Site Navigation

Contents of Thesis ack'ments - Preamble - Introduction -Accessibility - W3C/WAI - LitReview - Metadata - Accessibility Metadata - PNP - DRD - Matching - UI profiles - Interoperability - Framework - Implementation - Conclusion - References - Appendix 1 - Appendix 2 - Appendix 3 - Appendix 4 - Appendix 5 - Appendix 6 - Appendix 7

Work on making computer text 'accessible' had started at least by the early 1990's and the processes being advocated then, are the base for what is used today. The term accessible has already been described. Here, the history of the effort is presented briefly. Then the emergence of the W3C and later, in 1997, the Web Accessibility Initiative is described in so far as the history is relevant. What are now known as the Web Accessibility Initiative's guidelines for accessible content, and published by W3C, started life before either the Web or W3C was significant in the field. They, like so many other things that happen, have historical roots that possibly help explain why they are as they are. The work of those responsible for authoring and recommending the guidelines, the W3C WAI Working Groups, is considered in so much as it is relevant and then the guidelines themselves are introduced.

The significance of the guidelines in this context is not how comprehensive or effective they are, but rather how they are determined and the role they play in stimulating technology development by allowing for the generalisation of specific accessibility problems.

In 1994, in the abstract to "Document processing based on architectural forms with ICADD as an example", the authors wrote:

ICADD (International Committee for Accessible Document Design) is committed to making printed materials accessible to people with print disabilities, eg. people who are blind, partially sighted, or otherwise reading impaired. The initiative for the establishment of ICADD was taken at the World Congress of Technology in 1991. (Harbo et al, 1994)

Earlier in the article they describe the mission of ICADD as:

The ambition of ICADD is that documents should be made available for people with print disabilities at the same time as and at no greater cost than they are made available to people who can access the documents in traditional ways (usually by reading them on pages of paper). This ambition presents a significant technological challenge.

ICADD has identified the SGML standard as an important tool in reaching their ambitious goals, and has designed a DTD that supports production of both "traditional" documents and of documents intended for people with print disabilities (eg. in braille form, or in electronic forms that support speech synthesis).

It should be noted that the proposed way of making the materials available was to use SGML, the predecessor of HTML that was the first and has remained the main markup language for the Web.

After WWW94 in CERN , Dan Connolly (1994) reported his participation and recorded with respect to a discussion session chaired by Dave Raggett:

One interesting development is that right now, HTML is compatible with disabled-access publishing techniques; i.e. blind people can read HTML documents. We must be careful that we don't lose this feature by adding too many visual presentation features to HTML.

It might be noted that this early conference was held before the World Wide Web Consortium was formed. Yuri Rubinski was at that early conference at CERN. He, as an ICADD pioneer, had been involved in making sure that SGML could be used for other than standard text representations and he and his colleagues did not want their work to be lost in the context of the new technology, the fast emerging Web. A year later, at WWW4 in Boston in December 1995, Mike Paciello, another ICADD pioneer, offered a workshop called "Web Accessibility for the Disabled".

Meanwhile, the World Wide Web Consortium [W3C] was being formed with host offices in Boston, Tokyo and Sophie-Antipolis in France. It came into existence in late 1994. Within a short time, the American academies were working on what they were calling at the time the National Information Infrastructure (NII). It was a time of great expectations for the new technologies. In a report published in August 1997, the American National Academies called for work to ensure that the new technologies were accessible to everyone:

It is time to seek new paradigms for how people and computers interact, the committee said. Current computer systems, which arose from models conceived in the 1960s and 1970s, are based on the concept of a single user typing at a computing terminal. These systems have limitations, however. For example, using many applications simultaneously can be awkward, and inefficiency can ensue when multiple users with different abilities and equipment try to access and work on the same documents at the same time. No single solution will meet the needs of everyone, so a major research effort is needed to give users multiple options for sending and receiving information to and from a communication network. The prospects are exciting because of recent advances in several relevant technologies that will allow people to use more technologies more easily.

This is a time when tremendous creativity is required to take advantage of the vast array of new technologies coming forth, such as virtual reality systems and speech recognition, eye-tracking, and touch-sensitive technologies," said steering committee chair Alan Biermann, chair of the Levine Science Research Center at Duke University, Chapel Hill, N.C. "But the point remains that we are still using a mouse to point and click. Although a gloriously successful technology, pointing and clicking is not the last word in interface technology.

The report encourages both government and industry to invest in research on the components needed to develop computing and communication networks that are easy to use. Applying studies of human and organizational behaviors to lay the groundwork for building better systems will be very important to these efforts. New component designs also should take into account the varied needs of users. People with different physical and cognitive capacities are obvious audiences, but others would benefit as well. Communication devices that recognize users' voices would help both the visually impaired as well as people driving cars, for example. It is time to acknowledge that usability can be improved for everyone, not just those with special needs.

And later:

The report draws from a late 1996 workshop that convened experts in computing and communications technology, the social sciences, design, and special-needs populations such as people with disabilities, low incomes or education, minorities, and those who don't speak English (National Academies, 1997).

It should be noted that the steering committee included Gerhard Fischer and Gregg Vanderheiden, both already champions of the need for accessibility of electronic media.

The Committee wrote about research as helping with universal access:

This will complement government policies that address economic and other aspects of universal access. Federal agencies should encourage universal access to the NII by supporting research and requiring adequate development and testing of systems purchased for use at public service facilities (National Academies, 1997).

Very soon after this report was released, in October 1997, a press release was issued by the American National Science Foundation. What follows is from the archived version of it:

The National Science Foundation, with cooperation from the Department of Education's National Institute for Disability and Rehabilitation Research, has made a three-year, $952,856 award to the World Wide Web Consortium's Web Accessibility Initiative to ensure information on the Web is more widely accessible to people with disabilities.

Information technology plays an increasingly important role in nearly every part of our lives through its impact on work, commerce, scientific and engineering research, education, and social interactions. However, information technology designed for the "typical" user may inadvertently create barriers for people with disabilities, effectively excluding them from education, employment and civic participation. Approximately 500 to 750 million people worldwide have disabilities, said Gary Strong, NSF program director for interactive systems.

The World Wide Web, fast becoming the "de facto" repository of preference for on-line information, currently presents many barriers for people with disabilities.

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), created in 1994 to develop common protocols that enhance the interoperability and promote the evolution of the World Wide Web, is working to ensure that this evolution removes -- rather than reinforces -- accessibility barriers.

National Science Foundation and Department of Education grants will help create an international program office which will coordinate five activities for Web accessibility: data formats and protocols; guidelines for browsers, authoring tools and content creators; rating and certification; research and advanced development; and educational outreach. The office is also funded by the TIDE Programme under the European Commission, by industry sponsorships and endorsed by disability organizations in a number of countries.

I commend the National Science Foundation, the Department of Education and the W3C for continuing their efforts to make the World Wide Web accessible to people with disabilities," said President Clinton. "The Web has the potential to be one of technology's greatest creators of opportunity -- bringing the resources of the world directly to all people. But this can only be done if the Web is designed in a way that enables everyone to use it. My administration is committed to working with the W3C and its members to make this innovative project a success" (NSF, 2007).

Things had moved very quickly behind the scenes. W3C had worked through its academic staff to gain the NSF's support for the project and politically manoeuvred the launch into the public arena with the support of a newly appointed W3C Director and the President of the US. (At this time, there was an offer to the Australian Prime Minister to share the stage with the US President in launching this initiative but he declined, saying it was not a priority (Nevile-something).)

Mike Paciello describes the history thus:

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) have consolidated previously written accessibility guidelines from a range of organisations (Lazzaro, 1998). Principally this work was initiated by Mike Paciello, George Kerscher and Yuri Rubinsky who cofounded the International Committee for Accessible Document Design (ICADD). ICADD established standards for accessible electronic information (ISO 1208-3 and ICADD-22) the forerunners of the WAI guidelines. Whilst Mike Paciello was the Executive Director of the Yuri Rubinsky Insight Foundation from 1996-1999 he was responsible for developing and launching the Web Accessibility Initiative (Paciello ???).

Sadly, Yuri Rabinsky died in 1995. Gregg Vanderheiden became the Co-Chair of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines Working Group, and Mike Paciello, long expected to have become the director of the W3C initiative, went elsewhere when Judy Brewer was appointed to that position.

In an introduction to Mike Paciello as a keynote speaker, NJEDge.net stated:

Mr. Paciello co-founded the International Committee for Accessible Document Design (ICADD), the organization that was responsible for establishing standards for accessible electronic information (ISO 1208-3, ICADD-22) and served as the predecessor to the W3C's Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) (NJED,???).

Another significant player in this history was Jutta Treviranus. She had been working with Yuri Rabinsky at the University of Toronto and quickly emerged, with her colleague Jan Richards, as an expert who could lead the development of guidelines for the creation of good authoring tools. In a paper entitled "Nimble Document Navigation Using Alternative Access Tools" presented at WWW6 in 1997, she argued that:

Due to the evolution of the computer user interface and the digital document, users of screen readers face three major unmet challenges:

- obtaining an overview and determining the more specific structure of the document,

- orienting and moving to desired sections of the document or interface, and

- obtaining translations of graphically presented information (i.e., animation, video, graphics)

She further stated that:

These challenges can be addressed by modifying the following:

- the access tool (i.e., screen reader, screen magnifier, Braille display),

- the browser,

- the authoring tools, (e.g., HTML, SGML, plug-in, Java, VRML authoring tools),

- the HTML specifications, HTML extensions, Style Sheets,

- the individual documents, and

- the operating system (Treviranus, 1997).

Treviranus was already the Chair of the Authoring Tools Accessibility Working Group for W3C, and has been ever since. Clearly, the principles of the ICADD developments were on their way into the W3C guidelines.

With the appointment of Wendy Chisholm as a staff member at W3C, the work of TRACE, her former employer and the laboratory of Gregg Vanderheiden (co-chair of WCAG Working Group), the Wisconsin-based researchers contributed significantly to W3C's WAI foundation. Judy Brewer, the Director of W3C responsible for WAI, was not herself an expect in content accessibility at the time but strong in disability advocacy.

The W3C guidelines were already crawling by the time they entered the W3C process.

W3C WAI inherited, from ICADD's ISO 1280-3 and later standards, the architecture of documents where a Document Terms Definition document (DTD) was used to describe the structure of the document in a common language, or a language that could be mapped to a common terminology, but the style applied to those structural objects could be set any number of times by a designer. Presentation could, and should, be separated from content, as the slogan goes.

ICADD is aware that it is unrealistic to expect document producers and publishers to use the ICADD DTD directly for production and storage. Instead a "document architecture" has been developed that permits relatively easy conversion of SGML documents in practically any DTD to documents that conform to the ICADD DTD for easy production of accessible versions of the documents. ...

The approach of ICADD is interesting, not least because it illustrates that document portability and exchange in SGML can be achieved by other means than standardizing on a single DTD in the exchange domain. In ICADD, portability is achieved by specifying mappings onto a standardized DTD. (Harbo et al, 1994)

This is an important article for its explanation of how, given an architecture for markup, a single application can be used to read the markup and present the content in different ways according to instructions about how to present each type of content. This was the state of the art in 1994.

The article further explains:

The relatively new international HyTime standard (ISO 10744) introduced the notion of architectural forms. With architectural forms, SGML elements can be classified by means of #FIXED attributes as belonging to some class. In HyTime, architectural forms are used as a basis for processing hypermedia documents, but their use is not limited to that.

With good foresight, the authors note the good and bad features of ICADD and then, in their conclusion, say:

Still, the approach chosen by ICADD does seem to be a good one, despite its lack of full generality. The problem that ICADD faces is not only technical, it is also political and organisational. Improving access through the use of the ICADD intermediate format will only happen if information owners and publishers choose to support it; ICADD depends on the DTD developers to specify the mapping onto the ICADD tag set. By using architectural forms for the specification, ICADD reduces the perceived complexity of specification development; and the same time this development - by having the specification be physically part of the DTD - it is stipulated to be an integrated part of the DTD development itself, thus presumably increasing the chances of support from the DTD developers.

What they said of ICADD seems to have accurately predicted what would happen to Web content markup in the next decade. What is now obvious, is that the influence of the early solutions and players was going to prove dominant and the SGML solutions would be, in some ways, taken for granted, and even possibly act as a constraint in the future.

It was but a short step to take the ICADD architecture into the Web world, as happened with the introduction of styles, machine-readable specifications for the presentation of structural elements in a Web page. Hypertext MarkUp Language (HTML) was the same kind of language as SGML, although far simpler and, like SGML, referred to a DTD. What had happened in the process of going from the early use of computers to the Web was the introduction of the extensive use of multimedia, particularly graphics, and so HTML needed to be adjusted with element attributes that would stem the flow from inaccessibility back towards some kind of accessibility. The challenge became not one of maintaining the monomedia qualities, which had the qualities Connelly noted, but finding ways to support the proliferation of media without compromising the accessibility.

A simple example is provided by the tag that shows where the inclusion of an image is required. The <img> tag needed an attribute that would provide those who could not see the image with some idea of what it contained. Adding the alt attribute achieved this. Later, adding a new document element to be known as the <long desc> went further to provide for a full explanation of the image.

The idea was that the HTML DTD would specify the structural elements that should be used and the content would be interpreted, according to the provided styles, by the user agent, or 'browser' as it came to be known. What went wrong was that the browser developers were able to exploit this new technology to their advantage by offering browsers that could do more than any other: competition among the browser developers led to constant fragmentation of the standard as they offered both new elements and new ways of using them. The browser battles continue although a decade later, for a variety of reasons, some browsers are appearing that adhere to the current standards.

But determining what the code should do at that level was not the only work of W3C WAI. The jointly-funded activity was to:

create an international program office which will coordinate five activities for Web accessibility:

- data formats and protocols;

- guidelines for browsers, authoring tools and content creators;

- rating and certification;

- research and advanced development; and

- educational outreach (NSF, 1997)

As the Web gained popularity, it acquired more and more users for whom it was inaccessible. As Tim Berners-Lee pointed out in an early presentation of the Web (Connolly, 1994), it had gone from being the communication medium for a lot of geeks who were content with text to a mass-medium and in the process lost some of its most endearing qualities, including the equity of participation that characterised the early Web.

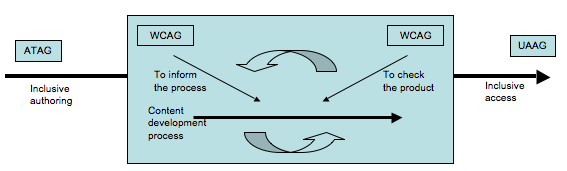

WAI was positioned, then, to receive supplications from all sorts of users who were finding the Web inaccessible or people acting on their behalf. As an open activity, anyone could (and can) join the WAI Interest Group mailing list and voice their opinion. This has been happening for more than ten years and the list of problems is very long. In that time, many obvious problems were determined early and the more difficult ones, such as the identifiable problems for people with dyslexia and dysnumeria, have emerged more recently. Many have been repeated. They are generally classified into three types: problems to do with content, user agents and authoring tools and are channeled towards the three working groups responsible for those areas.

The Working Groups are more focused than the Interest Group and now have charters describing their goals, processes and achievement points that help them prepare a recommendation for the Director of the W3C. Essentially what they do is gather requirements and describe those requirements in generic terminology, aiming to make their recommendations vendor and technology independent and future proof.

The Working Groups consist of experts who do what experts do, generalise and specialise (Mason ???). One might say, then, that the WAI Working Groups are chartered to determine the relevant specialisations for consideration and to generalise from them to define guidelines for accessibility.

The guidelines serve a number of purposes but a clear and specific use of them is to ensure that all W3C recommended "data formats and protocols" contribute to accessibility. The guidelines have themselves assumed the role of data formats and protocols. They have been promoted to content creators in their raw form and this has required considerable support effort which may have been avoided if they had been subsumed into the formal data formats and protocols and those had been the focus of promotion. This is what happened with HTML. The last version of HTML was amended to include the identified accessibility features which now appear as attributes within HTML Version 4.1. EXtensible MarkUp Language (XML) soon replaced HTML as a recommendation from the Director of W3C and with the introduction of XML, more accessibility features were introduced. Despite the W3C Director's recommendation that people should not continue to use HTML, it is still used extensively.

(It is the author's opinion that in many institutions, the money that might have been spent to pressure for better and cheaper authoring tools and to promote the replacement of old tools, instead of increasing the training of creators to use the now deprecated HTML in accessible ways. This is a tractable although difficult problem. Teaching content developers to use XML is frightening to most and so it is not even tried even though in fact it can be done almost without noticing if the right tools are used. The Authoring Tools Accessibility Guidelines, that have not been taken as seriously as the content guidelines, are designed to help make authoring tools that both are usable by people with disabilities and that produce content that is usable by people with disabilities. The point that is so often missed is that if authors use these tools, instead of the many non-conforming tools, without needing to know very much they can produce very accessible content 'unconsciously'. The author believes this would make a much bigger difference than has been the case with the approach of trying to make all content developers accessibility-skilled using bad tools and raw markup. The result is that HTML continues to be used in its raw form and little has been achieved in the way of increased accessibility of the Web. This, despite the reality that the move from HTML to XML requires very little effort beyond using what was HTML 4.1 correctly and ensuring that the right DTD is referred to and the tags are in lower case!)

W3C is a technical standards organisation and their work is devoted to technical specifications. Whereas another type of organisation concerned about accessibility might have worked on developer practices, and what practices should be encouraged within the industry and developer community, possibly with the pressure of ISO 9001 type certification available, W3C has stuck to specifying technical output and been remarkably successful in this process. The result is that many countries, in adopting legal support for accessibility, have also relied on the WCAG specifications, sadly almost always without reference to the authoring tools or user agent specifications.

Conformance with general guidelines is not easily verified. and so the WCAG generalities have been reduced to specifics in each particular case in order to be tested. The Working Groups who are responsible for the generalisations have supported this process by producing specific examples (ref is WAI Techniques) in order to clarify what they mean by their generalisations but, of course, these do not fit every situation and so often are not relevant or helpful. Similarly, as the evaluation of accessibility is difficult, WAI working groups have also produced specific examples of success criteria. In general, the problem is that all these things are subject to interpretation by people with more or less expertise and personal bias. The working groups endeavour to write their recommendations in unambiguous language but, of course, this is not really possible. The result is that conformance is not an absolute quality.

Conformance with formats and protocols is simpler. This is a machine determinable state but it depends upon the formats and protocols having correctly captured the requirements for its effectiveness. As the range of problems that users may have is infinite, it cannot be expected that the guidelines and associated re-defined formats and protocols will cover every possibility for inaccessibility.

what about adding in here the work of SWG-A or should it be pointed to here and appear somewhere else?

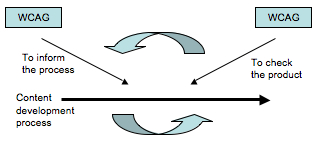

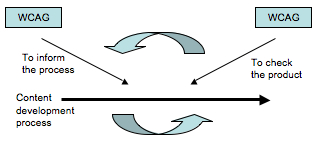

At the time of writing, the authoritative version of the WCAG is "Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 1.0, W3C Recommendation 5-May-1999" [WCAG]. There is a new version under development and the idea of universal design is maintained. The role of WCAG is still to support the developers as they choose what markup to use (of course, many of them are oblivious of the choices and their implications) and then to check that all is well.