from La Trobe audit (Nevile, 2004)

Site Navigation

Contents of Thesis ack'ments - Introduction - Context - Accessibility - W3C/WAI - LitReview - Metadata - Accessibility Metadata - PNP - DRD - Matching - UI profiles - Interoperability - Framework - Implementation - Conclusion - References - Appendix 1 - Appendix 2 - Appendix 3 - Appendix 4 - Appendix 5 - Appendix 6 - Appendix 7

AccessForAll is a strategy for increasing accessibility by exploiting available technologies to match digital resources to users' individual accessibility needs and preferences. This is achieved just in time for the delivery of resources to users by working with descriptions of an individual user's accessibility needs and preferences and relating them to descriptions of resources' accessibility characteristics. This strategy supports cumulative and distributed authoring of accessible components for resources where these are missing, and the reconfiguration of resources with appropriate components for users.

Assembling Web resources in an integrated way for delivery to the user is defined as just-in-time accessibility and can increase the availability of accessible resources. Moreover, compared to resources that are accessible to every potential user, universally accessible resources, these resources are less expensive, easier to develop (in terms of skills required), and developed using more satisfactory practices for authors and publishers. In addition, the provision of accessible content can be improved so significantly by the use of specifications-compliant accessibility tools, adopted by moderately competent computer users with no accessibility training, that it is cheaper and more effective to rely on the technology than yet-to-be-developed high-levels of human expertise.

The new approach involves a shift of responsibility from individual authors to technology and a supporting community. The shift means increasing responsibility in the final provision of resources, and thus, of server software. The servers need to check the resources and possibly arrange for services to manipulate and reassemble them before delivering them. The accessible components need to be suitably described to enable their discovery. The components that constitute the final resources may be distributed. This means there is a need for metadata standards that promote interoperability. Finally, there is a need for descriptions not only of resources but also of user needs and preferences.

Accessibility is defined as the matching of delivery of information and services with users' individual needs and preferences in terms of intellectual and sensory engagement with resources containing that information or service, and their control of it. Accessibility is satisfied when there is a match regardless of culture, language or disabilities (Ford & Nevile, 2005). For individual users, matching their needs is of primary importance and in some cases critical to their ability to function. It should be noted, however, that this does not mean some users only want resources that are dull or boring but simply that resources should be adjusted and adapted to suit the stated needs of individual users at the time so everyone can have what will be best for them.

With respect to content, accessibility can be dependent upon a number of factors. A user needs to be able to use the range of sensory modalities upon which access to the content depends. Where a person at a particular time does not have the necessary sensory capability, alternative content in another modality may be required. In some cases, the modality of content can be altered and this is particularly true of text.

This chapter contains some content that was presented in France at the ASK-IT International Conference in 2006 and at the AusWeb 2005 Conference in Queensdland, Australia.

What is significant, beyond the usual benefits from working with metadata before the final delivery of the resource, is that metadata is not the resource; it is not necessarily created by the same author as the resource, and it can always be added to, authored by someone else. It can be created by the resource author and stored as part of it or with it or it can be created by a complete stranger to the resource author and stored elsewhere.

In a case where a student finds a resource they can use without vision, and that discovery may be of interest to others, for example blind people and those whose eyes are ‘busy’ when they need access to this information, the student can create some metadata to help those others find the resource. A student who wants a resource and realizes that there are captions available somewhere else that describe the images in the resource, can collect both the original resource and the captions and use them together. That student can later connect the resource and the captions by metadata, despite their being authored by different people in ignorance of each other, Someone who translates those captions into another language can add to the metadata about the resource (not necessarily storing the new metadata in the same file or place as the first lot of metadata), so that other students who have both a need for the captions and the alternative language will be able to find the resource components they need. In this way, metadata can achieve what the original author of the resource failed to do for whatever reason, and thus enrich the original resource in the process. The accessibility of the original resource is increased in two ways: first, the metadata can be used to discover it and check it for suitability and secondly, the addition of an alternative can make its intellectual content accessible in circumstances where it previously was not.

An example of the difference between the former approach of depending on the production of universally accessible resources and the shift to combine the use of metadata is well illustrated in Australian universities. As in many other countries, Australia has anti-discriminatory legislation that means any student at a university has the right to accessible versions of all the resources provided for students. A typical university will interpret this to mean that they must author all resources in universal accessible format (and typically will do this for only 3% of the resources) whereas a university using the AccessForAll approach could notify a student who has recorded their user requirements that a resource is not suitable for them and either re-author it or find a suitable alternative and link it to the original by metadata. It is true that a typical university can attempt to author an accessible version of the original resource but it is notoriously difficult to make an inaccessible resource accessible; finding alternative resources already in the chosen format is probably easier. Providing materials that are accessible within 24 hours of a request would be considered much better than having only 3% of the resources available; would probably make the resource suitable for that student while universally accessible does not always achieve this, and would add to the metadata of the original resource so that next time a student searches for it, there will be more options available. It is perhaps relevant to repeat here that, without metadata, a universally accessible resource probably will not be found by someone who needs it. The AccessForAll approach being advocated means a shift from just-in-case to just-in-time and, as in many other circumstances, the latter can be much more economical (and, in this case, achievable) (Nevile, 2006).

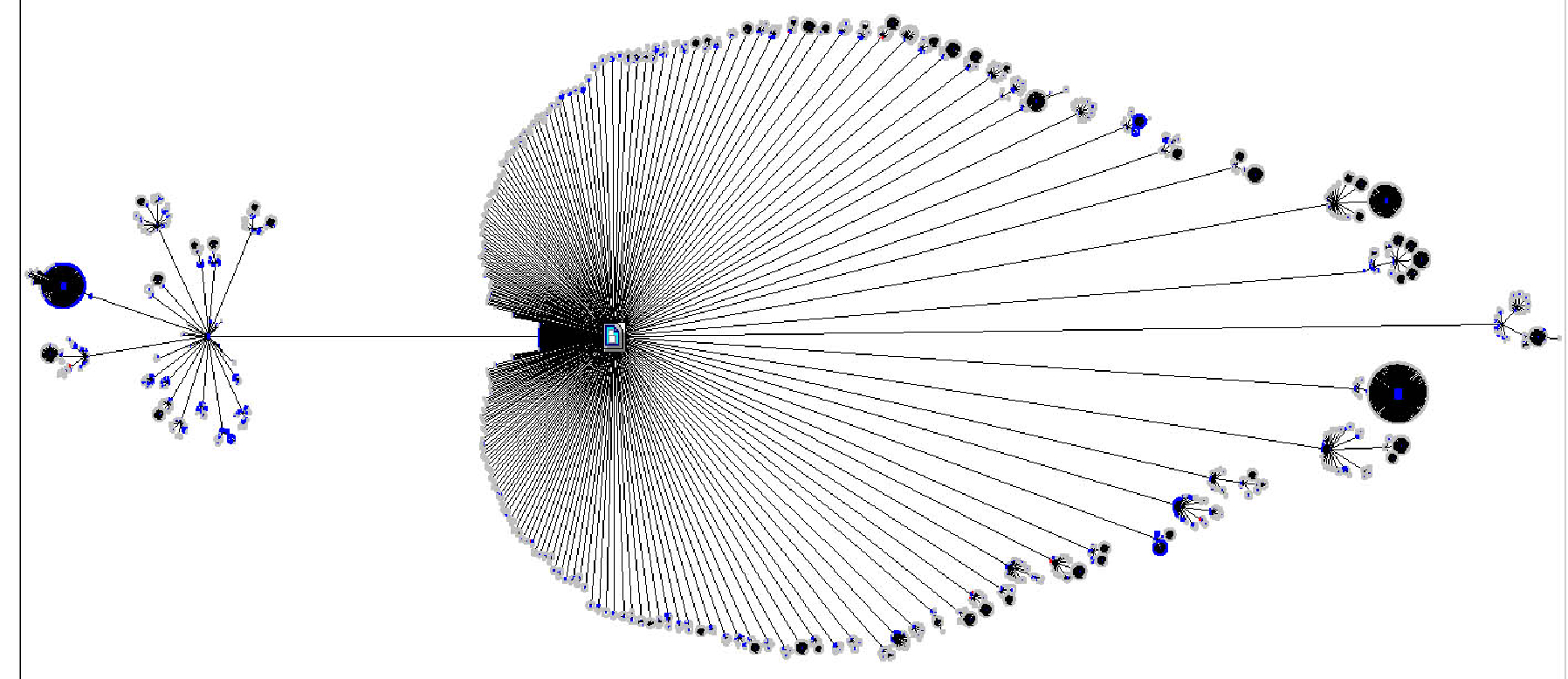

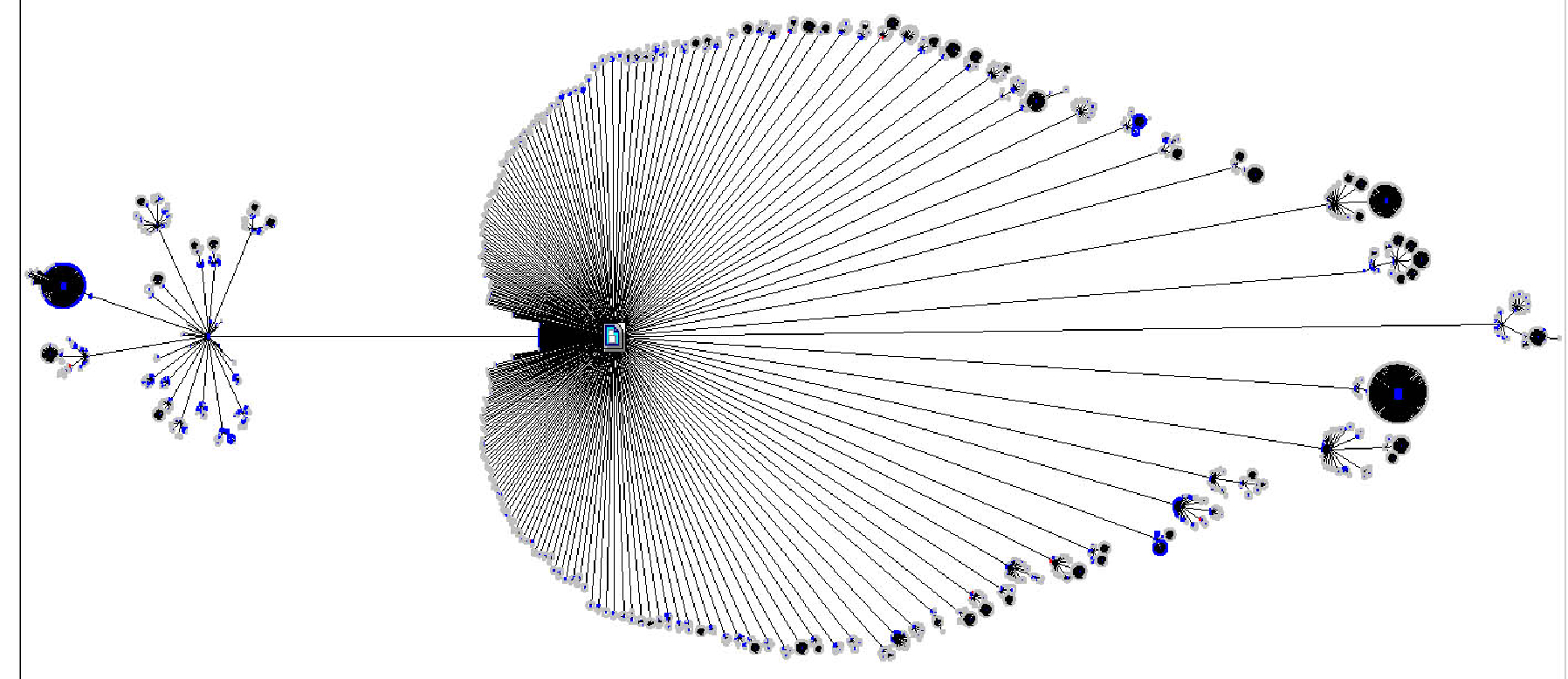

One of the reasons Web developers use metadata is because it allows them to dynamically compose Web pages. The audit of content at La Trobe university demonstrated this dramatically:

from

La Trobe audit (Nevile,

2004)

The TILE process provded both a proof of concept and a model for the matching of resources to people's needs and preferences.

A diagram displaying the behaviors for interoperability using ACCLIP and ACCMD in TILE. The diagram is a flow chart displaying the start and end states for systems analyzing a learner's ACCLIP against a primary resource's ACCMD (http://www.imsglobal.org/accessibility/)

The TILE model has the benefit that within the TILE system, all the necessary components are available. The resources are put together dynamically so it demonstrates the desired outcomes but it does not offer a model for situations where either metadata, or sought components, are elsewhere and not identified, where the resource is being made accessible to the user just-in-time.

Given that few resources are universally accessible, one can assume that most resources will need attention if they are to be rendered accessible for a particular user. As a strong motivation for accessibility often arises in a community of users rather than authors, it is not uncommon to find a third party creating an accessible component for an existing resource or part of a resource. Usually closed captions for films, for example, are produced by a party specializing in captions . So are the foreign language versions of the spoken sound tracks. ubAccess has a service that transforms content for people with dyslexia; a number of Braille translation services operate in different countries to cater for different Braille dialects, and online systems such as Babelfish help with translation services.

Creating the accessible alternative components and making them available for use is shared by accessible content authors and repositories. Once there is an alternative for a resource component, it is a pity if a new one has to be created just because the existing alternative cannot be found. This means, of course, that repositories of accessible content should be online and their collections available and discoverable (see below). In the case of education, there should be no barriers to the development of networks of distributed accessible components.

Just as user needs and preferences must be described in a common, machine-readable language, so must digital resource accessibility characteristics.

The difficulty with describing any resource is that it is almost always composed of a number of items and it may be only one or some of those individual items or objects that are inaccessible. This means that somehow the alternatives have to be organised in a logical fashion. They may, of course, also have to be organised and presented together, even where some of them are not co-located.

Most resource descriptions (DRDs) are done at resource level. Having a distributed model for resources where they are described at object level is an extra challenge. It seems sensible to identify the original objects, and to classify those that are needed in special circumstances (to be substituted for them, or to augment them) as alternative resources.

Following the description requirements for the PNP makes sense but it may mean having many descriptions for many items. In order to manage this, automating at least part of the process and storing the results is necessary. Determining all the characteristics of a resource or object that will be needed is a mixed activity with some being determinable automatically, such as the format of the digital file, and some being subject to human judgement, such as whether a text description of an image is really equivalent to the image or not.

As there are legal requirements that relate to the accessibility of content objects, it is not always possible to be sure that the descriptions available are reliable. For this reason, a notion of trustworthy descriptions is important. Similarly, it is important to know when the resource or object was evaluated, as it may change over time. As the content may be distributed, so may the descriptions of it, and so they should all be in a standard form and interoperable.

Alternative content components are often produced by specialist businesses such as caption centres. These components may already be profiled according to local specifications. If they have no profile records (metadata) or have them in a local form, these can be created, or otherwise they can be harvested and transformed into the common format. They can then be included in the discovery hub for distribution via a Web service.

The AccessForAll specifications produced by the IMS-led collaboration provide a suitable taxonomy and specifications for digital resources.

When every effort has been made to make a resource technically accessible, it can still fail to be useful to a user for non-technical reasons. A user who is dyslexic or a blind may find that resources that are very good for their colleagues are not at all appropriate for them. In such cases, what are called ‘equivalent alternative resources' should be provided. Such resources serve the same purpose, but achieve the goals in a different way. Their description is, therefore, not the same as that of the original resource, even though the purpose might be.

Identifying alternative resources with a similar purpose normally requires human judgement. There is already a suitable common language for learning resource descriptions in the IMS Global Learning Consortium's Learning Design specifications http://www.imsglobal.org/learningdesign/.

Services for automatically generating alternative content are being developed using Semantic Web technologies. Already some components can be retrieved from existing services such as the Smart Web Accessibility Platform [SWAP] and AnnoSource, a La Trobe student project for a service that helps with rendering inaccessible content accessible (Kateli,2007).

Finally, there is a need for a service that provides the right combination of content and services for the user, where and when they need it. This means there needs to be a way of bringing together all the pieces, including the user and resource profiles, the context information, and the pieces that are to be assembled for delivery to the user as the resource they require.

For a user, or an assistant working with them, it must be possible to create the necessary profiles and to change them for the immediate circumstances. In addition, it must be possible to make formal descriptions of the resources and link all of these together for the matching process. There are several layers of discovery involved. There is more than just discovery information needed, however, and therefore a need for systems that facilitate the making of such descriptions.

The Inclusive Learning Exchange (TILE) is an example of a learning management system that works by checking the user's profile and then finding objects from which to compose a resource that suits their needs. As TILE includes a tool for creating and editing the user's profile, this can be done while the user is using the service. TILE uses the AccessForAll metadata profiles to match resources to user's needs, with the capability to provide captions, transcripts, signage, different formats and more to suit users' needs.

Fairfax, in Australia, has offered a striking economic reason for being concerned about accessibility. In 2003-4, they redeveloped their website with accessibility in mind and the result is a saving of an estimated $AUD1,000,000 per year in transmission costs. A bigger publisher would save even more. http://webstandardsgroup.org/resources/documents/doc_317_brettjacksontransitiontoxhtmlcss.doc

Flexible assembly satisfies the requirements for the users, allows for more participation in the content production process and has the benefit that it limits the production and transfer of content that will not be of use to the recipient.

Descriptions of the accessibility of content of large collections can be done with tools designed for that purpose. Publishers can identify potential problems and gaps in their resource collections in advance.

The strategy proposed, using technology to augment, supplement and in some cases replace author expertise, is most likely to be achieved by a combination of tools than the adoption of any particular tool. Many of these are not yet available as Web services but are already available as system components. The big changes will be possible when they are made into services as this will increase the network capabilities of the systems, and thus the quantity of sharing that will be possible. The possibilities will only be realised if there is commitment to them. This is not so difficult to imagine: the achievements of normal people using word processors, electronic spreadsheets and presentation tools today are similar to what can be expected for accessibility in the future with the tools and practices proposed.

The work behind the user and resource profiles that allow for matching of resources to users' needs and preferences, was predicated upon the notion that digital resources are easily manipulated by computer applications. http://dublincore.org/groups/access/

In times of increasing complexity and reliance on technology, it is important to ensure that what is being gained is increased quality of life. Currently huge demands are made on all as a result of the move towards a more technology-dependent world, and opportunities lost by early introduction of new technologies are being repaired by careful development of newer technologies, but it is important to balance cost-effectiveness with outcomes. If we choose to support everyone in terms of greater adaptability to personal needs and preferences, and can do so by placing greater reliance on collaboratively developed technologies, we should find it easier to manage the financial and equitable burdens placed upon us.

For accessibility reasons, it is essential that the user's profile always overrides all other profiles, as is the case with cascading style sheets.

from "Using Metadata to Adapt Ubiquitous Web 2.0 Resources to Individual Users’ Accessibility Needs" submitted to DC 2006.

The question being considered in this paper is what is necessary for an accessibility service to find a suitable resource or component in a distributed environment. The availability of Web services such as language translation can be a factor but is considered out of scope at this stage.

In the usual discovery process, users define the topic of interest and one or more other properties. In the case of an AccessForAll search, the user's PNP imposes additional constraints on the results of the search. Previously, it has been assumed that the additional constraints could be part of the search parameters. In that case, the diagram taken from an earlier paper (9) and shown below would explain the process. In fact, we find that this would leave us without what we might need to generate more metadata in the hope of doing a second, successful search. A potential source for this additional metadata will probably be resources with the sought-after intellectual content that are rejected because they are not accessible.

This means that more than the suitable resources should be identified and then these should be filtered according to a user's PNP, so that there are resources available from which to generate more metadata.

For this reason we have decided to modify the process, and the original diagram (Fig 1) as shown in the second diagram (Fig 2).

The reason for the change is that if the search is a combination of the PNP (user's constraints) and the usual discovery metadata, there will be nothing to work with if the search fails. This new way means objects with the relevant content will be found, and from them, hopefully, metadata can be obtained or generated to help in the discovery of suitable alternatives.

Fig 1: a process diagram from 2005 (9)

Fig 2: the modified section of the original diagram with a separate filtering process shown highlighted.

There are a number of possibilities. Let us assume somewhere a suitable result exists. (In case there isn't one, we will have to specify a fail condition.) So let us imagine we are seeking an alternative for an image that is usually inserted into a resource. Let that resource be a map, so we are looking for either a textual version of the content of the map or a recorded verbal description of it, and for our current purposes, we assume at least one such target resource exists. In other words, the problem is not to find a suitable resource so much as to find a resource with the same intellectual content as the map we already had.in a situation where we did not find that alternative in the first search. This is not a new problem. We are, then, dealing with a classic problem of how to find resources like a given one that are not described in a way that has already found them. Many search engines offer a facility to ‘find similar'.

There are a number of potentially useful processes for doing this. For example,

- Jeon et al have proposed a method for finding similar questions by reference to the answers to those questions (Jeon J, et al “Finding Semantically Similar Questions Based on Their Answers” in Proceedings of the 28th International ACM SIGIR Conference, pp. 617-618, 2005, online at <http://ciir.cs.umass.edu/~jeon/papers/p061-jeon.pdf>).

- Another approach is to find similar words to those used for the original search and then use the new set of words to search for more resources (See the work of Denis S. Otkidach and others on the Python list, esp. at <http://mail.python.org/pipermail/python-list/2004-November/251224.html>).

- Google offers some simple approaches: press the ‘Similar Pages' button, use the Page-Specific Search selector on the Advanced Search page, or use the related search operator. They even offer a browser button for those who are doing this frequently (Google online at <http://www.Google.com>). Google provides a detailed explanation of how they find similar resources (Google Similar Pages online at <http://www.googleguide.com/similar_pages.html>).

We are convinced that it is not fanciful to propose that resources can be found, using algorithms to form new queries, especially when some resources are available from which to generate new queries.

We explain this by reference to the FRBR model that shows how resources can be related through their original work or expression. Not every resource is related in the same way, simply because independently, more than one person in the world may chose to produce a resource that is similarly related to a particular topic.

The aim of the [FRBR] study was to produce a framework that would provide a clear, precisely stated, and commonly shared understanding of what it is that the bibliographic record aims to provide information about, and what it is that we expect the record to achieve in terms of answering user needs. (IFLA, “Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records Final Report” 1998, online at <http://www.ifla.org/VII/s13/frbr/frbr.pdf>) (p. 2)

The Functional Requirements of Bibliographic Records (FRBR) study did not focus on the content or structure of bibliographic records but rather the entities of interest to users of bibliographic records, the attributes of each entity, and the types of relationships that operate between entities.

The study used an entity analysis technique, isolating key entities of interest to users of bibliographic records, then identifying the characteristics or attributes associated with those entities and the relationships between entities that are most important to users.

Significantly, the report states:

The model developed in the study is comprehensive in scope but not exhaustive in terms of the entities, attributes and relationships that it defines. The model operates at the conceptual level; it does not carry the analysis to the level that would be required for a fully developed data model.

In this paper, we accept the invitation from the reporting committee to view the FRBR model as a starting point for further work. This is not to suggest that the FRBR study did not achieve its goals. There have been great changes in the world of resources since it was produced and we think it is time to investigate whether the model covers the situations of interest to us. We are aware of the vast range of circum-stances that were considered in the development of the FRBR model, and that it did not attempt to specify in detail for each possibility, but ask whether it was concerned at all with what is now a major development in the provision of accessible resources, namely, the capacity of computers to match or tailor resources to suit individual user's needs and preferences at the time of delivery.

We investigate this issue with respect to the FRBR model not only because that is such a useful model but also because it is an abstract model against which many metadata models can be evaluated for coverage of user requirements. Although the FRBR model is said to relate to bibliographic records, and was focused on them in the beginning, it has been interpreted for use in the digital information world (Joint Steering Committee for Revision of AACR RDA, “RDA: Resource Description and Access”, 2005 online at <http://www.collectionscanada.ca/jsc/rda.html>).

Previously, Morozumi (Morozumi, A, (in Japanese) “A Metadata Schema Model for Resource Selection based on User's Characteristic and Its Use-Environments”, 2005, Digital Libraries, No.29. University of Tsukuba.) has done extensive mapping of metadata schemas to the FRBR model to investigate the use of the FRBR model to match the intellectual content needs and preferences of users, and how resources with the same or similar intellectual content but presented in different forms, can be understood. This paper builds on that earlier work and other work to do with AccessForAll accessibility by Nevile (Nevile, L, “Anonymous Dublin Core Profiles for Accessible User Relationships with Resources and Services“, 2005, online at <http://purl.oclc.org/dcpapers/2005/paper09>).

In some cases, metadata models have specific and narrow requirements they aim to address. In our case, we work with the Dublin Core Metadata Terms (<http://dublincore.org/documents/dcmi-terms/>) that are designed to be a minimal interoperable core set; the Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS) (The Library of Congress, ”Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS)”, 2006, online at <http://www.loc.gov/standards/mods/>) which is designed to bring descriptions from MARC catalogue records into use as XML metadata, and ISO JTC1 AccessForAll metadata (<http://jtc1sc36.org/>) for adapt-ability for accessibility purposes.

We note that most countries have legislation requiring the provision of accessible resources; that adaptability is essential to this, and thus the significance of essential metadata relating to the adaptability of resources.

We adopt the definition of the user requirements of an inclusive environ-ment (Coombs, N & Treviranus, J “Bridging the Digital Divide in Higher Education”, 2000, online at <http://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/EDU0028.pdf>) from the ISO JTC1 standard for Personal Needs and Preferences (PNP) (FCD 24751-2, “Individualized Adaptability and Accessibility in E-learning, Education and Training Part 2: Access For All Personal Needs and Preferences Statement” online at <http://jtc1sc36.org/doc/36N1140.pdf>). We compare them with those on which FRBR was based to determine to what extent they were included explicitly or implicitly. These two standards provide a stable set of AccessForAll requirements and attributes/relationships that are intended to be used with many metadata sets that focus on the other aspects of resources. We then consider the FRBR model to see if it indeed provides for these requirements by considering the relationship between the FRBR attributes and relationships and those of metadata that is required for adaptability, basing our definition of these on the ISO standard for Digital Resource Description (DRD) (FCD 24751-3, Individualized Adaptability and Accessibility in E-learning, Education and Training Part 3: Access For All Digital Resource Description online at <http://jtc1sc36.org/doc/36N1141.pdf>).

Finally, we map DC and MODS elements to the FRBR model to determine to what extent the DC and MODS sets provide for adaptability in the way necessary to support accessibility of resources.

In an inclusive environment, it is not sufficient to deliver an item with the required intellectual content. It must also satisfy the user's accessibility needs and preferences. This places greater emphasis on various characteristics of the item than has previously been necessary.

A poem engraved on a tombstone, shown in a photo of the tombstone, is not accessible to a blind person: although the genre of ‘poem' is text, the resource is an image so the user interaction is based on vision. A blind user will need a tactile or auditory version of the intellectual content, both of which can be delivered from a range of manifestations other than an image, including textual and Braille versions and an audio recording.

There are many situations in which users have constraints for their use of resources that go beyond the limitations of their devices and that are not necessarily associated with any disabilities. Being near a noisy construction site may limit the use of a given resource (the user may need an alternative to an auditory resource). A user with limited vision may need resources without images. Whether such needs arise because the person is blind or because they are driving a car; their functional requirements are the same.

An automated accessibility service will determine the suitability of a resource and, if necessary, replace or augment it with an appropriate one. This process of matching is based on the AccessForAll accessibility approach already being implemented in educational systems (e.g. The Inclusive Learning Exchange online at <http://www.barrierfree.ca/tile/>).

Many people assume that if a user has special requirements, such as large yellow text on a deep blue background, that they would state this as a require-ment and the accessibility service would match resources to this requirement. Although it is possible to find a single resource with such characteristics, in a world where digital resources are rendered on demand for users, this does not always work. A book, on the other hand, either has large text or it doesn't, or has black on white text or some other combination. Web resources, such as Web pages, do not necessarily have a fixed form.

Some files (e.g. PDFs) transmitted via the Web may have a fixed form; many Web pages do because they are constructed that way. Users' needs and preferences should be described in a generalized way so they can be used across all types of resources, static (as a book or badly constructed Web page), or dynamical, as in most cases,

Users sometimes specify their needs in style sheets and simply direct their Web browsers to use their personal style sheet in preference to that of the content provider. In such a case, the user needs a resource that has its presentation separated from the content so that their style sheet will work. In other cases, the user will have to specify their needs in detail in a machine-readable profile that can be applied by an accessibility service.

The personal needs and preferences of a user, including an agent, can be described using the ISO AccessForAll standard. This Personal Needs and Preferences profile is known as the PNP. Once a resource is found, and identified, it is selected for a user (FRBR terms). According to the AccessForAll approach, resources should be filtered by the user's PNP (Morozumi et al, 2006, “Using Metadata to Adapt Ubiquitous Web 2.0 Resources to Individual Users' Needs“ submitted to DC 2006.).

A PNP is a record of user needs and preferences, including both because for some people a need is crucial, and if not satisfied the resource will not be useful at all, while for others the stated need is a preference, and if not satisfied, may make for difficulties that will be acceptable to that user.

The PNP was developed by a commun-ity that is very, possibly too, familiar with the W3C universal design approach to accessibility. The PNP assumes, according to that approach, that a user with special presentation needs such as particular font sizes will be satisfied if the resource is access-ibility compliant according to the relevant criteria, as detailed in the W3C WCAG (<http://www.w3.org/TR/WAI-WEBCONTENT/>) and considered to be part of the conformant use of markup languages such as XHTML (<http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/>). The PNP is structured so that at one level, display transformability is required, and then, at a lower lever, the details of the transformation are recorded. (This structured approach is consistent with the DCMT ideas of generalization contained in what was once known as the ‘dumb-down rule'.) A user who needs a font size of xx, needs a resource that fits their specifications exactly or one with a transformable display.

There are three categories of user accessibility adaptation requirements: control, display (or presentation), and content.

Control issues include limits on the user interface, such as a current inability to use a mouse.

Display or preference issues include such things as particular font sizes or colors, screen reading of text, or layout of a tactile presentation as Braille, etc.

Often the most important requirement is the mode of interaction with the content. This can be set by the PNP as any combination of visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory and textual. Although ‘textual' is different in kind from the others, it is a form that, if properly constructed, can be transformed automatically into auditory, adapted visual (such as large font), or tactile Braille (in most cases). There are other characteristics included such as avoiding a hazard that occurs with flashing objects that can cause some people to have seizures, and the need for inclusion in the resource of support tools, such as a dictionary.

In terms of content needs, personal preferences might be such as that text should be of a certain reading level, in a particular language, etc. (Note that even some of these characteristics are now becoming transformable given the range of services emerging on the Web.)

FRBR users are not just end-users of resources:

the users of bibliographic records are seen to encompass a broad spectrum, including not only library clients and staff, but also publishers, distributors, retailers, and the providers and users of information services outside traditional library settings.

The study also takes into account the wide range of applications in which bibliographic records are used: in the context of purchasing or acquisitions, cataloguing, in-ventory management, circulation and interlibrary loan, and pre-servation, as well as for reference and information retrieval. (p. 4)

FRBR references:

the importance to users of aspects of both content and form of the materials described in biblio-graphic records. (p. 4)

FRBR attends to users' interests in the range of formats and genre in which intellectual content is available. Thus, if a resource can be found that satisfies the requirements in the user's PNP, it may be said that FRBR includes these requirements.

In our interpretation, however, this does not include the adaptability of a given resource. We make this assumption because there is no reference to digital as opposed to physical resources, nor to adaptation of them and, as a study, FRBR predated the adoption of technology that supports the adaptation processes.

The technology now being used in this context includes computer mark-up and other languages that support adapt-ability of resources, such as Cascading Style Sheets (<http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-CSS2/>), Scalable Vector Graphics (<http://www.w3.org/TR/SVG/>), eXtensible Markup Lan-guage (<http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-xml/>) and, in particular, the W3C guidelines for using these technologies to promote accessibility.

While a resource might have the specific characteristics initially required by the user, the failure to satisfy adaptability requirements means that the user cannot change the resource if their requirements change as they interact with it. This is considered an essential characteristic of accessible resources, and so, even if the resource is initially accessible to the user, unless it is transformable (and similarly control flexible), it will not be considered suitable by an AccessForAll accessibility service. This concept may be considered a failing of the AccessForAll principles but it is also the principle behind the W3C specifications, showing it is considered important by those who work in the field. It is a noted problem, however, and implementers should be advised to ensure that a resource is not missed because of it.

In the FRBR study, the bibliographic records were stated to:

cover the full range of physical media described in bibliographic records (paper, film, magnetic tape, optical storage media, etc.); they cover all formats (books, sheets, discs, cassettes, cartridges, etc.); and they reflect all modes of recording information. (p. 7)

It seems a reasonable assumption, even given these comments, that the records are for the physical objects that are produced, even by digital means, but not that they are for digital resources for use in an electronic environment in which they could be transformed or adapted on-the-fly, as required by the AccessForAll model.

In the description of the entity known as item in the FRBR model, the thing that is finally delivered to the content user, the physical form of the object, or set of objects, is emphasized. (p. 23)

The study takes into account the wide variety of applications, both within and outside a library setting, in which the data in bibliographic records are used: collections development, acquisit-ions, cataloguing, the production of finding aids and bibliographies, inventory management, preser-vation, circulation, interlibrary loan, reference, and information retrieval. (p. 8)

Although there is no mention of any-thing like the adaptation of resources in this list, it is possible (but unlikely) there was an awareness of the problem expressed in the details of record use:

to determine the physical require-ments for use of an item as they relate either to the abilities of the user or to special requirements for playback equipment, computing capabilities, etc. (p. 8)

In the end, the FRBR model assumes four user tasks: find, identify, select and obtain.

We conclude that the FRBR user requirements did not include those contained in the PNP.

The FRBR model is based on entities considered to be of interest to users for the tasks identified by the FRBR study. The work on these entities makes it clear how resources, as delivered (or obtained), may be closely related to each other through the association of abstract entities.

In this paper, we are concerned mostly with the processes of selection and adaptation of resources, and so characteristics of the manifestation and item, according to the FRBR entities model. The FRBR study claims that:

Defining item as an entity

enables us to separately identify individual copies of

a mani-festation, and to describe those characteristics

that are unique to that particular copy and that pertain

to transactions such as circulation, etc. involving that

copy.

Defining the entity called item also enables us to draw relationships

between individual copies of manifestations. (p. 23)

As an example, we consider Shakespeare writing the play Othello and its translation into Japanese. Both endeavors are considered to be significant intellectual exercises leading to concrete output. FRBR abstracts two entities, work and expression, from the concrete manifestation of the plays that are reproduced as items.

Figure

1: Diagram showing 4 FRBR entities associated with two

resources and their possible relationships.

Figure

1: Diagram showing 4 FRBR entities associated with two

resources and their possible relationships.

The relationships of interest in the FRBR model, that help both distinguish and show similarities between entities, include such as based on, translated from, and they include relationships between entities as well as across entities, i.e. between an expression and its manifestation as well as between two manifestations. In particular, the relationships between entities based on their subject, is of interest to us. These include such as: adaptation, trans-formation, complement, supplement, etc. Where such relationships are recorded in the metadata, they can be of special value in the adaptation situation.

It should be noted, however, that the FRBR entity relationships can transcend an individual entity to one that is related by other relationships, that is, it may not be between two entities such as two manifestations, but rather through some abstract entities such as the expressions or works from which the concrete entities are derived. While this is a limitation in as much as a core metadata system such as the DCMT will not be suitable for recording this information, it is very useful to know of its existence.

In our case, it is the individual items that will need to match the user's accessibility requirements and so the adaptability of the manifestation that is of interest. We assume that whenever a resource is adapted, the intellectual content is maintained while the access to that content is adapted. This is true even when alternative content is required because the original content cannot be transformed or controlled. This means that the work and expression attributes of an alternative resource may vary as well.

We considered the attributes of works and expressions that are relevant to the accessibility adaptations and find that the only one is form.

With respect to a work, the form is the class of work or what might be called the genre, while the form of an expression is “the means by which the work is realized (e.g., through alpha-numeric notation, musical notation, spoken word, musical sound, carto-graphic image, photographic image, sculpture, dance, mime, etc.).” (p. 36)

FRBR's form is thus quite closely related to the access mode that is of importance in the accessibility context. A work that is realized in dance form will need to be presented to an eyes-busy user as an audible description, and so manifested as textual (FRBR's alpha-numeric notation) for automated reading, or auditory (FRBR's spoken word).

It is at the stage of realization (or instantiation) of the various forms of expressions into manifestations, that the potential for adaptability for access-ibility is enabled.

So we closely examine the attributes of manifestations and items.

Although the FRBR model includes an ‘access mode' attribute for manifest-ations, it does so with a very different meaning from the AccessForAll work. The only attributes of manifestations that may impact on resource access-ibility adaptation are:

· ‘file characteristics (electronic resource)' which are defined to relate to “characteristics that have a bearing on how the file can be processed” including things such as the encoding schemes and languages. (p. 48)

We note again that these attributes may be used to determine if a resource with fixed characteristics matches a user's needs while those needs are stable, but it would not help when the user's needs change.

We look next at the attributes of interest with respect to an item in the FRBR model.

While we are told that “The attributes defined for the purposes of this study do not include those associated with transactions of an ephemeral nature such as the circulation or processing of an item” (p. 49), we note that such processing is not of the type envisaged for adaptation of resources. We found no attributes of the entity class of items that relate to the adaptability of resources to satisfy varying personal accessibility needs and preferences of users. This does not surprise us because we have already identified the other entities (manifestation, expression and work), to be the relevant entities.

There are still more entities dealt with in the FRBR model, of which one is person, but that entity is not in any way relevant to our problems. It is used to describe the attributes of a person and the AccessForAll assiduously avoids any suggestion that accessibility is based on the attributes of a person.

We therefore conclude that the FRBR model does not, implicitly or explicitly, cater adequately for the adaptability needs and preferences of users.

FRBR is not a metadata schema and is not intended to be one. It is not implemented as metadata anywhere. It is a model for use by those who are working on metadata for user requirements. It was based on some well-established principles for metadata (at that time called bibliographic records), and usually applied to physical objects. It follows the traditions associated with bibliographic records but, nevertheless, FRBR provides an excellent base for the mapping and thus comparison of the many metadata systems now available.

We considered the relationship between the FRBR relationships and attributes of entities and Dublin Core Metadata Terms (DCMT), the MODS terms, and the ISO JTC1 Digital Resource Description (DRD) terms.

We found that DCMT (properties) describe what FRBR calls attributes of entities with the exception of the relation element. dc:relation is useful for describing relationships that can be of interest in the adaptability context, as demonstrated in the emerging DC Application Profile for AccessForAll adaptability (<http://dublincore.org/accessibilitywiki/>). The relationship bet-ween the attributes of dc:format and dc:type would be of interest but this depends on implementations, and is not in the metadata per se. dc:description and dc:audience may also be useful, depending on their use.

With MODS, we found a similar situation. Mostly MODS describes attributes, in the FRBR sense, but it does have a property relatedItem that could be useful in the adaptability context.

We found very little in common between the elements of the DRD and the FRBR model, which did not surprise us for the reasons already given above. Also, the DRD was designed to complement existing metadata schemas, not to duplicate them.

These results led to our observation that the DCMT and MODS terms are limited in respect of accessibility adaptability in the same way as is the FRBR model.

It is asserted then, that as the DRD represents the information as metadata that is required in the description of a resource to indicate its adaptability for accessibility, neither the FRBR model, nor examples of metadata such as the DCMT and MODS that are closely related to it, provide the metadata necessary for accessibility adaptability.

As described above (Section 4), form is the only attribute of FRBR works and expressions that relates to adaptation. On the other hand, there are attributes of manifestations that relate to character-istics of a resource that may need to be adapted, such as capture mode, typeface and type size. Fortunately, these are attributes of the resource that may happen to be suitable as they are for the user so that a resource as identified for delivery may satisfy the exact require-ments of the immediate user. In one sense, that is all we are concerned with. Unfortunately, though, while they are identified and described in their existing state, there are no attributes indicating if they are adaptable.

What this means in the FRBR context is that while it may be possible to determine if a particular resource suits a user by reference to that user's PNP, it is not easy to tell from FRBR type descriptions of resources if they will be adaptable as those requirements change.

Today, resources are so different from those originally considered by FRBR that one might hesitate to try to include them in the FRBR model. It is a question for further consideration then, whether the FRBR model should be extended to include attributes that describe the adaptability or just those that describe the current state of the resource, or not at all.

We believe the first choice is compelling in a world where adapt-ability is constantly being practiced as people change devices, locations, goals and tasks and almost all the devices used include some intelligence and adaptability capabilities.

While the majority of attributes of works and expressions are descriptive of the intellectual content of the resource, those of the manifestation are generally more relevant to the presentation of that content or interaction with it. This suggests we can focus on the attributes of manifestations when developing the requirements for resource selection for adaptation to individual user needs.

The dynamic nature of manifestations and items enables the AccessForAll adaptability approach, in accordance with the needs and preferences of users. As these are specified in the DRD, that standard would provide a good starting point for consideration of extensions to the FRBR model.

In this paper, we reported on a close examination of the requirements of users as defined for the FRBR study in 1998. We showed that the requirements at that time, and as used in the FRBR work, did not include those that are now considered necessary for an inclusive information system. We based our definition of user requirements on a new ISO standard and the information needed for those users on a matching ISO standard for the description of resources. We found no evidence that the FRBR model would provide such information. We found that none of the DRD metadata terms were included in the FRBR model. We mapped the DCMT and MODS metadata terms to the FRBR model and found that those metadata schemas had similar short comings.

We conclude there should be an extension to the FRBR model that provides for a more inclusive inform-ation environment for users We consider that this would bring the FRBR model more closely in line with what is happening in general with the Web, and its evolution towards what has been called Web 2.0. We hope that such an extension would also result in more attention in metadata systems on the information needed for accessibility.