably transformable but, if it contains tables, there will be more complicated considerations.

In some cases, it is not a transformation of available components that is required so much as their replacement or augmentation. Such a case exists where a non-auditory relationship is required with, for example, a movie. Then, a text transcription of the background sounds might need to be supplied with captions for all speech. These may all need to be synchronized with the visual content. Where the only problem with the aural content is likely to be the choice of language, captions might be required but the background sounds will not be a problem.

The provision of resources and services that ensure the correct accessible relationship for a user depends upon the existence of many components all with special accessibility characteristics. Captions for films are usually made by organizations known as caption houses: caption houses specialize in making captions but not films. Signing for people who use sign languages is usually done by specialists in that field; videos of signing that might be needed to complete an accessible relationship are likely to come from a source other than the original publisher of the resource.

In other words, the components that may be required to complete an accessible relationship with a resource or service are often distributed and may be the result of cumulative authoring. All that is necessary is that the components are available just-in-time for delivery to the user. Very often, as is obvious from the examples already given, they may be combined in different ways for different user/resource relationships. This means it is most convenient to not fix them to a particular relationship with any one resource, but to maintain them separately and make available the necessary metadata for them to be fetched when needed. The same metadata can be used to identify a need for more components in anticipation of a demand for them.

The definition of accessibility implied here is that the relationship between the user and the resource is one that enables the user to make sensory and cognitive contact with the content of the resource. This is expected to occur at the time of accessing the resource or, in other words, to be achieved just-in-time. This is the definition being advocated as the AccessForAll definition of accessibility.

In addition to the availability of the necessary components to satisfy the relationship required by the user, there is a requirement for the metadata that will be used to arrange the final composition of the resource. There is also, of course, a need for a way of communicating the requirements, or the metadata. The vocabularies and common specifications for their description are the topic of this chapter. W3C was working on similar issues in their Device Independent Working Group and their focus is on what they call the Composite Capabilities and Personal Preferences specifications [CCPP].

There are three modalities universally recognized as relevant to the human-computer relationship: visual, auditory and tactile. (Initially smell was not considered but in the end olfactory was included.) There are many possible variations of the modalities and their roles can be important: auditory input and output are not necessarily related to a user rather than their context. In a library, one may be able to listen with headphones but asked not to use voice input; in a car, general auditory output may be acceptable and voice input may be essential. While input and output are, in some cases, useful distinctions to make, in the case of accessibility it makes more sense to talk about display characteristics, control characteristics and content characteristics.

For people who use adaptive technologies with special settings, describing their control needs and preferences may mean providing information about the settings for their personal adaptive technology, especially when that requires something like an on-screen keyboard to be activated by a head-pointer. In the case of an on-screen keyboard being used, the display characteristics of the resource also will need to be adapted to allow for the loss of screen space for display purposes. In addition, there may be requirements for other display characteristics, and there may be separate needs for content adjustment. Particularly for people for whom settings are crucial to their engagement with resources, needs and preferences are required. If a need cannot be fulfilled, their preference for what to compromise can make all the difference. For others, if flexibility is possible, it can mean greater satisfaction.

As, in fact, the many requirements can conflict, determining a structure for their representation that allows for them to be described fully and unambiguously is essential. For this reason, descriptions of needs and preferences for display, control and content characteristics need to be separated. The needs and preferences need to be easily describable, so it is essential that if there are no special needs, nothing needs to be described, but that when there is a need, there is a hierarchy of details that are easily understood and useful.

In addition to the three categories described and their details, there is an over-riding quality that is essential in the human-computer context. Usability is not a technical quality but it can be the most significant quality when user resource interactions are required. It is not included as a technical characteristic of AccessForAll but is assumed to be contemporaneously considered.

Fig. 1: AccessForAll structure

and vocabulary

(image from AccessForAll

Specifications,

[IMS

Accessibility].

Where there can be no effective visual relationship with resources and services, all visual displays need to be presented in some other modality. Often the choice is for auditory presentation of the visual content but it may be for tactile displays such as Braille or other tactile forms. Where the adaptive technology does not change the modality but changes the characteristics of the display, as in the case where screen-enhancing software is being used, the requirements for the desired display may involve object sizes, colour, or placement on the screen. The requirements can be very detailed and vary depending on the circumstances. Changes in the modality of content, as occur when a screen reader renders visual content (text) as auditory content, may depend upon it being possible to transform the content in this way. This in turn will depend upon the form of the original content: it can be transformed easily unless there is formatting, for example, that interferes with the process. The ‘transformability' of the text will need to be described if it is relevant to the user's relationship with the text.

6.2.1 Display Preference Set

Attribute

Allowed Occurrences

Datatype

screen reader preference set

Zero or one per Display Preference Set

Screen_Reader_Preference_Set

screen enhancement preference set

Zero or one per Display Preference Set

Screen_Enhancement_Preference_Set

etc

etc

etc

6.2.2 Screen reader Preference Set

usage

Zero or one per Screen Reader Preference Set

Usage_Vocabulary

screen reader generic preference set

Zero or one per Screen Reader Preference Set

Screen_Reader_Generic_Preference_Set

application preference set

Zero or one per Screen Reader Preference Set

Application_Preference_Set

and

6.2.9 Screen Enhancement Generic Preference Set

font face preference set

Zero or one per Screen Enhancement Generic Preference Set

Font_Face

font size preference

Zero or one per Screen Enhancement Generic Preference Set

Positive integer

foreground color preference

Zero or one per Screen Enhancement Generic Preference Set

Color

background color preference

Zero or one per Screen Enhancement Generic Preference Set

Color

etc

etc

Etc….

Fig. 2 Extracts from the “Individualized Adaptability and Accessibility in E-learning, Education and Training

Part 2: AccessForAll Personal Needs and Preferences Statement”, ISO/IEC JTC1 SC 36/WG 7 draft (http://jtc1sc36.org/doc/36N1025.pdf

Not all users control their systems using the typical mouse and keyboard combination. In some cases, they use assistive technologies that effectively replace these devices without any adjustment but in others they use technologies that require special configuration. An on-screen keyboard will use screen space that will have to be denied to the resource or service so that any resource or service that cannot accommodate this loss of screen space, for example because it demands a full-screen display for all controls to be available, will not be suitable for use in some circumstances.

It is necessary to be able to capture what is necessary with proprietary devices and systems and also what is generic to types of systems and devices. It is also necessary to be aware of possible developments and so there is room for extensions. A typical example of the definition of these needs is as shown:

3.2.41

text reading highlight generic preference set

a collection of data elements that states a user's preferences regarding how to configure a text

reading and highlighting system that are common to all text readers/highlighters, regardless of vendor

3.2.42

text reading highlight preference set

a collection of data elements that states a user's preferences regarding how to configure a text

reading and highlighting system (http://jtc1sc36.org/doc/36N1025.pdf)

These definitions have been represented in a structured hierarchy so that it is easy for users or their assistants to provide only as much detail as is necessary. Nevertheless, due to the complexity of dealing with the multitude of possible needs, the vocabulary is very large (http://jtc1sc36.org/doc/36N1025.pdf).

The relationship between a user and a resource or service will also be accessible only if the content is perceptible by the user. Perception in this sense includes the case where a dyslexic person needs more than the usual image-based content because they cannot process a text-heavy resource; while a person with neurological damage, such as a stroke victim, may not manage a screen that is too ‘busy', or a blind person is working with an explanation that is based on an example that is useful only to people with vision. It is often the case that the original content has to be supplemented, perhaps with the availability of a dictionary or captions, or replaced by different content that achieves the same outcome but in a different way. Information about the resource that indicates that it contains such alternative content, or the location of such content that is available externally, is needed to determine if the user will be able to form an accessible relationship with it in terms of perception.

The original IMS GLC approach was to add the AccessForAll element into the established hierarchy of the IMS Learning Object Model.

Whereas the DC model provides several ways in which a DC metadata set can be extended, the LOM requires the extensions to be determined and so it was necessary for any LOM extension to be anticipated:

In particular, most elements have <application> and <param> elements that allow additional parameters to be defined for a particular accessibility application. In addition, the binding provides for arbitrary extensions. See the Binding Guide document for more details. In general, these extension methods are provided as placeholders for future revisions of this specification. Both the <display> and <control> elements provide for sub-elements named <futureTechnology> which are intended to allow new technology approaches to be included. (Jackl, 2003, Sec.4.1 Extensibility Statement)

from

(Jackl,

2003, Sec. 2.2 Changes to the <accessibility> Element

Formatting).

Not only was the model heirarchical (see Fig ???) but the thinking was. If one has thought for a long time with a particular model, and is obliged to implement systems in a hierarchical environment, it is very difficult to think otherwise. This problem was acute for some time with the group working on AfA metadata but it led to very lively, activity as the participants struggled to make the AfA work as interoperable as they could, trying to accommodate both the hierarchical LOM model and the 'flat' DC model. The challenge was insurmountable but it led to very thorough efforts and what all parties in the end agreed was at least an elegant solution. There was considerable confidence that it could, indeed, be implemented in both LOM and DC without loss, even if this did depend on a cross-walk from one to the other.

The relationship between a user and a resource is defined as accessible when the characteristics of the resource or service, as delivered, match the user's control, display and content (perceptual) needs and preferences. The resource or services' characteristics can be fully described for this purpose using the proposed Dublin Core Adaptability element or other metadata specifications. These descriptions need to be available.

Web-4-All uses a smart card that carries the necessary information about a user's needs and preferences for settings for adaptive devices and software available within a device. The computer establishes the correct control relationship between the software and the user and resets the computer when the user's card is withdrawn.

It is the author's contention that if the resource or service's capacity to adapt to different user needs and preferences is described in a Dublin Core element, the individual user's needs and preferences also should be described in Dublin Core format. So we imagine a resource that contains information about a user's needs and preferences; what in some contexts is being called the user's Personal Needs and Preferences (PNP). Then we imagine a metadata record of that resource. It is possible, of course, that the metadata record is embedded in the resource.

3.6 Fig. 2 Diagram showing cycle of searches and role of AccessForAll server

It is obvious from the discussion above that in order to match a resource or service to a user to achieve accessibility, there is no need to identify the user. All that is required is machine-readable information about their needs and preferences.

The Dublin Core practice of creating a set of elements for use where those elements come from already established element sets is known as the process of creating an ‘application profile' (see ch ???). As, at the time, it was not clear exactly how DC comformant application profiles were to be defined, because the DC Abstract model was not completely defined, as explained above (ch ??), it was very difficult to define an application profile for AccessForAll user needs and preferences. Possibly a large part of the problem was that for a long time the DC experts were not convinced that it was really likely to happen, and would not be used, and was not a high priority, in fact. Perhaps it was because the metadata profile was to be a profile of a set of metadata and that introduced all sorts of problems that were not easily dealt with in standard DC metadata, especially as it is not hierarchical. Whatever the reason, it proved a tortuous process that lasted a few years.

An application profile for user accessibility needs and preferences that satisfies the requirements needs to contain one vital element; the DC:identity of the information (resource) expressed as a URI. This URI must, therefore, point to the user's accessibility needs and preferences information which should be in a machine-readable form. Users may like to think of profiles as being associated with certain contexts, for instance the lecture theatre version, or the JAWS lap-top version, and in such a case the profile could be named. So we could find DC:title being used for this. The application profile may contain more DC elements, such as DC:subject, DC:description, DC:creator, etc. None of these need identify the user for or by whom the AccessForAll information will be used. They may, on the other hand, clarify who could take advantage of the profile: for instance, all students in a lecture theatre will probably share the need for large print on the overhead screen. This could be explained in a DC:description element. It may be of interest to know who developed the user needs and preferences profile, so DC:creator could be used to indicate this. The date of a profile might be significant when new versions of adaptive software are released so DC:date may be useful.

In general, a profile will be for a single person, sometimes from within a class of people, such as someone with Jaws with the default settings, for instance. The profile could, however, cater for a combination of users with a combination of needs and preferences, even asking for redundant components so that everyone in the group has what they need. It is very common for a person with a disability to be working with someon who has different needs. In fact, some users' needs include a person who can assist them. This may or may not mean they have special functional requirements for the resources they want to access.

A

typical set of user needs and preferences shwing the

default and the user's individual choices.

A

typical set of user needs and preferences shwing the

default and the user's individual choices.

By rendering the user's needs and preferences profile as a resource, problems associated with the politically unpopular activity of labeling people by disabilities can be avoided. The technical problem that a single person will be associated with a number of AccessForAll profiles is also avoided as they can point at different times to any of a range of profiles. In addition, where there is a need for many users to share a profile, as with students in a lecture theatre, this is easily achieved. This approach was difficult to work within the DC rules for profiles but on a day ion 2007 when it became very important to solve the problem, a W3C Working Group considering a similar problem, released their first version of the POWDER protocol. The POWDER protocol provides a way for exchanging metadata about a resource but it also defines a collection of metadata as a resource, in that case establishing the useful term 'description resource'. This seems very appropriate.

A system working on the match, to ensure accessibility, will read the AccessForAll profile selected by the user (or user group) and use that information to test the metadata of potential components for the resource or service to be delivered. In the absence of an AccessForAll profile, systems will have to assume that a user has no special needs to constrain their relationship with resources and services at that time.

When a system is to be used simultaneously by two users who point to different profiles, it may depend on the circumstances how this is to be handled. If they are to share a screen, their needs will have to be harmonized. If they are working on the same application but separately, as when two remote users share a chat session, their individual needs should be accommodated. When the two users are, for example, a corporate group for whom there is a corporate set of ‘needs and preferences' that conflict with the individual's essential needs and preferences, the latter should be matched in preference to the former.

A more complicated example occurs where, for whatever reason, there is a need for a visual relationship but the objects being viewed need to be larger than they might be when used on a stand-alone desktop computer. Such a case occurs frequently when resources are displayed on a large screen before a large audience. For this to be an accessible relationship, it does not need to be non-visual but there are some qualifications to be made to the visual qualities: the text and images need to be enlarged. Exactly how large the text should be will usually be best decided by the author in a situation where the details of the relationship are well-known, as for the large audience, but should always be available for customization where individuals may have special needs.

At this point it should be noted that while the user's PNP is described by a metadata record, it is itself metadata in another sense. The value of this is that it can be used in conjunction with resource metadata in the matching process for accessibility.

The vocabularies for the metadata to be associated with the resource or service and with the user's needs and preferences for accessibility have been carefully matched in the AccessForAll profiles. Other technical device information might also need to be conveyed to the resource server but it is expected to be covered by the work of the W3C Device Independence Working Group or others using CC/PP.

For all preferences, usage is required to determine if the user must or must not have it or if they merely have a preference for the setting. Flashing content, for example, can be dangerous for some users and content with nothing but graphics will be useless to a blind person unless they have a friend available to describe it to them.

As the vocabulary reaches its most detailed position, it is often possible to adopt existing standard vocabularies as has been done throughout the AccessForAll profiles. For example, the vocabulary for settings for dynamic Braille displays is established and AccessForAll has no reason to redefine it.