the simple AccessForAll model.

Site Navigation

Contents of Thesis ack'ments - Preamble - Introduction -Accessibility - W3C/WAI - LitReview - Metadata - Accessibility Metadata - PNP - DRD - Matching - UI profiles - Interoperability - Framework - Implementation - Conclusion - References - Appendix 1 - Appendix 2 - Appendix 3 - Appendix 4 - Appendix 5 - Appendix 6 - Appendix 7

This dissertation develops a framework for what is called 'AccessForAll' accessibility. It responds to the need (established in the early chapters of the thesis) for a framework to explain and justify a new approach to accessibility. AfA enables content providers to create and offer more resources that can be adapted to individual needs and preferences to minimise the mismatch between people who especially, but not exclusively, have special needs due to disabilities, and resources published within what is described as the Web, the World Wide web of digitally connected resources. The context, history, stakeholders and other relevant factors have been explained elsewhere (The Preamble).

The aim of accessibility work, so-called, is to help make the information era inclusive. The work reported in this dissertation started with a close examination and analysis of the current accessibility processes and tools and moved on to a new approach that would complement the earlier approaches and finally to develop a framework that would explain and accommodate many improvements in a constantly widening range of contexts. Co-editing of internation specifications and standards for accessibility metadata, known as AccessForAll (AfA) metadata, was undertaken simultaneously with the development of metadata recommendations for a Dublin Core Metadata Application Profile module. The work now suggests the need for a 'quality of practice' approach to the process of content and service production that will support incremental but continuous improvement in the accessibility of digital information and thus inclusion in the digital information era.

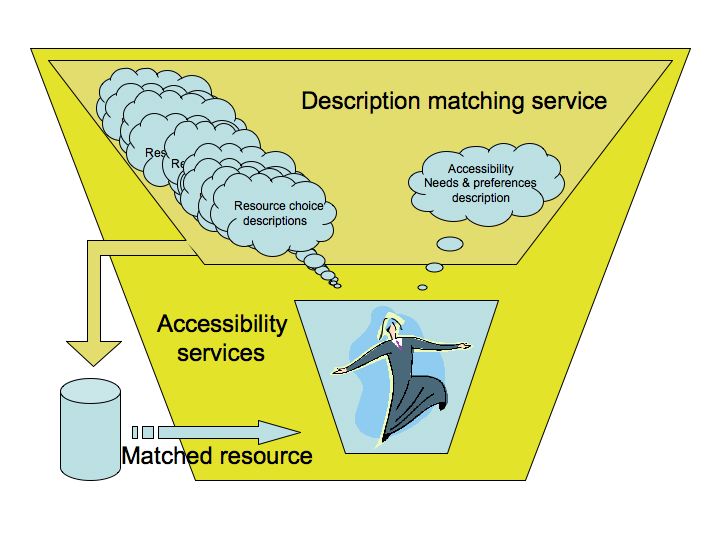

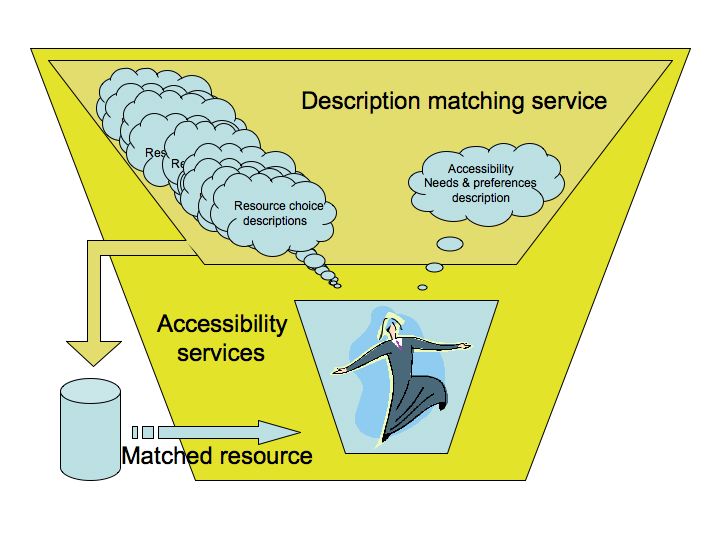

The framework to be developed is essentially the context for AccessForAll:

the

simple AccessForAll model.

By adding metadata to resources and resource components, new services are enabled that support just-in-time, as well as just-in-case, accessibility.

Nothing can prove that the Web will become more accessible but this dissertation shows that there are resources available that could be immediately transformed to take advantage of AfA metadata, to make the Web more accessible. AccessforAll is the development work of a team including the author, Jutta Treviranus, Madeleine Rothberg, Anastasia Cheetham, David Weinberg, Andy Heath, Martyn Cooper, and Hazel Kennedy, in particular. AfA includes new specifications for the classification of resources. Initially, these were for education only. They were further developed as an International Standards Organisation's multi-part education standard (N2008:24571). The continuing aim is to see their application broadening for resources across all domains, including being adopted by other standard bodies. The details of the specifications are not the focus of this dissertation which aims to show how and why and where these specifications can operate to achieve what results. The specifications themselves are publicly available elsewhere (ref).

This dissertation provides evidence that there is already metadata available that could be transformed to match the new standards, and that other suitable data could be generated automatically from existing data (see Ch 3?). Currently, such data is not available for use by those with accessibility needs, so individual users cannot discover in anticipation of the receipt of resources, if they will be able to access them. If the required descriptive data were available, individual users would be able to use it and thus the Web would be more accessible for individual users, as explained later.

The dissertation is a contribution of the author to the significant international AccessForAll effort.

A high proportion of potential users of the Web cannot make use of resources available on the Web for a variety of reasons. The resources discovered by a person using, for example, a Google search, may not be accessible to that person at that time even if they might be at other times. In many cases, there is another resource available somewhere that is equivalent in intellectual content. Such an alternative resource, often produced by an author other than the person who created the discovered resource, may be suitable for the user's particular needs. AccessForAll aims to make this possible.

The term accessibility is easily confused with access, a term commonly used to describe possession of facilities for connection to the Web or having the necessary legal rights to use resources. This kind of access is, of course, crucial to any user who is dependent on the Web. It is often dependent upon socio-economic factors, levels of education, regional and wider factors relating to communications availability and quality, or many of a number of similar factors. It also may be dependent upon such as intellectual property, state or private censorship, etc. AccessForAll is only concerned with users who, for whatever reason, cannot access Web resources, including services, when they are in possession of facilities that should be adequate; in other words, when they cannot access what they already have.

A significant problem for people with special needs, and their content providers, is that there are often intellectual property issues associated with the materials, especially when they are transformed for access by users. This is completely beyond the scope of this dissertation. It focuses on how such materials can be made discoverable and interoperable, seen as a precursor to any work that needs to take place to allow such interaction.

The dissertation refers to a detailed analysis of the standard approach to accessibility and the techniques employed to achieve it. This is contained in a set of practices and their explanation developed for use and used for some time as the basis for a university's accessibility strategy. (The work has not been maintained and so is not in continued use (Nevile1).) The dissertation is not about the techniques used to make digital information accessible to people with disabilities although unless there is information that is accessible to them, the metadata framework proposed cannot help. It is about how, when information is identified as of interest, a user with particular needs at the time and in the context in which they find themselves, can have the intellectual content of the resource that was originally discovered presented in a way that is matched to their needs and preferences. If necessary, this includes having components of the original intellectual content replaced or supplemented by the same information in other modes, or having it transformed, and it contributes the potential for this to be done, not the components themselves.

An interesting attribute of digital information is that people expect it to be available everywhere, and they expect to use all sorts of devices to access it. As they travel from one country to another, users expect to continue to gain the information in their language of choice, even though, for instance, it is about places where different languages are spoken. Sometimes users expect to get location-based, or location dependent, services and sometimes they want location independent services (see ch ?).

The context in which a user is operating is fundamental to the type and range of needs and preferences they will have. This dissertation embraces what is known as the Web 2.0. In this Web world, merely a progression from the original Web which was created by the technique of referenced resources and distributed publishing, users interact with resources and services that are made available by others, often with no knowledge of their source. Discussion of the new environment and the way it operates (see ch ...) is within scope as it provides the context for the work. It should be noted that the W3C work currently considers some Web content out of scope at this stage, in terms of some of their accessibility work (ref).

While it is clear that if a resource that contains some components that are inaccessible to a user will need to have those components transformed or replaced or supplemented for the user, it is outside the scope of this dissertation to deal with the problem of discovery of those components or the services that might be used for the transformation. The problem is considered not to be peculiar to accessibility so much as a problem related to modified on-going searching when resources that are discovered prove inadequate. This is being researched currently, especially at the University of Tsukuba, in Japan (Morozumi et al, 2006).

Out of scope also is any requirement to engage with the adoption of AfA by industry. The author is working with others, particularly collaborators at the Adaptive Technology Resource Center [ATRC] working with Industry Canada. They have vast experience in this matter and they are engaged in such work. Nevertheless, it is significant that there are implementations of AfA and these are discussed below (Ch ??).

The research questions for this dissertation are:

The main thesis is quite simple:

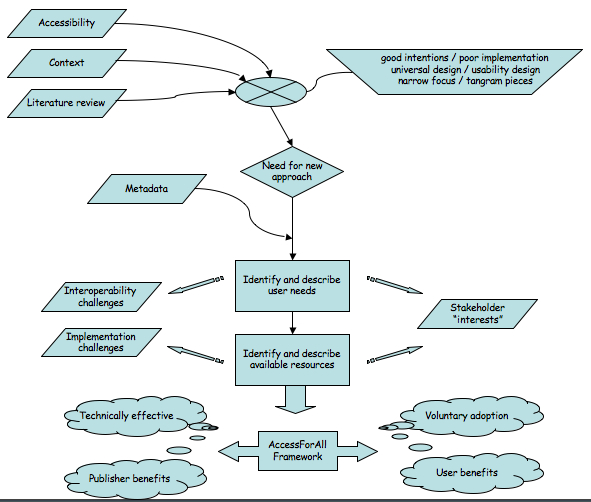

Considering the problems of accessibility, the context in which the problem occurs, and the available solutions, it has been necessary to define a more comprehensive framework in which the available parts can function, taking better advantage of the emerging technologies, without compromising either the interests of stakeholders or existing efforts, to achieve a better outcome for users and publishers.

Given an understanding of the field of accessibility, the context for it, and frustration with the lack of success and the results of recent research, it is evident that for all the good intentions, there has been poor implementation of accessibility techniques, that universal design is not a sufficient strategy even if it is applied, and that a narrow focus on specifications for Web content alone will not produce the desired results. This means there is a need for a new approach. By introducing metadata to describe user needs and preferences, it is possible to match them to resource characteristics, also described in metadata. By adding this possibility, without compromising interoperability of metadata or stakeholder interests, and by attracting implementation, individual access needs and preferences should be able to be satisfied. This approach is known as AccessForAll to distinguish it from earlier universal accessibility, universal design, universal usability and other approaches.

The research reported is not a traditional empirical study of an existing situation.

John Seely Brown (1998) differentiated between what he thought of as two main kinds of research, sustaining and pioneering. Sustaining research, he thought, is aimed at analysis and evaluation of existing conditions. The problem for researchers in fast-changing fields is that often, by the time sustaining research is reported, the circumstances have changed. As the original circumstances cannot be reproduced, the research results would need to be interpreted into a different context to be useful and in some fields, this cannot happen. In the case of pioneering research, the work is successfully implemented or, perhaps more often, forgotten. This is the sort of work that many technology researchers are engaged in: they follow what are traditional research practices to a point, but their work is evaluated differently and they need to engage with and accept different types of evaluation. We all know that the 'best' technology is not always the one that becomes the accepted technology. In the current technology environment, acceptance is crucial because it is the mass acceptance and use, what is often called 'the network effect', that makes the technology what it is. In the case of metadata, without mass acceptance there is usually nothing of particular value.

Pioneering research is what Seely Brown argued was the main output, and the valued output, from Xerox Parc in the 1980's. Staff at that institution developed some of the most significant ideas that have been incorporated into computers over the last 25 years. They were researchers but also inventors - people who had to know the needs, the problems, the context, et cetera and then invent something that might be useful. Their work has been tested not by an evaluation of their research methodologies, or how closely they followed the methodology they adopted, but rather by how useful and effective their work has become.

Within the field of pharmacology, research is combined with empirical research before the work is released onto the market or used with humans. In the case of developments of Web 2.0, a product or idea or standard's release is watched for adoption and it is only in hindsight that its 'effectiveness' is determined, and then by popularity. This is not always satisfactory. Experience has shown us that substantial reliance can be misplaced on technologies that do not solve the problem for which they were designed. It is essential that the intrinsic value of technologies is also accounted for. In the field of accessibility, extensive effort has focused on a single set of guidelines with what this dissertation argues are less than satisfactory results. It is important to evaluate AccessForAll accessibility to ensure this does not happen again.

Despite the interest in the idea of AccessForAll metadata, there is a substantial need for considerable research to create a suitable awareness of the context for the work and the value of the work. This means developing a strong understanding of the theoretical and practical issues related to accessibility, including practical considerations to do with professional development of resource developers and system developers, and the administrative processes and people that usually determine what these developers will be funded to do. It also involves the reading and writing of critical reviews of other work. In particular, while there is little doubt of the potential benefit to users with disabilities, it is not at all clear how to work with the prototyped AfA ideas to make them mainstream in the wider world, both in the world outside the educational domain and in the world of mixed metadata schemas.

Although metadata profiles have begun to appear, there is more work to be done in developing ways to enable distributed discovery of suitable accessible resource components for users and also to build the architecture that can take maximum advantage of the AfA approach. Both of these developments are outside the scope of this present work but they, too, are explained by, and therefore in some ways enabled by, the research reported.

Many use the expression 'research and development' to differentiate between them. Development work is often characterised as that without regard for the processes involved in achieving it. One is reminded of Mitchel Resnick's story of Alexandra whose project to build a marble-machine was rejected as not scientific until the process was carefully examined and she was ultimately awarded a first prize for the best science project (Resnick, 2006). In some fields, research is not just about writing a report, it is also about repeatedly designing, creating, testing, evaluating and reviewing something in an iterative process, often towards an unknown result but according to a set of goals. These are also important processes for development. Such processes benefit from rigorous scrutiny which can be attracted in a variety of ways, including by being undertaken in a context where there are strong stakeholders with highly motivated interests to protect. There is no getting away from the value of well-researched and documented research. This dissertation is just that.

In order to investigate how accessibility was working at a local and specific location, the author worked with several colleagues to audit the La Trobe University Web site. The results were submitted under a contract to the University and also in a session at the 2003 OZeWAI Conference. They were considered in a paper presented at the DC 2004 Conference (Nevile, 2004). The process was significantly eased by the combination of several available tools and produced metadata about all 48,084 pages reviewed. The tools could have been adapted to produce almost all of the metadata referred to below as AccessForAll metadata.

The Accessible Content Development Web site (Nevile1) was built in an effort to understand who might need to do what, how they might understand their roles, and what technical assistance they could receive. The aim was to provide a fast look-up site accessible by topic and focus, rather than the lengthy, integrated approaches required at the time by anyone using the W3C Web Content Accessibility Guidelines [WCAG]. Having been built, this site was given over to the La Trobe University who were supposed to maintain it. In the event, it was not maintained and it is now significantly outdated. The work involved extensive research including reviewing the literature and test ideas discovered from it, matched against the specifications from W3C and elsewhere, and experiments to design and create solutions.

For a major Braille project associated with the Accessible Content Development Web site, the first task was to understand the problems, then to see what partial solutions were available, and then to develop a prototype service to convert mathematics texts to Braille. In the last case, there was no need to survey anyone to determine the size of the problem or the satisfaction available from existing solutions - the picture was patently bleak for the few Braille users interested in mathematics and, in particular, the text was required by a Melbourne University student for his study program (ref). Ultimately, the research was grounded in computer science, where it is common to have a prototype as the outcome with an accompanying document that explains the theoretical aspects and implications of the prototype. In this case, the prototype work was undertaken by a student who was supervised by the author, who managed or personally did much of the other work in the project (Munro, 2007, etc???).

In "Design Experiments: Theoretical and Methodological Challenges in Creating Complex Interventions in Classroom Settings", Ann Brown (1992) describes the problem of undertaking research in a dynamic classroom. She was, at the time, already an accomplished experimental researcher, but argued that it was not possible or appropriate to undertake experimental research in a changing classroom. The problems referred to were related to the complexity of research closely associated with development in a dynamic context. In the case of AccessForAll, the context was not fixed and so did not afford research of the kind associated with numerical analysis but rather, called for clear documentation of the problems to be solved, the context, the possibilities and the implications of the proposed solution. This dissertation provides that documentation. Brown argued that the classroom circumstances necessitated the development of methodologies that would usefully analyse what was happening in the changing classrooms and provide useful information for others wishing to replicate the model and results in other classrooms. This dissertation aims to provide useful information for those wishing to use metadata to increase the accessibility of the Web.

Problem-solving and learning are similar activities. Educationalists aim to improve learning environments; accessibility specialists aim to improve accessibility problem-solving environments. They want better practices and better understanding and evaluation of those practices. In "Design-based research: An emerging paradigm for educational inquiry",

The authors argue that design-based research, which blends empirical educational research with the theory-driven design of learning environments, is an important methodology for understanding how, when, and why educational innovations work in practice. Design-based researchers’ innovations embody specific theoretical claims about teaching and learning, and help us understand the relationships among educational theory, designed artifact, and practice. Design is central in efforts to foster learning, create usable knowledge, and advance theories of learning and teaching in complex settings. Design-based research also may contribute to the growth of human capacity for subsequent educational reform (DBRC and D.-B. R. Collective, 2003).

The complexity of the accessibility work is not unlike that of education; everything is constantly changing, including the technology, the skills and practices of developers, the jurisdictional contexts in which accessibility is involved and the laws governing it within those contexts, and the political environment in which people are making decisions about how to implement, or otherwise, accessibility. There are also a number of players, all of whom have different agendas, priorities and constraints, despite their shared interest in increasing the accessibility of the Web for all.

The list of standards bodies and stakeholders (below), shows some of the major players and their interests in the work that was being undertaken. All of these stakeholders had to be won over as there is really no other way that technologies such as metadata schemas proliferate on the Web, and if they don't the technologies are not useful, as explained above. 'Winning over' bodies that use technologies often means providing a strong technical solution as well as compelling (in their eyes) reasons for adoption of those technologies. In the case of accessibility metadata, the technical difficulties are substantial. As explained in the section on metadata, there are many kinds of metadata and yet they share a goal of interoperability - essential if the adoption is to scale and essential if it is to be across-institutions, sectors, or otherwise working beyond the confines of a single environment. The problems related to interoperability are considered later (ch???) but they are not the only ones: metadata is frequently required to work well both locally and globally, meaning that it has to be useful in the local context and work across contexts. This tension between local and global is at the heart of the technical challenges when a bunch of diverse stakeholders are involved but so are the political and affective challenges - for adoption.

At the time the work was being undertaken, there was a major review of accessibility being undertaken by the ISO/IEC JTC1. A Special Working Group (SWG-A) was formed to do three things: to determine the needs of people with disabilities with respect to digital resources, to audit existing laws, regulations and standards that affect these, and to identify the gaps. For many, this exercise seemed like a commercial exercise to minimise the need for accessibility standards compliance, especially as when the author asked the information about the people represented in the Working Group, there were some remarkable revelations. As members of the group, the author and some others were very concerned that the meetings which were nominally open, were held three-monthly in expensive locations around the world. It was clear from the attendance that it was not easy for people with disabilities to attend and their representatives were unlikely to be able to afford to attend. Evidence for this was that there were almost no such people. When the author asked about the people who were present, specifically if they could identify their employers, it took an hour of debate before this was allowed and then it was revealed that most of the people in positions of influence in the group were employed by a single multi-national technology company although they could claim their involvement as representative of a range of countries. not only was there unease about the disproportionate commercial representation, but it emerged that the agenda was constantly under pressure to do more than the stated research work, and to try to influence the development of new regulations that were seen to threaten the major technology companies. Although heavy resistance to the 'commercial' interests was provided by others and in the end the work was limited in scope to the original proposals, it was interesting to see just how much effort is available from commercial interests when they want to protect their established practices. Given that many of the companies represented in the SWG-A are also participants in consortia such as W3C, IMS GLC, etc, it is indicative of what was potentially constraining of the AfA work of the author and others.

In design experiments, or research using design experiments that is often just called design research, it is a feature of the process that the goals and aspirations of those involved are considered and catered for. In fact, as the work evolves, the goals of the various parties are likely to be revisited as the work changes according to the circumstances and the research enlightens the design of the experiments. This research is not about researchers testing a hypothesis on a randomly selected group of subjects; the stakeholders and the designers interact regularly and advantage is taken of this to guide the design. The practical aspects are constantly revised according to newly emerging theoretical principles and the new practical aspects lead to revised theories. The goals do not change but the ways of achieving them are not held immutable.

In the work reported here, considerable interaction occurred between the author as researcher and the author and colleagues and other stakeholders in the development process. This was especially exemplified in the various voting procedures that moved the work through the relevant standards bodies. These formal processes take place at regular intervals and demand scrutiny of the work by a range of people and then votes of support for continued work. Challenges to the work, when they occur, generally promote the work in ways that lead to revisiting of decisions and revision of the theoretical position being relied upon at the time. Such challenges also provide insight for the researcher into the problems and solutions being proposed .

The development work reported has been progressively adopted and has now become part of the Australian standard for all public resources on the Web and by virtue of being an ISO standard, an educational standard for Australia. This can be taken as indication of it having proven satisfactory to a considerable number of people. Only actual implementation and use will prove it to have been truly successful because it will need to be proliferated to the extent that it becomes useful. Implementations are discussed further in Ch ???.

In particular, the author sat between two major metadata camps, as it were, working with IMS GLC and many whose experience was mainly with relational databases and LOM metadata, which is very hierarchical, and the DC community of 'flat' metadata users, given her role as Chair of the DC Accessibility Working Group (later the DC Accessibility Community) and membership of the Advisory Board of DCMI. This was, indeed, an uncomfortable position because the educational community who initially was driving the work is deeply engaged in the LOM approach, even though many others working in education are not. The former's interests were towards an outcome that would suit them but, as the author saw it, risk even further fragmentation of the total set of resources available to education, and so not serve the real goal which was to increase the accessibility of the Web (of resources).

DCMI itself was wrestling all that time with the problem of interoperability of the LOM and DC educational community's metadata, a difficulty that has been present since the first educational application profile was proposed nearly a decade ago. The interoperability is necessary given that, for example, government resources might be used in educational settings and if their metadata could not be cross-walked (see ch ???) from one scheme to the other, the descriptions of the government resources would not be useful to educationalists, which seems ridiculous. One way to ease the problem would have been to develop a standard that exactly suited both metadata systems, and that might have been possible, but there was insufficient technical expertise available to achieve that goal, so the best that could be done in the circumstances became the modified goal. This was achieved and it is possible to cross-walk between the various metadata standards so that it does not matter so much which is used, because the data of the metadata descriptions can be shared.

The following table of stakeholders will have a list of properties along the top and then ticks and it will show graphically how diverse they are.

| Participating Stakeholders | ||

|---|---|---|

| University of Toronto | Large university with history of inclusion not standards body but active participant in standards work TILE |

|

| WGBH/NCAM | Large media company commercial interests experts in accessibility of rich media SALT project specifically to work on AfA not standards body but active participant in standards work |

|

| IMS GLC | IMS processes Consortium of content producers and CMS educational context metadata? expertise in system development Expensive to join - closed processes LOM model

|

What do the LMS developers want? What do the content developers want? |

| DCMI | DC processes Consortium of anyone who's interested cross domain global metadata experts free participation DC Abstract model

|

|

| CEN-ISSS LTSC | CEN processes European education uncertain representation |

|

| ISO JTC1 SC36 | ISO processes national bodies fee paying membership |

|

| W3C WCAG | ||

| SA IT-19 ??? | ||