Site Navigation

Contents of Thesis ack'ments - Introduction - Context - Accessibility - W3C/WAI - LitReview - Metadata - Accessibility Metadata - PNP - DRD - Matching - UI profiles - Interoperability - Framework - Implementation - Conclusion - References - Appendix 1 - Appendix 2 - Appendix 3 - Appendix 4 - Appendix 5 - Appendix 6 - Appendix 7

In this chapter, there is first a brief introduction to the technical and organisational background in which the research took place, and then a discussion of the methodology adopted for the research. As will be seen, the context, to a large extent, determined the methodology, as is appropriate.

In 2004, Tim O'Reilly coined a term that has become a catch-cry far and wide. He recently said of it (2005):

The concept of "Web 2.0" began with a conference brainstorming session between O'Reilly and MediaLive International. Dale Dougherty, web pioneer and O'Reilly VP, noted that far from having "crashed", the web was more important than ever, with exciting new applications and sites popping up with surprising regularity. What's more, the companies that had survived the collapse seemed to have some things in common. Could it be that the dot-com collapse marked some kind of turning point for the web, such that a call to action such as "Web 2.0" might make sense? We agreed that it did, and so the Web 2.0 Conference was born.

In the year and a half since, the term "Web 2.0" has clearly taken hold, with more than 9.5 million citations in Google. But there's still a huge amount of disagreement about just what Web 2.0 means, with some people decrying it as a meaningless marketing buzzword, and others accepting it as the new conventional wisdom.

A significant aspect of the Web as envisioned is that it is a platform:

Like many important concepts, Web 2.0 doesn't have a hard boundary, but rather, a gravitational core. You can visualize Web 2.0 as a set of principles and practices that tie together a veritable solar system of sites that demonstrate some or all of those principles, at a varying distance from that core.

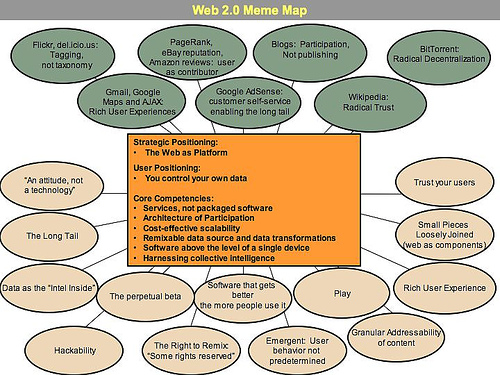

O'Reilly offered the following diagram from a brain-storming session to help others visualize this 'new' Web:

Many of the features depicted in this image are deployed in the proposed new framework for accessibility. The following, in particular, fit into this category:

In November 2005, Dan Saffer described Web 2.0:

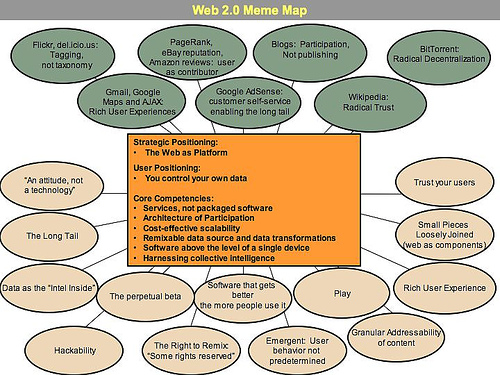

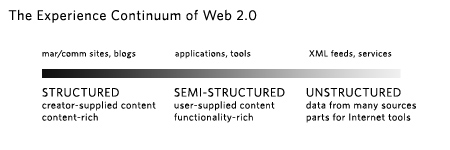

On the conservative side of this experience continuum, we'll still have familiar Websites, like blogs, homepages, marketing and communication sites, the big content providers (in one form or another), search engines, and so on. These are structured experiences. Their form and content are determined mainly by their designers and creators.

In the middle of the continuum, we'll have rich, desktop-like applications that have migrated to the Web, thanks to Ajax, Flex, Flash, Laszlo, and whatever else comes along. These will be traditional desktop applications like word processing, spreadsheets, and email. But the more interesting will be Internet-native, those built to take advantage of the strengths of the Internet: collective actions and data (e.g. Amazon's "People who bought this also bought..."), social communities across wide distances (Yahoo Groups), aggregation of many sources of data, near real-time access to timely data (stock quotes, news), and easy publishing of content from one to many (blogs, Flickr).

The experiences here in the middle of the continuum are semi-structured in that they specify the types of experiences you can have with them, but users supply the content (such as it is).

On the far side of the continuum are the unstructured experiences: a glut of new services, many of which won't have Websites to visit at all. We'll see loose collections of application parts, content, and data that don't exist anywhere really, yet can be located, used, reused, fixed, and remixed.

The content you'll search for and use might reside on an individual computer, a mobile phone, even traffic sensors along a remote highway. But you probably won't need to know where these loose bits live; your tools will know.

These unstructured bits won't be useful without the tools and the knowledge necessary to make sense of them, sort of how an HTML file doesn't make much sense without a browser to view it. Indeed, many of them will be inaccessible or hidden if you don't have the right tools. (Saffer, 2005)

As Saffer says,

There's been a lot of talk about the technology of Web 2.0, but only a little about the impact these technologies will have on user experience. Everyone wants to tell you what Web 2.0 means, but how will it feel? What will it be like for users?

The work reported here should give a sense of the changes at least in the realm of accessibility. One significant change being, hopefully, that what is done will make the Web more accessible to everyone, not that there will need to be special activities for some people.

These comments are made at a time when there is already talk of Web 3.0. This idea of versions of the Web is clearly abhorrent to some, as its continuous evolution is considered by them to be one of its virtues (Borland, 2007), but the significance of the changes in the Web are not denied. If Web 3.0 represents anything, according to Borland:

Web 1.0 refers to the first generation of the commercial Internet, dominated by content that was only marginally interactive. Web 2.0, characterized by features such as tagging, social networks, and user- created taxonomies of content called "folksonomies," added a new layer of interactivity, represented by sites such as Flickr, Del.icio.us, and Wikipedia.

Analysts, researchers, and pundits have subsequently argued over what, if anything, would deserve to be called "3.0." Definitions have ranged from widespread mobile broadband access to a Web full of on-demand software services. A much-read article in the New York Times last November clarified the debate, however. In it, John Markoff defined Web 3.0 as a set of technologies that offer efficient new ways to help computers organize and draw conclusions from online data, and that definition has since dominated discussions at conferences, on blogs, and among entrepreneurs. (Borland, 2007, page 1)

---------------------

While there are many organisations related to accessibility, too many to even name, there are some organisations that have played a significant role in shaping the Web since its inception. Some of these will be identified here as they usually also provide many online resources and any understanding of the 'literature' of accessibility of the Web or metadata relating to it necessarily relies on the work of these organisations.

W3C's approach has evolved over time but it is currently understood as promoting 'universal design'. This idea was fundamental to WCAG 1.0 and is maintained for the forthcoming (WCAG 2.0) guidelines for the creation of content for the Web. WCAG is complemented by guidelines for authoring tools that reinforce the principles in the content guidelines and W3C also offers guidelines for browser developers. Significantly, the guidelines are also implemented by W3C in its own work via the Protocols and Formats Working Group who monitor all W3C developments from an accessibility perspective.

W3C entered the accessibility field at the instigation of its director and especially the W3C lead for Society and Technology at the time, Professor James Miller, shortly after the Web started to take a significant place in the information world. W3C established a new activity known as the Web Accessibility initiative with funding from international sources. From the beginning, although W3C is essentially a members' consortium, in the case of the WAI, all activities are undertaken openly (all mailing lists etc are open to the public all the time) and experts depend upon input from many sources for their work.

The W3C/WAI activity has done more than develop standards over the years through its fairly aggressive outreach program. It publishes a range of materials that aim to help those concerned with accessibility to work on accessibility in their context.

The Trace Research & Development Center is a part of the College of Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Founded in 1971, Trace has been a pioneer in the field of technology and disability.

Trace Center Mission Statement:

To prevent the barriers and capitalize on the opportunities presented by current and emerging information and telecommunication technologies, in order to create a world that is as accessible and usable as possible for as many people as possible. ...

Trace developed the first set of accessibility guidelines for Web content, as well as the Unified Web Access Guidelines, which became the basis for the World Wide Web Consortium's Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 1.0 [TRACE].

Wendy Chisholm, who originally worked at TRACE was, for many years, a leading staff member of WAI and author of a number of the accessibility guidelines and other documents.

The Adaptive Technology Resource Centre is at the University of Toronto. It advances information technology that is accessible to all through research, development, education, proactive design consultation and direct service. The Director of ATRC, Professor Jutta Treviranus, has been significant in the standards work in many fora and the group has contributed the main work on the ATAG. They are also largely responsible for initiating the work for the AccessForAll approach to accessibility and the technical development associated with it.

The Carl and Ruth Shapiro Family National Center for Accessible Media is part of the WGBH, one of the bigger public broadcast media companies in the USA. Henry Becton, Jr., President of WGBH, is quoted on the WGBH Web site as saying that:

WGBH productions are seen and heard across the United States and Canada. In fact, we produce more of the PBS prime-time and Web lineup than any other station. Home video and podcasts, teaching tools for schools and home-schooling, services for people with hearing or vision impairments ... we're always looking for new ways to serve you! (WGBH About, 2007)

With respect to people with disabilities, the site offers the following:

People who are deaf, hard-of-hearing, blind, or visually impaired like to watch television as much as anyone else. It just wasn't all that useful for them ... until WGBH invented TV captioning and video descriptions.

Public television was first to open these doors. WGBH is working to bring media access to all of television, as well as to the Web, movie theaters, and more (WGBH Access, 2007).

NCAM is a major vehicle for these activities within the media context and its Research Director, Madeleine Rothberg, has been a significant researcher and author in the work that supports AccessForAll in a range of such contexts.

In addition to organisations that have been involved in the research and development that have led to the AccessForAll approach and standards, there have been the standards bodies themselves that have published standards but also initiated work that has made the standards' development possible. In many cases, standards are determined by 'standards' bodies which are, as in the case of the International Organisation for Standardization [ISO], federations of bodies that ultimately have the power to make laws with respect to the specifications.

W3C's role in the standards world is often described as different from, say, the role of ISO because of the structure of the organisation and also the processes used to develop specifications for recommendation (de facto standards). W3C membership is open to any organisation and tiered so that larger more financial organisations contribute a lot more funding than smaller or not-for-profit ones. The work processes are defined by the W3C so that working groups are open and consult widely and prepare documents which are voted on by members and then recommended, or otherwise, by the Director of the W3C, Sir Tim Berners-Lee. They are published as recommendations but usually referred to as standards and certainly, in the case of the accessibility guidelines, are de facto standards.

ISO collaborates with its partners, the International Electrotechnical Commission [IEC] and the International Telecommunication Union [ITU-T], particularly in the field of information and communication technology international standardization.

ISO makes clear on their Web site, that it is

a global network that identifies what International Standards are required by business, government and society, develops them in partnership with the sectors that will put them to use, adopts them by transparent procedures based on national input and delivers them to be implemented worldwide (ISO in brief, 2006).

ISO federates 157 national standards bodies from around the world. ISO members appoint national delegations to standards committees. In all, there are some 50,000 experts contributing annually to the work of the Organization. When ISO International Standards are published, they are available to be adopted as national standards by ISO members and translated.

The Joint Technical Committee 1 of ISO is for standardization in the field of information technology. At the beginning of April 2007, it had 2068 published ISO standards related to the TC and its SCs; 2068; 538 published ISO standards under its direct responsibility; 31 participating countries; 44 observer countries; at least 14 other ISO and IEC committees and at least 22 international organizations in liaison (JTC1, 2007). JTC1 SC36 WG7 is the working group for Culture, language and human-functioning activities within the Sub-Committee 36 for IT for Learning Education and Training. it is this working group that has developed the AccessForAll All standards for ISO. Co-editors for these standards come from Australia (Liddy Nevile), Canada (Jutta Treviranus) and the United Kingdom (Andy Heath), but there have been major contributions from others in the form of reviews, suggestions, and discussion and support.

The IMS Global Learning Consortium [IMS] describes itself as having more than 50 Contributing Members and affiliates from every sector of the global learning community. They include hardware and software vendors, educational institutions, publishers, government agencies, systems integrators, multimedia content providers, and other consortia. IMS claims to provide "a neutral forum in which members work together to advocate the use of technology to support and transform education and learning" (IMS, 2007).

A joint project between WGBH/NCAM and IMS initiated the work on AccessForAll with a Specifications for Accessible Learning Technologies Grant in December 2000. Anastasia Cheetham, Andy Heath, Jutta Treviranus, Liddy Nevile, Madeleine Rothberg, Martyn Cooper and David Wienkauf were particularly significant in this work.

The Web site describes the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative as

an open organization engaged in the development of interoperable online metadata standards that support a broad range of purposes and business models. DCMI's activities include work on architecture and modeling, discussions and collaborative work in DCMI Communities and DCMI Task Groups, annual conferences and workshops, standards liaison, and educational efforts to promote widespread acceptance of metadata standards and practices (DCMI, 2007).

The DCMI Accessibility Community has been working formally on Dublin Core metadata for accessibility purposes since 2001. While the early work focused on how metadata might be used to make explicit the characteristics of resources as they related to the W3C WCAG, this goal has been realised in the AccessForAll work. The DCMI Accessibility Community has been working in close collaboration with the IMS and ISO efforts but it has engaged the metadata community, and therefore those working primarily in a wider context than education, especially including government and libraries.

The European Committee for Standardization, was founded in 1961 by the national standards bodies in the European Economic Community and European Free Trade Association countries. CEN is a forum for the development of voluntary technical standards to promote free trade, the safety of workers and consumers, interoperability of networks, environmental protection, exploitation of research and development programmes, and public procurement (CEN, 2007).

A number of CEN committees have been involved in the development of AccessForAll, either in the form of contributed funding as for the MMI-DC, or in their independent review of the development of AccessForAll and how it will work in their context if it is adopted by the other standards bodies. Significant in this work have been Andy heath, Liddy Nevile, Martyn Cooper and Martin Ford who have all worked on CEN projects in recent years. the context for this work has included but not been limited to education.

There are a number of other standards bodies or regional associations that have considered the work in depth and contributed in some way. In fact, in early 2007, IMS versions of the specifications had been downloaded 28,082 times and the related guidelines more than 176,505 times. (Rothberg, 2007) CanCore has published the CanCore Guidelines for the "Access for All" Digital Resource Description Metadata Elements (Friesen, 2006) following an interview with Jutta Treviranus in which she discusses the specifications (Friesen, 2005).

The Centre for Educational Technology and Interoperability Standards [CETIS] in the UK provides a national research and development service to UK Higher and Post-16 Education sectors, funded by the Joint Information Systems Committee. CETIS has published some summary documents about the IMS AccMD, IMS AccLIP and IMS Guidelines.

The research reported is not a traditional empirical study of an existing situation.

John Seely Brown (1998) liked to differentiate between what he thought of as two main kinds of research, sustaining and pioneering. Sustaining research, he thought, is aimed at analysis and evaluation of existing conditions. The problem for researchers in fast-changing fields is that often, by the time sustaining research is reported, the circumstances have changed. As the original circumstances cannot be reproduced, the research results would need to be interpreted into a different context to be useful and in some fields, this cannot happen. In the case of pioneering research, the work is successfully implemented or, perhaps more often, forgotten. This is the sort of work that many technology researchers are engaged in: they follow what are traditional research practices to a point, but their work is evaluated differently and they need to engage with and accept different types of evaluation. We all know that the 'best' technology is not always the one that becomes the accepted technology. In the current technology environment, acceptance is crucial because it is the mass acceptance and use that makes the technology what it is. In the case of metadata, without mass acceptance there is nothing of particular value.

It has taken ten years of trial for Dublin Core metadata to become 'de rigueur': for many years it was not clear what sort of metadata would become the assumed standard, regardless of what was best or meant to take precedence, or even if metadata would continue to be used. In Australia, the UK, Canada and more than twenty other countries, DC metadata is recommended now for all government and other public resources on the Web (ref).

Pioneering research is what Seely Brown argued was the main output, and the valued output, from Xerox Parc in the 1980's. Staff at that institution developed some of the most significant ideas that have been incorporated into computers over the last 25 years. They were researchers but also inventors - people who had to know the needs, the problems, the context, et cetera and then invent something that might be useful. Their work has been tested not by an evaluation of their research methodologies, or how closely they followed the methodology they adopted, but rather by how useful and effective their work has become.

Within the field of pharmacology, research is combined with empirical research before the work is released onto the market or used with humans. In the case of developments of Web 2.0, a product or idea or standard's release is watched for adoption and it is only in hindsight that its intrinsic value is determined.

Despite the interest in the idea of what became AccessForAll metadata, there was a substantial need for considerable sustaining research work to create a suitable awareness of the context for the work and the value of the work. This involved developing a strong understanding of the theoretical and practical issues related to accessibility, including practical considerations to do with professional development of resource developers and system developers, and the administrative processes and people that usually determine what these developers will be funded to do. It also involved the reading and writing of critical reviews of other work. In particular, while there was little doubt of the potential benefit to users with disabilities, it was not at all clear how to work with the prototyped ideas to make them mainstream in the wider world, both in the world outside the educational domain and in the world of mixed metadata schemas.

Although already the metadata profiles have begun to emerge, and the framework is being used to extend the situations in which AfA can be useful, there is more work to be done in developing ways to enable distributed discovery of suitable accessible resource components for users and also to build the architecture that can take maximum advantage of the AfA approach. Both of these developments are outside the scope of this present work but they, too, are explained by, and therefore in some ways enabled by, the 'sustaining' research that is reported here.

The development work reported is often characterised as that without regard for the processes involved in achieving it. One is reminded of the story of Alexandra whose project to build a marble-machine was rejected as not scientific until the process was carefully examined and she was ultimately awarded a first prize for the best science project (Resnick, 2006). In some fields, research is not just about writing a report, it is also about repeatedly designing, creating, testing, evaluating and reviewing something in an iterative process, often towards an unknown result but according to a set of goals. Such processes benefit from rigorous scrutiny which can be attracted in a variety of ways, including by being undertaken in a context where there are strong stakeholders with highly motivated interests to protect.

In order to investigate how accessibility was working at a local and specific location, the author worked with several colleagues to audit the La Trobe University Web site. The results were submitted under a contract to the University and also in a session at the 2003 OZeWAI Conference. They were considered in a paper presented at the DC 2004 Conference (Nevile, 2004). The process was significantly eased by the combination of several available tools and produced metadata about all 48,084 pages reviewed. The tools could have been adapted to produce almost all of the metadata referred to below as AccessForAll metadata.

The Accessible Content Development Web site (Nevile1) was built in an effort to understand who might need to do what, how they might understand their roles, and what technical assistance they could receive. The aim was to provide a fast look-up site accessible by topic and focus, rather than the lengthy, integrated approaches required at the time by anyone using the W3C Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). Having been built, this site was given over to the La Trobe University who were supposed to maintain it. In the event, it was not maintained and it is now significantly outdated. The work involved extensive research including reviewing the literature and test ideas discovered from it, matched against the specifications from W3C and elsewhere, and experiments to design and create solutions.

For a major Braille project associated with the Accessible Content Development Web site, the first task was to understand the problems, then to see what partial solutions were available, and then to develop a prototype service to convert mathematics texts to Braille. In the last case, there was no need to survey anyone to determine the size of the problem or the satisfaction available from existing solutions - the picture was patently bleak for the few Braille users interested in mathematics and, in particular, the text was required by a Melbourne University student for his study program (ref). Ultimately, the research was grounded in computer science, where it is common to have a prototype as the outcome with an accompanying document that explains the theoretical aspects and implications of the prototype. In this case, the prototype work was undertaken by a student who was supervised by the author, who managed or personally did much of the other work in the project (Munro, 2007, etc???).

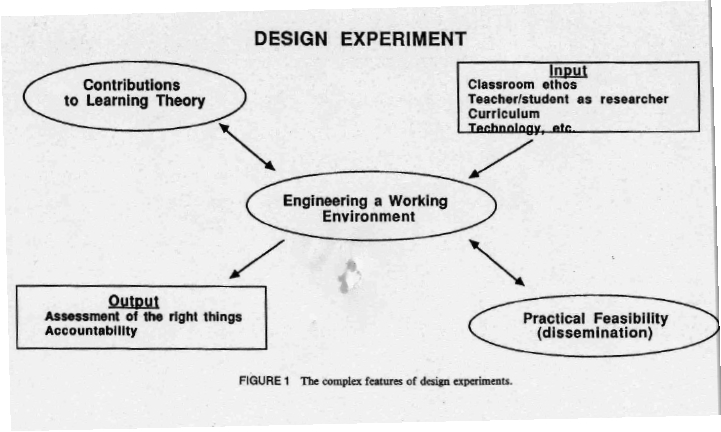

In "Design Experiments: Theoretical and Methodological Challenges in Creating Complex Interventions in Classroom Settings", Ann Brown (1992) describes the problem of undertaking research in a dynamic classroom. She was, at the time, already an accomplished experimental researcher, but argued that it was not possible or appropriate to undertake experimental research in a changing classroom. "In the classroom and in the laboratory, I attempt to engineer interventions that not only work by recognizable standards but are also based on theoretical descriptions that delineate why they work, and thus render them reliable and repeatable" (p. 2). Brown argued that the circumstances necessitated the development of methodologies that would usefully analyse what was happening in the changing classrooms and provide useful information for others wishing to replicate the model and results in other classrooms.

(Note: this image (Figure 1) appears in the online version of the paper by Ann Brown and may not have been in the original or may have been modified after the book was published.)

Others have since further refined the methodology of design research, in the process elaborating other contexts in which it may be applied. "Design experiments have both a pragmatic bent—"engineering" particular forms of learning—and a theoretical orientation—developing domain-specific theories by systematically studying those forms of learning and the means of supporting them" (Cobb, P., J. Confrey, et al., 2003).

In "Design-based research: An emerging paradigm for educational inquiry",

The authors argue that design-based research, which blends empirical educational research with the theory-driven design of learning environments, is an important methodology for understanding how, when, and why educational innovations work in practice. Design-based researchers’ innovations embody specific theoretical claims about teaching and learning, and help us understand the relationships among educational theory, designed artifact, and practice. Design is central in efforts to foster learning, create usable knowledge, and advance theories of learning and teaching in complex settings. Design-based research also may contribute to the growth of human capacity for subsequent educational reform (DBRC and D.-B. R. Collective, 2003).

The complexity of the accessibility work is not unlike that of a classroom. Everything is constantly changing, including the technology, the skills and practices of developers, the jurisdictional contexts in which accessibility is involved and the laws governing it within those contexts, and the political environment in which people are making decisions about how to implement, or otherwise, accessibility. There are also a number of players, all of whom have different agendas, priorities and constraints, despite their shared interest in increasing the accessibility of the Web for all.

The list of standards bodies and stakeholders (below), shows some of the major players and their interests in the work that was being undertaken. All of these stakeholders had to be won over as there is really no other way that technologies such as metadata schemas proliferate on the Web, and if they don't the technologies are not useful, as explained above. 'Winning over' bodies that use technologies often means providing a strong technical solution as well as compelling (in their eyes) reasons for adoption of those technologies. In the case of accessibility metadata, the technical difficulties are substantial. As explained in the section on metadata, there are many kinds of metadata and yet they share a goal of interoperability - essential if the adoption is to scale and essential if it is to be across-institutions, sectors, or otherwise working beyond the confines of a single environment. The problems related to interoperability are considered later (ch???) but they are not the only ones: metadata is frequently required to work well both locally and globally, meaning that it has to be useful in the local context and work across contexts. This tension between local and global is at the heart of the technical challenges when a bunch of diverse stakeholders are involved but so are the political and affective challenges - for adoption.

At the time the work was being undertaken, there was a major review of accessibility being undertaken by the ISO/IEC JTC1. A Special Working Group (SWG-A) was formed to do three things: to determine the needs of people with disabilities with respect to digital resources, to audit existing laws, regulations and standards that affect these, and to identify the gaps. For many, this exercise seemed like a commercial exercise to minimise the need for accessibility standards compliance, especially as when the author asked the information about the people represented in the Working Group, there were some remarkable revelations. As members of the group, the author and some others were very concerned that the meetings which were nominally open, were held three-monthly in expensive locations around the world. It was clear from the attendance that it was not easy for people with disabilities to attend and their representatives were unlikely to be able to afford to attend. Evidence for this was that there were almost no such people. When the author asked about the people who were present, specifically if they could identify their employers, it took an hour of debate before this was allowed and then it was revealed that most of the people in positions of influence in the group were employed by a single multi-national technology company although they could claim their involvement as representative of a range of countries. not only was there unease about the disproportionate commercial representation, but it emerged that the agenda was constantly under pressure to do more than the stated research work, and to try to influence the development of new regulations that were seen to threaten the major technology companies. Although heavy resistance to the 'commercial' interests was provided by others and in the end the work was limited in scope to the original proposals, it was interesting to see just how much effort is available from commercial interests when they want to protect their established practices. Given that many of the companies represented in the SWG-A are also participants in consortia such as W3C, IMS GLC, etc, it is indicative of what was potentially constraining of the AfA work of the author and others.

In design experiments, or research using design experiments that is often just called design research, it is a feature of the process that the goals and aspirations of those involved are considered and catered for. In fact, as the work evolves, the goals of the various parties are likely to be revisited as the work changes according to the circumstances and the research enlightens the design of the experiments. This research is not about researchers testing a hypothesis on a randomly selected group of subjects; the stakeholders and the designers interact regularly and advantage is taken of this to guide the design. The practical aspects are constantly revised according to newly emerging theoretical principles and the new practical aspects lead to revised theories. The goals do not change but the ways of achieving them are not held immutable.

In the work reported here, considerable interaction occurred between the researcher and colleagues and the other stakeholders. This was especially exemplified in the various voting procedures that moved the work through the relevant standards bodies. These formal processes take place at regular intervals and demand scrutiny of the work by a range of people and then votes of support for continued work. Challenges to the work, when they occur, generally promote the work in ways that lead to revisiting of decisions and revision of the theoretical position being relied upon at the time.

The work reported has been progressively adopted and has now become part of the Australian standard for all public resources on the Web and by virtue of being an ISO standard, an educational standard for Australia. This can be taken as indication of it having proven satisfactory to a considerable number of people at the documentary level. Only actual implementation and use will prove it to have been truly successful because it will need to be proliferated to the extent that it becomes useful. Implementations are discussed further in Ch ???.

In particular, the author sat between two major metadata camps, as it were, working with IMS GLC and many whose experience was mainly with relational databases and LOM metadata, which is very hierarchical, and the DC community of 'flat' metadata users, given her role as Chair of the DC Accessibility Working Group (later the DC Accessibility Community) and membership of the Advisory Board of DCMI. This was, indeed, an uncomfortable position because the educational community who initially was driving the work is deeply engaged in the LOM approach, even though many others working in education are not. The former's interests were towards an outcome that would suit them but, as the author saw it, risk even further fragmentation of the total set of resources available to education, and so not serve the real goal which was to increase the accessibility of the Web (of resources).

DCMI itself was wrestling all that time with the problem of interoperability of the LOM and DC educational community's metadata, a difficulty that has been present since the first educational application profile was proposed nearly a decade ago. The interoperability is necessary given that, for example, government resources might be used in educational settings and if their metadata could not be cross-walked (see ch ???) from one scheme to the other, the descriptions of the government resources would not be useful to educationalists, which seems ridiculous. One way to ease the problem would have been to develop a standard that exactly suited both metadata systems, and that might have been possible, but there was insufficient technical expertise available to achieve that goal, so the best that could be done in the circumstances became the modified goal. This was achieved and it is possible to cross-walk between the various metadata standards so that it does not matter so much which is used, because the data of the metadata descriptions can be shared.

The following table of stakeholders will have a list of properties along the top and then ticks and it will show graphically how diverse they are.

| Participating Stakeholders | ||

|---|---|---|

| University of Toronto | Large university with history of inclusion not standards body but active participant in standards work TILE |

|

| WGBH/NCAM | Large media company commercial interests experts in accessibility of rich media SALT project specifically to work on AfA not standards body but active participant in standards work |

|

| IMS GLC | IMS processes Consortium of content producers and CMS educational context metadata? expertise in system development Expensive to join - closed processes LOM model

|

What do the LMS developers want? What do the content developers want? |

| DCMI | DC processes Consortium of anyone who's interested cross domain global metadata experts free participation DC Abstract model

|

|

| CEN-ISSS LTSC | CEN processes European education uncertain representation |

|

| ISO JTC1 SC36 | ISO processes national bodies fee paying membership |

|

| W3C WCAG | ||

| SA IT-19 ??? | ||