check for latest version .......

Interoperability for Individual Learner Centred Accessibility for Web-based Educational Systems

note - this was adapted for the Olmedilla journal with Jutta s co-author...see that version - it is quite good.....

Abstract

For IEEE's Educational Technology & Society Journal see http://www.l3s.de/~olmedilla/events/interoperabilityETSissue.html - author guidelines at http://www.ifets.info/rev.php?pub=true

0. an informative abstract (75 to 200 words) presenting the main points of the paper and the author's conclusions

This paper describes the interoperability underpinning a new strategy for delivering accessible computer-based resources to individual learners based on their specified needs and preferences in the circumstances in which they are operating. The new accessibility strategy, known as AccessForAll, augments the model of universal accessibility of resources to enable systems to focus on individual learners and their particular accessibility needs and preferences. It fits within a new framework for educational accommodation that supports accessibility, mobility, cultural, language and location appropriateness and increases educational flexibility. Its effectiveness will depend upon widespread use that will exploit the ‘network effect' to distribute the responsibility for the availability of accessible resources across the globe. Widespread use will depend upon the interoperability of AccessForAll which, in turn, will depend on the success of the four major aspects of its interoperability: structure, syntax, semantics and systemic adoption.

Keywords

E-learning systems, Interoperability, Accessibility, AccessForAll, Learner profiles, Resource descriptions.

Introduction

This paper describes the effort to give effect to the interoperability goals of a new strategy for delivering accessible computer-based resources to learners based on their immediate specific needs and preferences. There are many reasons why learners have different needs and preferences with respect to their use of a computer, including because they have disabilities. Instead of classifying people by their disabilities, the ‘AccessForAll' approach emphasizes the resulting needs in an information model for formal structured descriptions of those needs and the resources available. It is consistent when describing the needs and preferences of all people, for whatever reason their accessibility is hampered, when they have special requirements. It may be useful to those who are simply trying to gain access to information in a language other than one they comprehend.

AccessForAll uses the same formal, structured information model for describing the needs and preferences of users and the accessibility characteristics of resources. Both sets of descriptions are required so resources can be matched to the needs and preferences of the learner. The aim is to enable systems to share the benefits and burdens of making resources accessible. It needs to be easy to record the necessary information and it needs to be in a form that will make it most useful and interoperable.

There is no doubt that an important aspect of achieving interoperability is the widespread adoption of common solutions to problems. The new framework aims, where possible, to inherit this from extensively used standards. In the case of educational resources and services, there are many major communities concerned with relevant aspects of descriptive standards and of those, a number have been engaged in the development of the AccessForAll model. Cross-domain metadata also has well-established standards that have been considered. The model is based on a set of principles that, when implemented in a variety of standard languages or systems, should maintain their interoperability at syntactic, structural and semantic levels. It also depends upon widespread systemic adoption to generate the volume of accessible components required.

The AccessForAll strategy complements work to determine how to make resources as accessible as possible done primarily by the World Wide Web Consortium Web Accessibility Initiative (W3C/WAI) [1]. The focus of that work is technical specifications for the representation and encoding of content and services, to ensure that they are simultaneously accessible to as many people as possible. W3C also develops protocols and languages that become industry standards to promote interoperability for the creation, publication, acquisition and rendering of resources.

The focus of AccessForAll is ensuring that the composition of resources, when delivered, is accessible from the particular learner's immediate perspective. It complements the W3C work by enabling a situation where a particular suitable resource is discoverable and accessible to an individual learner even when it may not be accessible to all learners. In some cases, this may mean discovery and provision of alternative, supplementary or additional resource components to increase the accessibility of an original resource. The distinguishing feature of AccessForAll is that it assembles distributed, sometimes cumulatively-created, content into accessible resources and so is not wholly dependent upon the universal accessibility of the original resource.

The AccessForAll specifications, while initiated in the educational community, are suitable for any user in any computer-mediated context. These contexts may include e-government, e-commerce, e-health and more. Their use in education will be enhanced if they are adopted across a broad range of domains and used to describe the accessibility of resources available to be used in education even if that was not their initial purpose. The AccessForAll specifications can be used in a number of ways, including: to provide information about how to configure workstations or software applications, to configure the display and control of on-line resources, to search for and retrieve appropriate resources, to help evaluate the suitability of resources for a learner, and in the sharing and aggregation of resources.

The AccessForAll specifications are designed to gain extra value from what is known as the ‘network effect': the more people use the specifications, the more there will be opportunities for interchange of resources or resource components, and the more opportunities there are, the more accessibility there will be for learners.

The first versions of the specifications were created by the Adaptive Technology Resource Centre (ATRC), at the University of Toronto. They were developed further by collaboration between IMS Global Learning Consortium; the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative Accessibility Working Group, and others. They have been considered formally by CEN ISSS MMI-DC, CEN ISSS LTSC and ISO JTC1 SC36 as well as at the national level by Industry Canada, BECTA in the UK, and AGLS (in Australia).

Provision of Networked Accessible Resources

There are a number of approaches to making networked resources accessible, whether on the Internet or on an Intranet.

The first and most common approach is to create a single resource (Web site, Web application) that meets all the accessibility requirements. Such a resource is known as a universally accessible resource. While this approach would work well in many situations, it is not often that authors succeed in making their resources ‘universally accessible', especially when they contain interactive components. As well, it is possible to make a resource that satisfies the guidelines but is, in fact, not accessible to everyone. There are also potential problems due to lack of attention to usability principles that may account for lack of satisfactory access [3]. Indeed, a resource may be accessible to everyone, but optimal for no one. Often, systems concerned about accessibility avoid resource components that may be very effective, entertaining or efficient for some learners for fear they will not be accessible to all learners. Valuable new technologies and techniques are often not used for fear that they may not meet the requirements (Macromedia's Flash is a typical example).

The second approach used by a number of educational content providers is to create two versions of a resource: a media rich version and an “accessible version,” the latter being stripped of all media that may cause accessibility problems. While this solves some of the problems with the first approach, it can also cause other problems. In some cases, the accessible version is not maintained as well as the default version, giving learners with disabilities an out-of-date, different view of the information. More often, students who perhaps need more assistance get less because they are using an impoverished version of the resource. The idea that learners with disabilities are a homogenous group that is well served by a single bland version of a resource is flawed.

The third approach differs from the first two in a number of ways. Accessibility requirements are met not by a single resource but by a resource system. Rather than a single resource or a choice between two resource configurations, there can be as many configurations as there are learners. The ability of the computer mediated environment to transform the presentation, change the method of control, to disaggregate and re-aggregate resources and to supplement resources is capitalized upon to match resource presentation, organization, control and content to the needs of each individual learner. This is the AccessForAll approach [4].

Describing Control and Display Requirements for interoperability

One aspect of interoperability is the ability to share the same kind of information with others using the same systems and acting with the same goals. Another is to work across devices including using different hardware and software without losing the necessary ‘look and feel' that facilitates learner mobility between devices.

W3C has a Working group focused on Device Independence, another focused on the Mobile Web and a third working on Evaluation and Repair. All three Working Groups produce specifications that are important to the interoperability of AccessForAll. These groups do not work specifically on specifications for learners but learners are included in the user groups of concern to them.

The Device Independence Working Group is responsible for a protocol known as Composite Capabilities and Personal Preferences. Its general aim is to enable the quick identification of the needs of a device, such as a mobile phone or a desktop computer, so that user requests will initiate delivery of resource components that are necessary for the correct functioning of the device. A typical example is that when a large display page such as a newspaper page is to be presented on a tiny phone screen, it needs to be accompanied by a transformation that will facilitate navigation through the content without relying on a global view of it. Another important example is given when the mode of transmission of the content has to change to accommodate the device or user. The Working Group, like all other W3C groups, is directed to take into account the accessibility aspects of this, and so Personal Preferences are included. The resulting CC/PP protocol provides an interoperable way of automatically transmitting information to Web servers from devices. This is exactly what AccessForAll wants to do and so it is important that AccessForAll can use the CC/PP protocol.

The W3C Mobile Web Working Group wants to ensure that information about users is available for devices wherever they are but is concerned that such information is not available for abuse by other people or agents. This requirement is one that is shared by the AccessForAll: there is no need for a person to be identified with or by the set of needs and preferences they choose to use (Nevile, 2005).

The W3C Evaluation and Reporting Working Group have developed a language for managing the evaluation of content, typically the validation of it against formal test criteria. It enables the evaluations to be both distributed and cumulative, and at least identified with their evaluator and the time and date of evaluation. AccessForAll descriptions of learners' needs and preferences, and resources' accessibility characteristics, need to be trusted and this information is therefore of interest in their case too.

Describing Content Needs and Preferences and Resources for Exchange

For a network delivery system to match learner needs with the appropriate configuration of a resource, two kinds of descriptions are required: a description of the learner's preferences or needs and a description of the resource's relevant characteristics.

The AccessForAll approach involves specifications for describing learner preferences and needs that define a functional description of how a learner prefers to have information presented, how they wish to control any function in the application and what supplementary or alternative content they wish to have available. It was found that these were the three main classes of such needs that should be in the descriptions.

Specifically:

- display requirements usually include the use of screen readers or enhancers, reading highlights, Braille, tactile displays, visual alerts and structural presentation;

- control requirements usually include the use of keyboard enhancements, onscreen keyboards, alternative keyboards, mouse emulation, alternative pointing, voice recognition and coded input, and

- content requirements usually include the use of alternatives to each of the modes of display (auditory, visual, tactile and what is classed as textual). It includes learner scaffolds, personal style sheets and extra time.

AccessForAll deals with the needs and preferences of learners. It might seem unnecessary to be concerned about preferences at this level, but for some learners with disabilities, they have very limited means to access resources, and it may be essential to them that they have their exact needs satisfied. To distinguish them from learners who have the capability to use other systems but prefer a particular set, it would be inadequate to limit their acquisition of resources just because their first preference was not satisfied. There is also a third situation that needs to be considered; some learners can have problems induced by certain sets of conditions, such as when flashing content causes them to have epileptic fits. For this reason, the three classes of essential, preferred, and prohibited need to be available to qualify the requirements.

In defining requirements, AccessForAll does not mention the reason for any of the requirements. In some cases, learners with disabilities use assistive technologies to emulate other technologies, such as when a head-pointer is used to emulate the standard mouse so that as far as the functioning of the computer and the resource is concerned, there is no special accommodation. When the assistive technology impacts other technologies, as happens when a section of a screen is used for an on-screen keyboard, there are often detailed requirements not only for the display functions but also for the keyboard itself. Some learners need to specify the attributes of their keyboards, such as the size and separation of the keys, and others want to take advantage of features of the keyboard software they are using. Another kind of problem arises when a learner who has previously used a resource on a desktop computer tries to reuse the resource on a telephone screen.

If learners are to be able to quickly configure their devices, they need their needs and preferences to be quickly recognized and implemented by the device they are using. Similiarly, if they are to search for appropriate resources (including where their search for resources causes their system to search for accessible components from which to make the resource they want), their needs and preferences descriptions have to be available to the search engine for searching and matching with the resources and their components. Where this is happening across collections of resources, a common way of describing the resources will be necessary and it will need to mirror the descriptions of the resources. So interoperability between the two sets of descriptions is necessary so that even though one is concerned with the user's needs and the other with a resource, they can both be used by the search engine. In effect, this means that the description of the learner's needs should be in the same format as the description of the resource.

Typically, learners with special needs will be looking for resource components that are developed by specialists. Usually specialists who have not made the original resources produce closed captions, image descriptions and video files of people signing. They are likely to know the standard assistive technologies and what they will require and can do to use the special components. In automating the matching process for the learner, it is very important that the standard triggers are available for the assistive technologies. This means that the resources should be described in the way they can be understood by particular assistive technologies but also so that there is a generic description specification that all the assistive technologies can be expected to refer to. For this reason, care has been taken in AccessForAll to ensure that there is a seamless match and the established industry terms are used. The implications for interoperability here are for exchange between systems known as ‘user agents' that typically include browsers. It is well known that browser developers pride themselves on the non-standard features they offer and that it is not easy to satisfy all browser specifications simultaneously. Fortunately, assistive technology developers who have a much smaller market are often more concerned to serve their customers and their industry associations. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize their differences and allow for their use so the AccessForAll model has to be capable of such flexibility. In fact it aims for some generic functions to be described in a common way while allowing for extensions to accommodate custom functions or features.

As most resources for educational purposes are created within educational institutions, and therefore described by the educational community, descriptions of those resources are usually created according to standards designed for the educational community. Having worked with the goal of sharing resources for some time now, the educational communities have a number of ‘standards', the best-known being those developed by IEEE LOM, known Learning Object Metadata, and now an ISO standard (ISO ????) [ref]. Clearly, the accessibility characteristics of resources that are ‘learning objects' need to be described in a way that interoperates with all other aspects of LOM descriptions.

The IMS Global Learning Project, an consortium of educational organizations, has adopted the LOM and added the Learner Information profile (LIP) that describes the attributes of the learner. AccessForAll was an IMS initiative and so it closely resembles the LIP in order to operate as an extension of the LIP. (In fact, the IMS version is known as the Accessibility for LIP profile (AccLIP) [ref].

Often, however, educational activities involve learners using resources that have been developed and described by other communities for their own purposes. For example, technical manuals are often used in Computer Science courses but they are not usually written for this purpose. Government information is often used in education, as are images of paintings and objects held in museums and galleries. The resources to be used by learners then, do not always originate from the educational or even the same communities and their description for discovery purposes can be very specific to the community from where they come. In order to discover resources across communities, or disciplines then, the descriptions of the accessibility characteristics of resources need to be consistent with descriptions used in those communities.

The Simple Dublin Core Metadata Element Set is an ISO standard (ISO 15836) for core resource description metadata [11]. There is also a Qualified Dublin Core Metadata Element Set with additional terms and extensions. Dublin Core metadata is not domain specific. The Dublin Core Metadata Initiative has worked on cross-disciplinary metadata (DC metadata) for resource description and provides a base set of descriptive elements that support cross-domain discovery. As DC metadata is commonly used by governments, museums, galleries, and others for information sharing, AccessForAll needs to be able to take advantage of their interoperability. DC metadata also has the advantage that it is used in many countries for resources that are created in many different languages and so can be used for cross-language discovery.

DC Metadata and IEEE LOM and IMS LIP metadata are very different. They vary at several levels, including specifically at the structural, and semantic levels. They share the use of standard syntax including HTML [ref], (X)HTML [ref] eXtensible Markup Language (XML) [ref], in particular, and the more narrowly defined Resource Description Framework XML (RDF) [ref]. Both XML and RDF are extensible, so this does not mean very much in terms of functional interoperability.

DC metadata is for describing resources and does not support rich descriptions of people but as people are not described in the learner needs and preferences profile, this was not a problem. It would be necessary, however, for there to be DC usable descriptions of learners' needs and preferences but as described elsewhere [ref], these need not be Dublin Core descriptions although they could be DC-style descriptions described as DC resources to allow for their discovery.

In summary, AccessForAll needs to interoperate with a number of other relevant metadata specifications and standards.

The History of the AccessForAll Interoperability Efforts

Originally, the AccessForAll descriptions were developed for an in-house application. The Inclusive Learning Exchange (TILE) [ref], allowed the system to choose among a set of resource components according to the learner's needs and preferences. The resources were treated at the atomic level, each image and chunk of text, such as text articles, captions for other rich media resources, and so on, being separately stored and described. The learner's needs and preferences information was set within the system and variable at any time the system was being used. The descriptive information was related in a hierarchical decision-tree that allowed for different levels of detail appropriate for the circumstances. The resource components in the learning system were described so that their potential for matching was available to the application that chose and assembled the components to be delivered as the resource. There was no need for interoperability.

The original specifications were adopted by the IMS Global Learning Project with the aim that they would become interoperable by extending the IEEE LOM and the IMS LIP in a consistent way. They were dependent upon their common expression in an XML binding, inherited from TILE, for interoperability.

The IMS Accessibility Special Interest Group [ref] sought permission to work towards an open standard with participation from others (including the DCMI Accessibility Working Group [ref]) in order to increase the opportunities for widespread adoption and interoperability. This collaboration led to the deconstruction of the original AccessForAll model and a new construction, without loss of particulars, as an abstract model (see below). During this process, it was crucial to the success of the outcome that it would not lose its relationship with the LIP or the LOM.

Before the adoption of DCMI of AccessForAll as a recommendation to the DC users community, and in anticipation of a revised, interoperable IMS version of the AccLIP and AccMD [ref], the IMS specifications were forwarded to ISO for adoption as a multi-part international standard. The ISO process involves support and participation for a range of nations and helps foster international adoption of the specifications. As the specifications were contributed by IMS, unlike many of the ISO standards, they will be free to those who want to use them.

Enabling Interoperability

To clarify the nature of DC metadata, the DCMI developed an abstract model of DC metadata which was adopted in early 2005. This model defines the scope and functions of DC metadata that enables its implementation using a range of syntaxes without loss. Where the syntax is standard, as where standard XML or RDF is used, both the structure (defined in the abstract model) and the syntax will be interoperable across DC metadata applications (usually known as application profiles [ref])

In order to be recommended by the DC Usage Board for general adoption by the DC community, AccessForAll metadata needed to be explained in DC terminology. In effect, by late 2005, this meant it had to comply with the DC Abstract Model. As AccessForAll did not have an abstract model, developing one seemed like a good exercise. In the end, it was a very constructive exercise.

Abstract models are not easily developed when what they are to represent is already defined but in the case of AccessForAll, there was the opportunity to redefine it concurrently with developing its abstract model. DCMI introduces its abstract model as follows:

This document specifies an abstract model for DCMI metadata [DCMI]. The primary purpose of this document is to provide a reference model against which particular DC encoding guidelines can be compared. To function well, a reference model needs to be independent of any particular encoding syntax. Such a reference model allows us to gain a better understanding of the kinds of descriptions that we are trying to encode and facilitates the development of better mappings and translations between different syntaxes.

This document is primarily aimed at the developers of software applications that support Dublin Core metadata, people involved in developing new syntax encoding guidelines for Dublin Core metadata and those people developing metadata application profiles based on the Dublin Core. [http://dublincore.org/documents/abstract-model/ accessed 25/9/2005]

DCMI then provides a set of definitions and rules followed by a diagram expressed in a formal graphical representation format known as Unified Modeling Language (UML) [ref]. The AccessForAll abstract model is now similarly described. It inherits a number of definitions and rules from the DC Abstract Model and has as unique definitions and rules:

The abstract model of the preference sets defined in the AccessForAll framework is as follows:

· Each person has zero or more needs and preferences.

· Each needs and preferences has zero or more adaptability statements.

· Each needs and preferences has zero or more contexts.

The abstract model of the resources defined in the AccessForAll framework is as follows:

· Each resource meets the needs and preferences (of a person).

· Each resource has zero or more adaptability statements.

· Each resource may be related to zero or more alternative resources.

· Each adaptability statement may contain access mode information.

[AccessForAll: an Accessibility Framework http://dublincore.org/accessibilitywiki/AccessForAllFramework accessed 24/9/2005

and the diagrammatic representation is:

[from David Weinkauf, AccessForAll: an Accessibility Framework at http://dublincore.org/accessibilitywiki/AccessForAllFramework accessed 24/9/2005]

The AccessForAll abstract model matches the Dublin Core Abstract model. It is described as an AccessForAll Framework and includes, significantly, both the user's needs and preferences profile and the resource profile. In fact, the person could be considered just another resource, but this may be too abstract. Not everything that will be useful to have as AccessForAll metadata is unique to the AccessForAll model so a significant amount of information will be expressed using standard DC elements. Exactly how to do this will be described in what is known as a DC Application Profile [ref] for which specific terminology (semantic values) will be defined. The value of this work for DC users is that they will be able to express the AccessForAll metadata in DC compliant ways so it will interoperate with other DC metadata. They will also be able to use standard DC applications without significant modification.

An encoding of AccessForAll metadata for use in an IEEE LOM Application is under construction by the CEN-ISSS Learning Technologies Workshop [10]. This work has been undertaken in parallel with the development of the AccessForAll abstract model but is, at the time of writing, incomplete.

See also work of Mikhail Nilssen

Between them, IEEE LOM and DC metadata describe a vast proportion of the resources that are of interest in education. Many educational systems use LOM metadata to describe their resources but others use DC metadata. It makes sense that these two communities should be able to exchange metadata records about their resources so they can, in fact, share their resources. To do this, they need to be able to transform metadata from one specification to the other. There is an activity, started in 2001, that aims to bring the two sets of specifications into harmony [ref]. It cannot be done easily because LOM and DC metadata are based on very different models.

The LOM abstract model is hierarchical and instead of having property-value pairs as DC metadata does, it has a rule that every element is either a container (of another element) or a leaf (to another element). This is a more typical model but very different from the DC one. Attempts to cross-walk (transform) metadata from the LOM to DC metadata, or vice-versa, typically result in substantial loss either in detail or value. LOM metadata has many more elements than the simple DC core set and so when LOM metadata is transformed into DC metadata there is a many-to-few transformation with a lot of metadata being discarded. When DC metadata is transformed for use as LOM metadata, a lot of the metadata of interest to educators is found to be missing. DC metadata lacks the structure of LOM metadata: DC metadata is ‘flat' while LOM metadata is hierarchical.

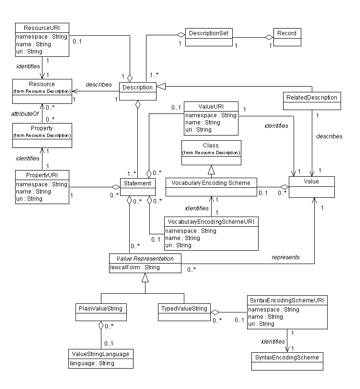

There have been several attempts to find good ways of moving metadata back and forth from one system to the other without loss and in late 2005 there has been what appears to be a useful model developed for this. Early work focused on moving information expressed as metadata from one system to the other but recently it has been decided that it is more effective to relate the elements that contain that information and then express the metadata in whatever syntax is chosen. Mikael Nilsson explains this in his model:

[from Mikael Nilsson, Figure 1 . A possible structure of a future metadata standardization framework.

From “The Future of Learning Object Metadata Interoperability Towards a Framework for Metadata Standards“ publisher etc?]

Nilsson concludes:

We have demonstrated that true metadata interoperability is still, to a large extent, only a vision, and that metadata standards still live in relative isolation from each other. The modularity envisioned in application profiles is severely hampered by the differences in abstract models used by the different standards, and efforts to produce vocabularies often end up in the dead end of a single framework. In order to enable automated processing of metadata, including extensions and application profiles, the metadata will need to conform to a formal metadata semantics.

To achieve this, there is a need for a radical restructuring of metadata standards, modularization of metadata vocabularies, and formalization of abstract frameworks. RDF and the Semantic Web provide an inspiringly fresh approach to metadata modelling: it remains to be seen whether that framework will be reusable for learning object metadata standards.

This suggests that is may not be until there is a shared LOM/DC abstract model for education that there will be perfect interoperability between DC and LOM resource descriptions but it may, on the other hand, be possible in the particular case of AccessForAll metadata because of it is based on a more interoperable abstract model.

metadata

those with other resources describe

This description should be created by learners or by their assistants, usually with a simple preference wizard. It should be of needs and preferences that are essential to a learner's functioning as a consequence of their having a disability or it may be that the circumstances, devices, or other factors have led to the mismatch between them and the resources they wish to use. Each learner may need more than one description of needs and preferences or accessibility profiles to accommodate their changing needs within different contexts. A learner may have one profile for work and another for home if the bandwidth is different, for example. In addition, these profiles should be able to be changed to suit immediate needs and preferences, to accommodate changes in circumstances or context.

Describing Resource Characteristics: The Content

The AccessForAll approach requires finer than usual details with respect to embedded objects and for the replacement of objects within resources where the originals are not suitable on a case-by-case basis. This is made possible by describing the resources in terms of their modes of perception – auditory, visual, tactile, and text.

Resources require a set of simple descriptive statements about their content: how transformable is this resource, what access modality is used (vision, hearing, text literacy or touch) and what is the location of any known equivalent alternative. The problem is that most resources consist of multiple objects combined into what are commonly known as pages. Sometimes this is done once and there is a static version available and sometimes it is done dynamically for the learner. AccessForAll allows for the components that comprise the version of the resource that is sent to the learner to be distributed. That is, they need not all be located in the same place. In addition, the original composite resource may contain objects that can to be transformed or used to replace or augment others and were created in the original authoring process. Equally, they may have been created in response to some other learner's difficulties with the original resource.

The IEEE LOM (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers' Learning Object Metadata Standard [9]) is a profile for learning object metadata. It contains a description of semantics, vocabulary, and extensions.

in "Metadata Principles and Practicalities" [8].

The Benefits of Interoperability

A key challenge in accessibility is the diversity of need; different people require different accommodations. Established approaches towards addressing this are to allow customization by the end learner (e.g. text size and color) and to offer alternative presentations of the same content where automatic customization is not possible (e.g. text description of diagrams or audio descriptions of video content).

Integrated eLearning systems potentially offer an efficient way of managing and even extending this. They can personalize the way the interface and the content are presented to the learner and further, which content is presented to the learner can be determined by the system on the basis of stored information about the individual learner and their preferences.

Such eLearning systems offer the educational institutions the opportunity to efficiently manage their requirement to meet the needs of their disabled students. If they implement student profiles and adopt the AccessForAll approach, the system will “know” how best to present content and interfaces to each individual learner. If they implement the approach for the metadata of the content stored in their repositories, then the system can automatically offer the learning content, and other information, in the most appropriate format to meet individual learner needs. Furthermore, disabled students and their faculty or advisors will be able to instigate automated searches of the content associated with any particular course or module, and determine if any of it presents particular accessibility problems for that student.

With this information, they will be able to commission alternative formats of the same content or locate an alternative learning activity ahead of time if that is more appropriate.

The AccMD specification [13]

Best Practice Guide [14] for more information.

The Web-4-All [16] project is a collaboration between the Adaptive Technology Resource Centre at the University of Toronto and the Web Accessibility Office of Industry Canada to help meet the public Internet access needs of Canadians with disabilities and literacy issues.

The Inclusive Learning Exchange [15] (TILE)

FUTURE WORK AND CONCLUSION

It also needs to be used as an extension of the IMS LIP and in other related specifications including those for e-Portfolios [ref], ….

The AccessforAll specifications show how the AccessForAll strategy can be implemented. They are not prescriptive about the encoding that should be used. Significantly, they are not prescriptive about what constitutes accessibility. There are endless opportunities, given the model and strategy, to take further advantage of new technologies.

The Semantic Web offers one obvious technology that will be enabled by the AccessForAll approach. Already the AccessForAll specifications recommend using EARL so that the metadata will be as flexible and rich as possible. The range of other extensions includes opportunities for valuable cross-lingual exchanges to suit learner needs as well as cross-disciplinary changes of emphasis. Applications and Web services that transform resources or resource components to suit the needs of users with cognitive disabilities is a huge area that has hitherto not received the attention it deserves.

REFERENCES

[1] WAI Content Guidelines for creating accessible Web pages: http://www.w3.og/TR/WAI-WEBCONTENT/

[2] Cooper M., Communications and Information Technology (C&IT) for Disabled Students, in: Powell S. (ed.), Special Teaching in Higher Education- Successful Strategies for Access and Inclusion, (Kogan Page) London 2003

[3] http://www.drc-gb.org/publicationsandreports/report.asp

[4] http://www.imsglobal.org/accessibility/

[5] (see W3C/WAI ER).

[6] http://www.microsoft.com/enable/research/ and http://webstandardsgroup.org/resources/documents/doc_317_brettjacksontransitiontoxhtmlcss.doc

[7] http://www.w3c.org/TR/ATAG10/

[8] Metadata Principles and Practicalities, available at: http://www.dlib.org/dlib/april02/weibel/04weibel.html

[9] IEEE 14.84.12.1 - 2002 Standard for Learning Object Metadata: http://ltsc.ieee.org

[11] Dublin Core Metadata Initiative: http://dublincore.org/

[12] See: http://www.w3.org/TR/EARL10/

[13] IMS AccessForAll Meta-data Information Model Version 1.0 Final Specification, available at: http://www.imsglobal.org/accessibility/accmdv1p0/imsaccmd_infov1p0.html

[14] IMS AccessForAll Meta-data Best Practice and Implementation Guide Version 1.0 Final Specification, available at: http://www.imsglobal.org/accessibility/accmdv1p0/imsaccmd_bestv1p0.html

[15] http://www.inclusivelearning.ca/

[16] http://web4all.ca