Site Navigation

Contents of Thesis ack'ments - Preamble - Introduction -Accessibility - W3C/WAI - LitReview - Metadata - Accessibility Metadata - PNP - DRD - Matching - UI profiles - Interoperability - Framework - Implementation - Conclusion - References - Appendix 1 - Appendix 2 - Appendix 3 - Appendix 4 - Appendix 5 - Appendix 6 - Appendix 7

This chapter reviews relevant literature and activities in order to locate AccessForAll work within the appropriate context.

The AccessforAll framework brings together two worlds of intellectual endeavour - accessibility work and metadata work. In both domains, there have been previous models and approaches on which the current work builds. Given the significance and complexity of both accessibility and metadata work, these concepts will be described and discussed in detail. In this chapter, there is a brief introduction only in order to make sense of the chapter. The focus will be an introduction to and critical discussion of the role of the previous models and frameworks and the context in which they are operating.

The sections are:

For many years, Microsoft showed its skepticism for universal accessibility including by its lack of effort to make its Internet Explorer browser UAAG conformant. In 2003, however, Microsoft commissioned a study in the US to get some indication of who might be needing assistance with accessing information if they are to try using computers or other electronic devices. The overall population in the US in the age range 18 to 64 years was found to be divided into the following four groups: those with severe, mild, minimal and no difficulties, in the following proportions: 25% with severe, 37% with mild, and 37% with minimal or no difficulties resulting from disabilities.

Further, they found that:

Visual, dexterity, and hearing difficulties and impairments are the most common types of difficulties or impairments among working-age adults:

• Approximately one in four (27%) have a visual difficulty or impairment.

• One in four (26%) have a dexterity difficulty or impairment.

• One in five (21%) have a hearing difficulty or impairment.Somewhat fewer working-age adults have a cognitive difficulty or impairment (20%) and very few (4%) have a speech difficulty or impairment.

... For the top three difficulties and impairments:

• 16% (27.4 million) of working-age adults have a mild visual difficulty or impairment, and 11% (18.5 million) of working-age adults have a severe visual difficulty or impairment.

• 19% (31.7 million) of working-age adults have a mild dexterity difficulty or impairment, and 7% (12.0 million) of working-age adults have a severe dexterity difficulty or impairment.

• 19% (32.0 million) of working-age adults have a mild hearing difficulty or impairment, and 3% (4.3 million) of working-age adults have a severe hearing difficulty or impairment (Microsoft, 2003b).

or as shown:

These findings show that the majority of working-age adults are likely to benefit from the use of accessible technology. As shown in the chart in Figure 3, 60% (101.4 million) of working-age adults are likely or very likely to benefit from the use of accessible technology.

The chart in Figure 3 also shows the percentages of working-age adults who are likely or very likely to benefit from the use of accessible technology due to a range of mild to severe difficulties and impairments:

• 38% (64.2 million) of working-age adults are likely to benefit from the use of accessible technology due to a mild difficulties and impairments.

• 22% (37.2 million) of working-age adults are very likely to benefit from the use of accessible technology due to a severe difficulties and impairments.

• 40% (67.6 million) of working-age adults are not likely to benefit due to a no or minimal difficulties or impairments (Microsoft, 2003b).

or as shown:

The report states:

The fact that a large percentage of working-age adults have difficulties or impairments of varying degrees may surprise many people. However, this study uniquely identifies individuals who are not measured in other studies as "disabled" but who do experience difficulty in performing daily tasks and could benefit from the use of accessible technology.

Note that many or most of the individuals who have mild difficulties and impairments do not self-identify as having an impairment or disability. In fact, the difficulties they have are not likely to be noticeable to many of their colleagues. (Microsoft, 2003b)

Three more sets of figures provide the incentive to think carefully about accessibility in the general population:

and

combined with

paint a picture for the US that looks grim. There is clearly a worrying trend towards much higher proportions of the community being much older than at present, and therefore more likely at risk of disability. There is every reason to assume the figures will be similar in Australia.

In summary, the Microsoft report claims:

In the United States, 60% (101.4 million) of working-age adults who range from 18 to 64 years old are likely or very likely to benefit from the use of accessible technology due to difficulties and impairments that may impact computer use. Among current US computer users who range from 18 to 64 years old, 57% (74.2 million) are likely or very likely to benefit from the use of accessible technology due to difficulties and impairments that may impact computer use. (Microsoft, 2003d)

This points to the fact that not all those who could benefit from computer use, in fact do use computers. There are many reasons for this, but as the trend to publish becomes electronic and the younger people adopt the technology, there is clearly going to be an increasing problem unless accessibility is also rapidly increased.

While Microsoft was working to convince, or otherwise, itself of the need to pay attention to accessibility issues, Texthelp Systems Inc. has a different slant because they have developed a solution at least for a high proportion of those with disabilities. They claim:

In the US and Canada there are:

45+ million people with literacy problems (source :U.S. Nat'l Literacy Survey 1992)

10-15% of the population with a learning disability (source: National Institutes of Health)

18% of the population over age 5 for whom English is a second language (US Census Bureau 2002)

13+% of children aged 3-21 who receive special education (source: www.nces.ed.gov)

12% of the Canadian population with some type of disability (source: Statistics Canada)

22% of Canadians who are functioning at the lowest literacy level (source: Statistics Canada)

(BrowseAloud)

as justification for their product BrowseAloud. BrowseAloud is a service that can be offered by a web site to provide streamed reading aloud of the content of the site, assuming it is properly constructed.

In 2006, the US National Council on Disability released a policy paper that explores key trends in information and communication technology, highlights the potential opportunities and problems these trends present for people with disabilities, and suggests some strategies to maximize opportunities and avoid potential problems and barriers. In particular,

The following are some emerging technology trends that are causing accessibility problems.

The report points out that technologies in common use change fast and unpredictably with the result that "assistive technology developers cannot keep pace". They cite convergence and competitive differences as having "a negative effect on interoperability between AT and mainstream technology where standards and requirements are often weak or nonexistent". The rapid increase in the number of aging people who have naturally increasing disabilities is, of course, always a concern.

On a more positive note, the NCD report summary lists a number of technological advances and says:

These technical advances will provide a number of opportunities for improvement in the daily lives of individuals with disabilities, including work, education, travel, entertainment, healthcare, and independent living.

It is becoming much easier to make mainstream products more accessible. The increasing flexibility and adaptability that technology advances bring to mainstream products will make it more practical and cost effective to build accessibility directly into these products, often in ways that increase their mass market appeal. (NCD, 2006)

In 1998, the US Federal Government legislated in favour of accessibility of digital resources including applications when the US federal government is procuring content, systems or services [s508]. As the largest employer of people with disabilities in the US, the Federal Government is also responsible for social security (income replacement) including for people with disabilities. There may have been some connection between the two because it is clearly better in a number of ways for the US Federal Government to offer useful employment to their citizens with disabilities than to have to support them all on disability pensions.

Fairfax in Australia, however, has perhaps offered a similarly striking economic reason for being concerned about accessibility. In 2003, they redeveloped their Web site with accessibility in mind and the result is a saving of an estimated $1,000,000 per year in transmission costs.

In a 2004 presentation for the Web Standards Group [WSG], Brett Jackson, Creative Director of Fairfax Digital, reported that Fairfax achieved more than the following success with a major move to the XHTML/CSS platform.

Who we are

- Fairfax Digital

- 40 sites

- 5 or 6 key destinations

- smh.com.au, theage.com.au, drive.com.au, mycareer.com.au, domain.com.au, afr.com.au

- SMH/AGE

- 135 million PI's per month

- 6 mill uv's

- The leading News sites in Australia

- 3 to 4 minute average session times

What we did

- moved our biggest sites across in a 6 month timeframe

- the smoothest rollout we have ever experienced

- will save a million $ in bandwidth a year

Where we're at now

- First major AUS publisher to make the move to CSS/xhtml

- started publishing in css/xhtml in nov 2003

- will move all sites across in the next 6-9 month (Jackson, 2004)

In 2003, a surprisingly high proportion of the Webby award winners (organised by the International Academy of Digital Arts and Sciences) were found to have accessible sites despite their multimedia attraction. In the opinion of Bob Regan, the accessibility expert for Macromedia, the vendors of DreamWeaver and Authorware, the Webby winners did not have accessible sites so much because they were concerned about accessibility as because they were concerned to use the latest, smartest techniques, and these inevitably led to increased accessibility (Regan, 2004).

The Authoring Tools Accessibility Guidelines [ATAG] can be used as functional requirements for the accessibility of authoring tools of all kinds. The underlying belief is that if the tools are designed so as to promote accessible products, inadvertently, simply by using the tools, authors of resources will make their products accessible. The author, involved in the development of ATAG, asserts that, in fact, if those who are so concerned about training their authors about accessibility were to save the money and time involved and instead buy them better authoring tools, more might be achieved with the same amount of money.

About 15% of Europeans report difficulties performing daily life activities due to some form of disability. With the demographic change towards an ageing population, this figure will significantly increase in the coming years. Older people are often confronted with multiple minor disabilities which can prevent them from enjoying the benefits that technology offers. As a result, people with disabilities are one of the largest groups at risk of exclusion within the Information Society in Europe.

It is estimated that only 10% of persons over 65 years of age use internet compared with 65% of people aged between 16-24. This restricts their possibilities of buying cheaper products, booking trips on line or having access to relevant information, including social and health services. Furthermore, accessibility barriers in products and devices prevents older people and people with disabilities from fully enjoying digital TV, using mobile phones and accessing remote services having a direct impact in the quality of their daily lives.

Moreover, the employment rate of people with disabilities is 20% lower than the average population. Accessible technologies can play a key role in improving this situation, making the difference for individuals with disabilities between being unemployed and enjoying full employment between being a tax payer or recipient of social benefits.

The recent United Nations convention on the rights of people with disabilities clearly states that accessibility is a matter of human rights. In the 21st century, it will be increasingly difficult to conceive of achieving rights of access to education, employment health care and equal opportunities without ensuring accessible technology (Reding, 2007).

There is no sense in which one would want to 'fault' the work of WAI in the area of accessibility. Like others, they have struggled to deal with an enormous and growing problem and everyone has contributed all they can to help the cause. Nevertheless, it is clear that the work of WAI alone cannot make the Web accessible. Although there has been a lot written about the achievements of the universal access approach, that is not the topic but rather the context for the current work, and working to increase its effectiveness is a major goal.

On 27/3/03, the UK Disabilities Rights Commission [DRC] issued a press release announcing its "First DRC Formal Investigation to focus on web access". They planned to investigate 1000 Web sites "for their ability to be accessed by Britain’s 8.5 million disabled people". They said that "A key aim of the investigation will be to identify recurrent barriers to web access and to help site owners and developers recognise and avoid them."

Significantly, this testing would not just be done by people evaluating the Web sites against a set of specifications, but they would also involve 50 disabled people in in-depth testing of a representative sample of the sites, testing in their case for practical usability. They claimed that "This work will help clarify the relationship between a site’s compliance with standards and its practical usability for disabled people." Bert Massie, Chairman of the DRC, said: “The DRC wants to see a society where all disabled people can participate fully as equal citizens and this formal investigation into web accessibility is an important step towards that goal.”

The DRC has legal power. As Mr Massie said: “Organisations which offer goods and services on the web already have a legal duty to make their sites accessible. The DRC is committed to enforcing these obligations but it is also determined to help site owners and developers tackle the barriers to inclusive web design.” (DRC, 2003)

On 30 April 2003, Accessify carried the following report on the briefing for the DRC project:

I had always thought that despite being labelled a 'formal' investigation, it would not carry any real legal implications, and thankfully (for many people) this was indeed the case. The term formal means that the DRC can carry out two types of investigation - a named party or a general investigation, and it's the latter that's taking place (a named party investigation would only apply to an organisation that is repeatedly 'offending' and is put under investigation). ...

So, it isn't a 'naming and shaming' exercise. What exactly does it entail then? Well, the format is basically this - 1,000 web sites hosted in Great Britain are going to be tested using automated testing tools such as Bobby and LIFT. From that initial 1,000 a further 100 sites will undergo more rigorous testing with the help of 50 people with a varying range of disabilities, varying technical knowledge and all kinds of assistive devices. This is not going to be centralised, so it will be interesting to see how the consistency is maintained. However, some of the testing will be filmed (the usual usability kind of set-up) and a whole raft of data is going to need to be pulled together in some kind of presentable format. I don't envy Helen Petrie who has the task of co-ordinating this!

The aim is to go beyond the simple testing for accessibility (although those original 1,000 sites will only have the automated tests) - the notion put forward is "Accessibility for Usability" ... which to these ears sounds like another term for 'Universal Design' or 'Design For All'. I'm not sure I appreciate the differences, if indeed there are any. It's certainly true that getting a Bobby Level AAA pass does not automatically make your site accessible, and it certainly doesn't assure usability. The interesting thing about this study, in my opinion, is how clear the correlation is between sites that pass the automated Bobby tests and their actual usability as determined by the testers. Will a site that has passed the tests with flying colours be more usable? I suspect that the answer will usually be yes. After all, if you have taken time and effort to make a site accessible, the chances are you have a good idea about the usability aspect. We will see ... (Accessify, 2003a)

Beyond establishing the proposed methodology, the DRC project leader claimed that they would:

Develop concept of “Accessibility for Usability” (Accessify, 2003b)

A year later, after the report was released, OUT-Law published an article about it (2004):

Egg.com and Oxfam.org.uk were among just five websites praised for their excellent accessibility...

City University London tested 1,000 UK-based sites on behalf of the DRC... Its findings, released yesterday, confirmed what many already suspected: very few sites are accessible to the disabled – albeit an inaccessible site presents a risk of legal action under the UK's Disability Discrimination Act.

However, while the report did not "name and shame" the 808 sites that failed to reach a minimum standard of accessibility in automated tests, City University has today revealed five "examples of excellence" from its study:

Helen Petrie, Professor of Human Computer Interaction Design at City University, said: “The Spinal Injuries Scotland site highlights how an accessible website can be created on a small budget and still be lively and colourful. Additionally, Egg’s site shows larger firms can embrace accessibility without compromising their corporate image or losing any sophistication from their e-services.”

Despite these examples of excellence, the overwhelming majority of websites were difficult, and at times impossible, for people with disabilities to access.

Petrie added: “Web developers need to use the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) guidelines as well as involve disabled users to ensure web sites are usable for these groups.” ...

In its automated tests, City University checked for technical compliance with the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) guidelines. ...

Following the report from the DRC, co-written by City University, the W3C issued a statement "to address potential misunderstandings about W3C's [Web Accessibility Initiative or WAI] Guidelines introduced by certain interpretations of the data."

This was not, however, a rejection of the DRC's study. In fact, the W3C has confirmed that it welcomes the UK research. The potential misunderstanding came from the fact that, while 1,000 sites underwent automated tests, City University put 100 of these sites to further testing by a disabled user group.

That group identified 585 accessibility and usability problems; but the DRC commented that 45 per cent of these were not violations of any of the 65 checkpoints listed in the W3C's Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, or WCAG.

The report was based on Version 1.0 of the WCAG – a version which has been around since 1999. The W3C was keen to point out that the WCAG is only one of three sets of accessibility guidelines recognised as international standards, all prepared under the auspices of the W3C's Web Accessibility Initiative. ...

The W3C explained that in fact its WAI package addresses 95 per cent of the problems highlighted by the DRC report. However, both the W3C and the DRC are keen to point out that they are working towards a common goal: to make websites more accessible to the disabled.

User testing

OUT-LAW spoke to Judy Brewer, the W3C's Web Accessibility Initiative Domain Leader. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines Working Group is currently working on Version 2.0 of the WCAG which she hopes will be finalised next year, possibly in the first quarter.

"We will be looking at the comments from the DRC report in our work on Version 2.0," explained Brewer. "We have always said that user testing of accessibility features is important when conducting comprehensive testing of web site accessibility."

She acknowledged that the way Version 1.0 is written means that it can sometimes be difficult to tell whether various checkpoints are satisfied. The plan, it seems, is to retain some concept of priority or conformance levels, with criteria included which will make it easier for web developers to know that they have met them.

This change of style should help: another recent study, by web-testing specialist SciVisum, found that 40 per cent of a sample of more than 100 UK sites claiming to be accessible do not meet the WAI checkpoints for which they claim compliance. Brewer said this is not unusual: "We noticed that over-claiming a site's accessibility by as much as a-level-and-a-half is not uncommon." So Version 2.0 should be more precisely testable.

The reason for the W3C statement on the DRC findings was, said Brewer, to minimise the risk that the public might interpret the findings as implying that they cannot rely on the guidelines.

City University's Professor Petrie told OUT-LAW: "Our report strongly recommends using the WCAG guidelines supplemented by user testing – which is a recommendation made by W3C." She added that the University's data is "completely at W3C's disposal" for its continuing work on WCAG Version 2.0.

Both the W3C and the DRC are keen to point out that developers should follow the guidelines for site design – WCAG Version 1.0 – but they should not follow these in isolation: user testing, they both agree, is very, very important. (Out-Law, 2004)

Out-law's commentary is interesting because it takes a critical position with respect to the report and its relationship and comments on the W3C WCAG Version 1 and 2. These comments will be considered in more detail in following chapters.

The DRC Report foreword by the Commission's Chairman Bert Massey, states:

This report demonstrates that most websites are inaccessible to many disabled people and fail to satisfy even the most basic standards for accessibility recommended by the World Wide Web Consortium. It is also clear that compliance with the technical guidelines and the use of automated tests are only the first steps towards accessibility: there can be no substitute for involving disabled people themselves in design and testing, and for ensuring that disabled users have the best advice and information available about how to use assistive technology, as well as the access features provided by Web browsers and computer operating systems. (DRC, 2004b, p. v)

The report authors tend to use the term 'inclusive design' rather than universal design.

They comment that:

Despite the obligations created by the DDA, domestic research suggests that compliance, let alone the achievement of best practice on accessibility, has been rare. The Royal National Institute of the Blind (RNIB) published a report in August 2000 on 17 websites, in which it concluded that the performance of high street stores and banks was “extremely disappointing”. 6 A separate report in September 2002 from the University of Bath described the level of compliance by United Kingdom universities with website industry guidance as “disappointing; 7 and in November 2002, a report into 20 key “flagship” government websites found that 75% were “in need of immediate attention in one area or another”. 8 Recent audits of the UK’s most popular airline and newspaper websites conducted by AbilityNet reported that none reached Priority 1 level conformance and only one had responded positively to a request to make a public commitment to accessibility 9. (see DRC, 2004b p. 4)

- RNIB, Get the Message Online (2000)

- B. Kelly, Web Watch: An Accessibility Analysis of UK University Entry Points (2002)

- Interactive Bureau, A Report into Key Government Websites (2002)

- www.abilitynet.co.uk/content/news.htm

and further confirmed the lack of success in achieving accessibility of Web sites by the introduction of the guidelines and the local legislation. This time they were reporting on the state in the UK:

It is the purpose of this report to describe the process and results of that investigation, and to do so with particular regard to the relationship between formal accessibility guidance (such as that produced by the WAI) and the actual accessibility and usability of a site as experienced by disabled users. From that analysis, the report draws practical conclusions for the future development of website accessibility and usability, and makes recommendations directed at the Government, at disabled people and their organisations, at designers and providers of assistive technology, at the developers of automated accessibility checking tools, at designers of operating systems and browsers, at website developers, and at website commissioners and owners. In this way, it is the intention of this report to help realise the potential of the Web to play a leading part in the future full participation of all disabled people in society as equal citizens. (DRC, 2004b, p. 5)

The overall finding includes the comment that compliance with the WAI guidelines does not ensure accessibility. Finding 2 contains the sub-point 2.2 :

Compliance with the Guidelines published by the Web Accessibility Initiative is a necessary but not sufficient condition for ensuring that sites are practically accessible and usable by disabled people. As many as 45% of the problems experienced by the user group were not a violation of any Checkpoint, and would not have been detected without user testing. (DRC, 2004b, p. 12)

The report goes on to describe many things that could be done by humans including training of web content providers and web users, proactive efforts by people with front-line responsibility such as librarians etc and more....

Finding 5 states:

Nearly half (45%) of the problems encountered by disabled users when attempting to navigate websites cannot be attributed to explicit violations of the Web Accessibility Initiative Checkpoints. Although some of these arise from shortcomings in the assistive technology used, most reflect the limitations of the Checkpoints themselves as a comprehensive interpretation of the intent of the Guidelines. (DRC, 2004b, p. 17)

The level of compliance with the guidelines was amazingly low, even given the common perception that compliance levels are not high:

In addition to the proportion of home pages that potentially passed at each level of Guideline compliance, analyses were also conducted to discover the numbers of Checkpoint violations on home pages. Two measures were investigated. The first was the number of different Checkpoints that were violated on a home page. The second was the instances of violations that occurred on a home page. For example, on a particular home page there may be violations of two Checkpoints: failure to provide ALT text for images (Checkpoint 1.1) and failure to identify row and column headers in tables (Checkpoint 5.1). In this case, the number of Checkpoint violations is two. However, if there are 10 images that lack ALT text and three tables with a total of 22 headers, then the instances of violations is 32. This example illustrates how violations of a small number of Checkpoints can easily produce a large number of instances of violations, a factor borne out by the data. (DRC, 2004b, p. 23)

Analysis of the instances of Checkpoint violations revealed approximately 108 points per page where a disabled user might encounter a barrier to access. These violations range from design features that make further use of the website impossible, to those that only cause minor irritation. It should also be noted that not all the potential barriers will affect every user, as many relate to specific impairment groups, and a particular user may not explore the entire page. Nonetheless, over 100 violations of the Checkpoints per page show the scale of the obstacles impeding disabled people’s use of websites. (DRC, 2004b, p. 24)

The report contains many statistics about the speed with which the users were able to complete tasks in what is generally to be understood as usability testing. It showed, in the end, that usable sites were usable and this, regardless of disability needs.

On page 31, there is some explanation of the results:

The user evaluations revealed 585 accessibility and usability problems. 55% of these problems related to Checkpoints, but 45% were not a violation of any Checkpoint and could therefore have been present on any WAI-conformant site regardless of rating. On the other hand, violations of just eight Checkpoints accounted for as many as 82% of the reported problems that were in fact covered by the Checkpoints, and 45% of the total number of problems (DRC, 2004b, p. 31).

After providing the details, the report continues:

Only three of these eight Checkpoints were Priority 1. The remaining five Checkpoints, representing 63% of problems accounted for by Checkpoint violations (or 34% of all problems), were not classified by the Guidelines as Priority 1, and so could have been encountered on any Priority 1-conformant site.

Further expert inspection of 20 sites within the sample confirmed the limitations of automatic testing tools. 69% of the Checkpoint related problems (38% of all problems) would not have been detected without manual checking of warnings, yet 95% of warning reports checked revealed no actual Checkpoint violation.

Since automatic checks alone do not predict users’ actual performance and experience, and since the great majority of problems that the users had when performing their tasks could not be detected automatically, it is evident that automated tests alone are insufficient to ensure that websites are accessible and usable for disabled people. Clearly, it is essential that designers also perform the manual checks suggested by the tools. However, the evidence shows that, even if this is undertaken diligently, many serious usability problems are likely to go undetected.

This leads to the inescapable conclusion that many of the problems encountered by users are of a nature that designers alone cannot be expected to recognise and remedy. These problems can only be resolved by including disabled users directly in the design and evaluation of websites. (DRC, 2004b, p. 33)

The final statement here is most important. It is the main thesis of the DRC Report that usability testing involving people with disabilities is essential to the accurate testing of content.

An important finding of the report was the extremely low level of accessibility of resources. It is explained:

The low rate of expertise identified, the lack of involvement of disabled people in the design and testing processes, and the relatively low use even of automatic testing tools contribute to an environment which makes the currently poor state of Web accessibility inevitable. (DRC, 2004b, p. 38)

What is significant here is that there is such a low rate of universal or, as Petrie says, inclusive accessibility. While this should not be taken as a sign of failure of those accessibility goals, it does suggest that there is a great need for more to be done, and that it is unlikely to be done by the original content creators. This means that third party support should be enabled, and that is dependent on protocols to enable it.

In a sense, the Report places responsibility on the users:

Disabled people need better advice about the assistive technology available so that they can make informed decisions about what best meets their individual needs, and better training in how to use the most suitable technology so they can get the best out of it. (DRC, 2004b, p. 39)

While this is a possible conclusion, it is asserted that the conclusion could equally have been that a better method of ensuring user satisfaction should be developed. There is a general emphasis on responsibility and training in many commentaries on accessibility. Many examples of calls for training of creators, for example, are similar to those within this report but perhaps this responsibility is misplaced. It is interesting to note also that the Report advocates more trust of users to select what they need and want (possibly represented by assistants).

If money is to be spent, the use of better authoring tools may prove cheaper than the training being advocated. And if users need to be served better, perhaps removing the need for them to translate their own needs into assistive technologies is somewhat more attractive.

It is hard to deny the conclusion that:

There is a need to increase the availability of affordable individual expert assessments, but this must be complemented by appropriate signposting to such qualified specialist organisations. That implies a requirement for the education of those who have prime responsibility for assessing the more general assistive technology needs of disabled people (such as occupational therapists, rehabilitation staff, special educational needs coordinators, and Job Centre Plus staff), and of those who are likely to provide advice and training to disabled people (for example, librarians, advisers in information bureaux, as well as professional information and computer technology trainers and assistants). (DRC, 2004b, p. 39)

But the question might be about what is the role these assistants should be trained to contribute. Perhaps training them to complete a simple questionnaire about their needs and preferences would be the easiest and most effective use of training time. Of course, this would only be possible if applications acted on those needs and preferences, and this does mean server improvements. (Note that this issue is considered in some detail in chapter ....)

The report suggests the very practical step of:

The development of on-line user communities and the consequent development by users of their own mutual support arrangements will usefully supplement individual assessments of this sort. (DRC, 2004b, p. 39)

But again this advice is based on a narrow definition of users that was the subject of the report, namely those with disabilities, as made clear in the following extract:

The investigation had three main purposes:

To evaluate systematically the extent to which the current design of websites accessed through the Internet facilitates or hinders use by disabled people in England, Scotland and Wales

To analyse the reasons for any recurrent barriers identified by the evaluation, including a provisional assessment of any technical and commercial considerations that are presently discouraging inclusive design

To recommend further work which will contribute towards enabling disabled people to enjoy full access to, and use of, the Web. (DRC, 2004b, p. 46)

The Report's definition of users is implicitly limited by the scope of the Report. Accessibility, in general, is a far broader issue with a wider scope. There is no way that there could be user groups of the kind suggested by the Report that would cater for all the situations that account for inaccessibility. The various combinations of needs would not be different but identification of classes of needs would be too difficult and the individual differences in needs and preferences would be lost in the process.

Petrie, the author of the DRD report, and others say:

Indeed, accessibility is often defined as conformance to WCAG 1.0 (e.g. [5]). However, the WAI’s definition of accessibility makes it much closer to usability: content is accessible when it may be used by someone with a disability [28] (emphasis added). Therefore the appropriate test for where a Web site is accessible is whether disabled people can use it, not whether it conforms to WCAG or other guidelines. (Kelly et al, 2005, p. 4)

[5] HTML Writers Guild. HTML Writers Guild Web Accessibility Standards. Retrieved March 10, 2005, from Web site: http://www.hwq.org/opcenter/policy/access.htm[28] W3C. Web Accessibility Initiative Glossary. Retrieved March 10, 2005, from Web site:

http://www.w3.org/TR/1999/WAI- WEBCONTENT-19990505/#glossary

They continue:

Thatcher [24] expresses this nicely when he states that accessibility is not “in” a Web site, it is experiential and environmental, it depends on the interaction of the content with the user agent, the assistive technology and the user. (Kelly et al, 2005, p. 4)

[24] Thatcher, J. Prioritizing Web Accessibility Evaluation Data. Proceedings of CSUN 2004:

Kelly et al (2005) argue that the DRD report and other evidence show that there is not yet a good solution to the accessibility problem but that it clearly does not rest in a set of technical authoring guidelines. In fact, they list factors that need to be taken into account in the determination of accessibility:

They argue that priorities must be set for each context and that

This process should create a framework for effective application of the WCAG without fear that conformance with specific checkpoints may be unachievable or inappropriate. (Kelly et al, 2005, p. 7)

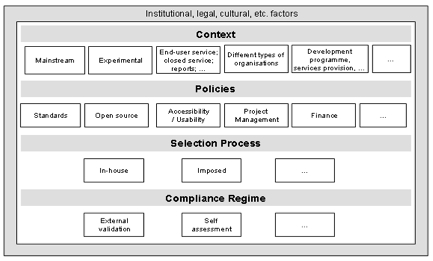

They provide an image of the wider context:

(Kelly

et al, 2005, p. 8)

(Kelly

et al, 2005, p. 8)

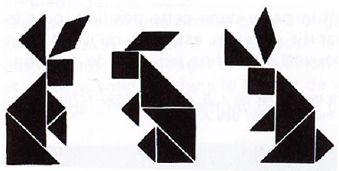

This framework offers one way of thinking about the problems. But a year later many of the same authors offered what they call the 'tangram' approach (see below). It should be noted that the proposed AccessForAll approach provides an operational framework that can include any and all of these contextual issues.

The authors of "Developing A Holistic Approach For E-Learning Accessibility" (Kelly, Phipps & Swift, 2004), point to surveys of accessibility of higher educational sites undertaken in the UK before the DRC Report and comment that the findings are similarly not good,

These findings seem depressing, particularly in light of the publicity given to the SENDA legislation across the community, the activities of support bodies such as TechDis and UKOLN and the level of awareness and support for WAI activities across the UK Higher Education sector. (Kelly, Phipps & Swift, 2004)

But the thrust of their paper is that there is more to accessibility than a technical analysis of conformance with WAI guidelines and that such things as blended learning may provide better solutions in the UK. Blended learning is learning that is not only technology based but includes physical objects and the role of people such as assistants, maybe family members. Jutta Treviranus, on the other hand, in her Keynote address at the 2004 OZeWAI Conference [OZeWAI 2004], emphasised that there is an effort in Canada to use the technology, to exploit the artificiality of it and let it provide for people according to their needs and preferences in ways that humans in the physical world have and often can not (Treviranus & Roberts, 2006). This position does not deny the possibility of human and physical help, but it does make strong demands on the technology for those situations in which it is involved.

There is no reason to follow one approach or the other but rather it is important to be aware of both. Within educational contexts in the UK, the 'SENDA' legislation requires reasonable accommodations to be made to promote inclusive learning. Kelly et al (2005) argue this is done by adopting a holistic approach to accessibility. Where learning is being undertaken in an online environment, the technology should be operating to its highest level of support for accessibility, as required in Canada.

Kelly et al (2005) are raising the expectations in terms of responsibility for teachers, parents, institutions and their performance; the DRC expect the support communities to take a greater role, and Treviranus claims the AccessForAll approach wants more from the technology: while Kelly et al argue for standing back from the online life and including other aspects of life, Treviranus argues that standing back from the original resource and providing what it contains in a form the user can access is what is needed. Kelly et al do this offline and AccessForAll requires the server to do it. In essence, they share the holistic model although they differ in their dependence on computers because they are working in different contexts. Another point of view on their perspectives, and those of the DRC, W3C, and others, asks what burdens are they placing on the humans, and how well can they respond?

Kelly et al (2005) expose their limited scope in the statement:

In our holistic approach to accessible e-learning we feel there is a need to provide accessible learning experiences, and not necessarily an accessible e-learning experience.

but the point they make is valid in a wider context.

By 2006, Kelly and colleagues (Kelly et al, 2006) are moving away from what they describe as their earlier absolute solution to what they refer to as their tangram metaphor with multiple possibilities for satisfaction. They argue that the W3C tests provide a good base for accessibility but do not solve the problems and cannot - there are too many other factors involved.

(

Kelly, 2006)

(

Kelly, 2006)

In a more recent exercise., Kelly and Brown (2007) proposed Accessibility 2.0 and called for greater variety being incorporated into the provision of accessibility.

In referring to the Australian legislative context for discrimination, Michael Bourk says:

In many ways people with disabilities represent different cultural groups. It is important to develop an understanding of different world views in attempting to negotiate policies that accommodate their requirements as citizens and consumers. The discrimination legislation is written from a rights perspective that considers the differences between impairment, disability and handicap. Confusion over the three terms and their application abounds among policy makers and service providers. Impairment refers to a temporary or permanent physical or intellectual condition. Disability is the restrictive effect on personal task performance that the surrounding environment places on people with impairments as a result of unaccommodating design or restricting structures. Handicaps are the negative social implications that occur from disabling environments. Instead of focusing on the limitations of physical or intellectual impairments, a rights model of disability places the emphasis on the disabling effects of an unaccommodating environment that may reduce social status. People may never lose their impairments but their disabilities and handicaps may be reduced with more accommodating environments designed with and for them. (Bourk, 1998)

Additionally, Bourk (1998) makes the point that early on, in the case of Scott and DPI (A) v Telstra (HREOC, 1995),

The Commissioner accepted Telstra’s claim that it had no obligation to provide a new service as stated in s.24 of the Disability Discrimination Act. However, Wilson also accepted the counsel for the complainants argument that they were not seeking a new service but access to the existing service that formed Telstra's USO:

In my opinion, the services provided by the respondent are the provision of access to a telecommunications service. It is unreal for the respondent to say that the services are the provision of products (that is the network, telephone line and T200) it supplies, rather than the purpose for which the products are supplied, that is, communication over the network. The emphasis in the objects of the Telecommunications Act (s.3(a)(ii)) on the telephone service being "reasonably accessible to all people in Australia " must be taken to include people with a profound hearing disability. (HREOC,1995)

In other words, says Bourk, the case establishes it is the service not the objects that must be accessible. He says:

[The Commissioner]'s statement identifies the telephone service primarily as a social phenomenon and not a technological or even a market commodity. Once a social context is used as the defining environment in which the standard telephone service operates, it is difficult to dispute the claim that all does not include people with a disability. In addition part of the service includes the point of access in the same way that a retail shop front door is a point of access for a customer to a shop. Consequently, the disputed service is not a new or changed service but another mode of access to the existing service. It is the reference of access to an existing service that has particular relevance to the IT industry. (Bourk, 1998)

Bourk was writing as a student of Tom Worthington, a recognised Australian expert in accessibility, and an expert witness in the Maguire v SOCOG accessibility case (HREOC, 1999). Bourk makes two points of interest: accessibility is a quality of service and the need for attention is not merely that some people have medical disabilities. Both ideas are fundamental to the work being reported and of particular relevance in Australia.

In fact, the guidance notes for Australian regulations that extend the Australian Disabilities Discrimination Act say:

There is a need for much more effort to encourage the implementation of accessible web design; access to the Worldwide Web for people with disabilities can be readily achieved if good design practices are followed. A complaint of disability discrimination is unlikely to succeed if accessibility has been considered at the design stage and reasonable steps have been taken to provide access. (HREOC, 2002)

While Australian legislation, for example, follows others in using WCAG as the standard specifications for Web content, it is clear that the test of accessibility is not just conformance to the guidelines.

Kelly at al (2005) point out that the W3C Guidelines do not claim to be the arbiters of accessibility but it is clear from most work in the field that they are often used this way. With respect to the W3C position, Kelly et al (2005) argue:

The only way to judge the accessibility of an institution is to assess it holistically and not judge it by a single method of delivery. (Kelly et al, 2005)

The summary of the US National Council on Disability's "Over the Horizon: Potential Impact of Emerging Trends in Information and Communication Technology on Disability Policy and Practice" concludes with the comment that:

"Pull" regulations (i.e., regulations that create markets and reward accessibility) generally work better than "push" regulations (i.e., regulations requiring conformance with regulatory standards), but both have a place in the development of public policies that bring about access and full inclusion for people with disabilities. Neither type of regulation works if it is not enforced. Enforcement provides a level playing field and a reward, rather than a lost opportunity, for those companies that work to make their products accessible. For enforcement to work, there must be accessibility standards that are testable and products that are tested against them. (NCD, 2006)

The AccessForAll framework developed for descriptions of accessibility needs and preferences and of resource characteristics enables the development of tests (of descriptions of resources) that are far more objective and testable than the WCAG criteria that have been shown to be both frequently misjudged and abused when negative results are likely to have adverse ramifications, and that are not able to guarantee what they aim to achieve even if they are correctly evaluated. The AccessForAll framework does no more than identify the objective characteristics of resources.

Given the widespread faith in universal design, any resource that is repaired is likely to be done so 'retrospectively'. This is not a well-structured technical term but rather one that has simply become part of the vernacular of those working in accessibility.

In "Evaluation and Enhancement of Web Content Accessibility for Persons with Disabilities", Xiaoming Zeng (2004) considered a number of surveys of accessibility of Web sites, showing that in those studies, the same sort of results were obtained as in the DRC example. He pointed out that in the case of the study by Flowers, Bray and Algozzine (1999), "Their findings indicated that 73% of the universities’ special education homepages had accessibility errors, yet, with minimal revisions, 83% of those errors [were] correctable" (Xiaoming, 2004, p25).

Overwhelmingly, in most of the cases cited by Zeng, the problems were associated with failure to give a text label to images or giving one that was not appropriate. He points, however, to an exception:

Romano’s study [31] showed that the top 250 websites of Fortune listed companies are virtually inaccessible to many persons with disabilities. Of the 250 sites investigated, 181 of them had at least one major problem (priority 1) that would essentially keep the disabled from being able to use the site. While the study’s findings make it clear that even the best companies are not following WCAG guidelines, most of the problems blocking access to the websites could be easily identified and corrected with better evaluation methods (Xiaoming, 2004, p27).

The difference between a site that contains images that lack proper description and sites that cannot be used at all is, of course, huge. Zeng's contention is that good reporting on evaluations would make it easy for the site owners to correct the defects (Xiaoming, 2004, p36).

He goes on to work on numerical representations of accessibility, and develops his own, and later argues that with suitable software, often the major flaws in the pages can be corrected 'on the fly' to make the sites accessible in the broad sense, even if the images may lack a description. Zeng's contribution is to provide a way of moving from the accessible/inaccessible dichotomy which, as he argues, can cause a huge site to fail the test of accessibility when only one tag is missing while a smaller site can pass and be quite unusable. He limits the scope of his numerical evaluation to those features of accessibility that can be reliably tested automatically (Xiaoming, 2004, p38).

Zeng argues for a numerical value for accessibility mainly for the convenience and machine properties it would have but he states:

A quantitative numerical score would allow assessment of change in web accessibility over time as well as comparison between websites or between groups of websites. Instead of an absolute measure of accessibility that categorizes websites only as accessible or inaccessible, an assessment using the metric would be able to answer the fundamental scientific question: more or less accessible, compared to what? (Xiaoming, 2004, p38)

He cites a number of other benefits such a number might have but he fails to convince the reader that a number would provide useful information for making a site more accessible, although if one is to judge a site, perhaps his system would give a fairer evaluation of a site than the existing and generally used checklist provided by WCAG, which is what people usually refer to for the dichotomous evaluation. He calls his metric the 'Web Accessibility Barrier' score (Xiaoming, 2004, p45).

This approach is in line with that taken by the EuroAccessibility group leading to a smaller group's work for a quality mark. Again, the quality mark, however constructed, approach does not seem to contribute to accessibility for the user, or acccess to resources that would be accessible to the user if not to everyone. It might act as a motivation for content developers to be more careful about the accessibility of their resource, but it is also a source of revenue for those few organisations certified to evaluate sites (in some cases those who proposed the certification scheme) and so there has been deep suspicion about it.

In April 2004, the EuroAccessibility Workshop was held in Copenhagen and came up with an annotated draft of the original WCAG that attempted to make WCAG testable (EuroAccessibility, 2004).

Earlier, in Paris in 2003, the following press release was issued by the EuroAccessibility group:

Twenty three (23) European organisations from twelve (12) countries working in the field of Web Accessibility, together with the W3C/WAI (Web Accessibility Initiative), on Monday, April 28, 2003 have signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for the creation of the EuroAccessibility Project. The MoU sets out governing principles for their co-operation towards the goal of establishing a harmonised set of support services over Europe, which would include a common evaluation methodology, technical assistance, and a European certification authority for Web accessibility (EuroAccessibility, 2006).

One of the things they did was try to make WCAG testable: the plan from the April 30 2004 meeting was as follows:

Explanation Example Take an original WCAG guideline Guideline 1. Provide equivalent alternatives to auditory and visual content. and the original WCAG checkpoints 1.1 Provide a text equivalent for every non-text element (e.g., via "alt", "longdesc", or in element content). This includes: images, graphical representations of text (including symbols), image map regions, animations (e.g., animated GIFs), applets and programmatic objects, ascii art, frames, scripts, images used as list bullets, spacers, graphical buttons, sounds (played with or without user interaction), stand-alone audio files, audio tracks of video, and video. and provide Clarification Points • A text equivalent (or reference to a text equivalent) must be directly associated with the element being described (via "alt", "longdesc", or from within the content of the element itself). It is not unacceptable for a text equivalent to be provided in any other manner i.e. an image being described from an adjacent paragraph and testable statements Statement 1.1.1: All IMG elements must be given an 'alt' attribute. Text: Related Technique: Statement 1.1.2: The appropriate value for the text alternative given to each IMG element depends on the use of the image.

etc

and provide a list of terms used for a glossary.

There is no evidence the group managed to go much further than to develop the statements before the group was disbanded due to lack of funding. in the current context, it is interesting to note that the group were trying to find ways to insist that within a resource, any necessary alternatives should be identified. This is also considered important in relation to AccessForAll and shares the use of what might be called metadata. In the former case, metadata would be embedded in the resource and in the latter it can be independent of it. The practical difference is that the EuroAccessibility approach would not support third party, distributed or asynchronous annotation as easily as does the AccessForAll approach. Nor would it support the continuous improvement of the resource by the addition of accessible components, which is a major aspect of the AccessForAll approach.

The two approaches differ fundamentally in that the EuroAccessibility approach was intended to make a judgmental statement about the resource whereas the AccessForAll approach strictly avoids that.

In their original press release, the EuroAccessibility group stated that:

- the W3C/WAI guidelines, which address accessibility of Web sites, browsers and media players, and authoring tools, may be promoted and implemented differently in different countries,

- there is no harmonised methodology for their application and for assessing the quality of Web sites,

- several "labels" are emerging over Europe,

- governmental organisations express the need of a guarantee of quality concerning Web accessibility,

- the Council Resolution on "eAccessibility" - improving the access of people with disabilities to the Knowledge Based Society (doc. 5165/03), under section II, paragraph 2, letter a, calls on the member states and invites the Commission "to consider the provision of an "eAccessibility mark" for goods and services which comply with relevant standards for eAccessibility.

Consequently, the signatories want to join their efforts in order to:

- co-ordinate with W3C/WAI to develop testing methodology based on the W3C/WAI Web Content Accessibility Guidelines,

- set up a common certification methodology,

- create an Accessibility Quality Mark based on common rules,

- develop an harmonised set of supporting services over Europe, based on a network, set up regional consulting desks,

- disseminate good practices,

- establish a certification authority for Web Accessibility (EuroAccessibility, 2004).

There was a division of labour among the various members of the EuroAccessibility group and a small group received funding to pursue their ideas as the CEN/ISSS WS/WAC developing a "CWA on Specifications for a Complete European Web Accessibility Certification Scheme and a Quality Mark" (CEN/ISSS WS/WAC, 2006).

There was, at the time, significant concern with respect to the EuroAccessibility work after the group had split. It seemed to the author, and others, that the motivation for the work was not simply improving the accessibility of the Web, but also the creation of an industry, in citrcumstances when there was doubt about the value of such an industry and fear it might actually stifle better work. Such concerns were notified formally to the CEN process and discussed informally in many contexts (see corres about this with Makx etc ... early Jan 2006...).

I have been working on what might be useful in DC metadata (see http://dublincore.org/groups/access/). DC metadata is arguably the most common, international metadata anywhere. In the DCMES, we have an architecture and practices that ensure that DC metadata will be transportable, interoperable, easily developed, langauge independent and internationally deployed. It is also easily and consistently expanded to include locally specific information.

DC metadata is formally expanded, i.e. the number of elements and the qualifications for them, when it is clear that this is going to work well for a large community and not break or damage any existing systems or metadata schemas. The DCMI Usage Board works hard on this and has worked to provide suitable specifications for implementations of DC metadata in HTML, XML and RDF - so it is fairly versatile.

Well, what does it make sense for DC metadata users to do about accessibility?

After a lot of work, I have come to think the answer is fairly simple and should work for a lot of people. I think that metadata about accessibility will be used for compliance purposes and for discovery purposes but also for repair purposes.

With existing DC structures:

Using some of the more 'obvious' DC elements such as dc:audience is not advisable, in my opinion. That element, e.g., is about the content or purpose of the resource, not its accessibility and it is not appropriate or useful, in my understanding, to refer to audiences by their accessibility needs or capacities. My explanatons for this are already on the DCMI site at http://dublincore.org/groups/access/.

All of this information is useful and human readable, as well as machine readable, but it falls short of the very precise and rich information that can be conveyed within an EARL statement. The foregoing information is also fairly easily made available by people.

So my proposal is likely to be for one more recommended DC element - dc:access.

For this element, I am thinking that it should do exactly what most of us want, and not pay attention to what disability a user may have, but be an open element about the accessibility of some resource (and BTW, I am including services etc when I say resource). This element would, if I were Queen, be used to draw attention to the user in the Web world, to encourage Web providers to think about their audience and how they are providing for them, to encourage governments and organisations to think about compliance, etc etc. And the value for this element would be a comprehensive EARL statement, pointed to by a URI.

Following this line, I am working on what should be in that EARL statement so that application developers can make the very most of it.

I am also keen to raise the profile of the user and to that end am arguing that there should be more specific DC metadata profiles for people. We change our access needs according to where we are, what we are doing, etc, and for this, we need a set of profiles, I think. We are also affected by what devices we are using to make the access and what it is that we are trying to do - setting the timer on a microwave oven, getting money from an ATM, reading a newspaper. For this we need profiles of contexts, devices, etc. I believe that if we have more specific metadata profiles, we can mix and match them better. See http://ausweb.scu.edu.au/aw03/papers/nevile/index.html for our first pass at this.

At the Dublin Core conference in Seattle in late September, we will be working on these issues. I urge you to send me comments or come if you can (see http://www.ischool.washington.edu/dc2003/).

Liddy

The value of this correspondence at this time is that it establishes the desire, on the part of the author, to shift from a focus on conformance assertions for universal accessibility to qualitative statements about the resource that can be evaluated by the user.

Brown and Gerrard (2006) argue that broadband makes it easier to make accessible content. This is in line with other expectations for the future; as the technology improves, the opportunities should, and one believes do, improve.