Chapter 5: Other

routes to Accessibility

Introduction

This chapter considers a shift in responsibility

for accessibility from the original resource author to a wider

community. Previous work has saddled the resource

developer with the burden of producing a single resource (with

multiple components if necessary) that is accessible to all.

This is the aim of universal design as promoted by the W3C

Web Accessibility Initiative, according to the

WCAG specifications [WCAG-1]. This chapter argues that

the responsibility needs to be distributed among many, including

the creator, the server, the user, etc... It adopts the concept

of on-going inclusive practices and shows that there is a significant

shift in current thinking to support this. It provides evidence

of projects that support this view.

The distribution of responsibility for accessibility lies at the heart of the research. It is precisely because of the need to distribute that responsibility that the need for resource management arises. The benefits of sharing the responsibility are demonstrated by the availability of useful services and other resources for this purpose.

Beyond 'universal' accessibility

It is a major contention of this thesis that not only is

universal accessibility impossible, it is not practical. That

is, the notion that every resource will be made available in

all possible forms so that all users can access the content

equally, is just not sensible. In addition, it is argued that

inclusive design should be promoted in preference to designs

that treat people with permanent disabilities as a

class apart.

With respect to the e-learning context, Van

Assche et al (2006) claimed "that some of the national legislation

(e.g. Section 508 in the

US) might block the development of more appropriate standards

for accessibility of

learning technologies". It is also, according to the community

of experts, a danger of

premature standardisation. Section 508 [s 508] is federal

law in the United States that is based loosely on the universal

design principles. They continued;

We should also develop guidelines

how to provide

alternative representations of learning resources and exploit

the interactive

capabilities of e-learning tools to ensure accessibility.

Web services could

enhance the accessibility capabilities of a number of technologies....

To ensure accessibility interoperability among different

learning technologies, accessibility information should be

embedded in all learning technologies. (Van

Assche et al, 2006, p. 17)

Accessible code and accessible services

Kelly, Phipps and Swift (2004),

pointed to surveys of accessibility of higher educational sites

undertaken in the UK before the DRC Report (2004). They said,

"These findings seem depressing, particularly in light of the

publicity given to the SENDA legislation across the community,

the activities of support bodies such as TechDis and UKOLN

and the level of awareness and support for WAI activities across

the UK Higher Education sector." Unfortunately, these dismal

findings have been replicated in Australia (Nevile,

2004; Alexander

& Rippon, 2007).

But the thrust of the Kelly, Phipps and Swift's paper was

that there is more to accessibility than a technical

analysis of conformance with WAI guidelines. For example, in

the educational context, 'blended learning' may provide better

solutions. Blended learning is learning that is not only technology

based but includes physical objects and the role of people

such as assistants, possibly family members. Jutta Treviranus,

on the other hand, in her keynote address at the 2004 OZeWAI

Conference [OZeWAI

2004], emphasised

that there is an effort in Canada to use the technology, to

exploit the artificiality of it and let it provide for people

according to their needs and preferences. She argues

that humans in the physical world often can not achieve what

computers can do (Treviranus & Roberts,

2006). This position does not deny the possibility of human

and physical help, but it does make strong demands on the technology

for those situations in which it is involved.

There is no reason to follow one approach

or the other but rather it is important to be aware of both.

Within educational contexts in the UK, the 'SENDA' legislation

[SENDA] requires reasonable accommodations to be made to promote inclusive

learning. Kelly et al (2005)

argue this is done by adopting a holistic approach to accessibility.

Where learning is being undertaken in an online environment,

the technology should be operating to its highest level of

support for accessibility, as required in Canada.

So Kelly et al (2005)

raise expectations in terms of responsibility for

teachers, parents, institutions and their performance; the

Disabilities Rights Commission expect the support communities

to take a greater role (DRC, 2004),

and Treviranus claims the AccessForAll approach wants more

from the technology. Kelly et al argue for standing back

from the online life and including other aspects of life. Treviranus

argues that standing back from the original resource and providing

what it contains in a form the user can access is what is needed.

Kelly et al do this offline, and AccessForAll requires the server

to do it. In essence, they share the holistic model although

they differ in their dependence on computers because they are

working in different contexts. Another point of view on their

perspectives, and those of the DRC, W3C, and others, asks what

burdens are they placing on the humans, and how well can they

respond?

These views, demanding effort beyond dependence on a set of

technical specifications for encoding of resources, are shared

by the author and have been the subject of many discussions

involving both Kelly, Treviranus, and other colleagues.

Kelly et al (2005) expose

their limited scope in the statement:

In our holistic approach to accessible e-learning

we feel there is a need to provide accessible learning experiences,

and not necessarily an accessible e-learning experience.

but the point they make is valid beyond the educational context.

By 2006, Kelly and colleagues (2006) were moving away from what they

described as their earlier, absolute solution to what they refer

to as their tangram metaphor (Figure 27), with multiple possibilities

for satisfaction. They share the view of the current research in saying that

the W3C tests provide a good base for accessibility

but do not solve the problems and cannot - there are too

many other factors involved.

In a follow-up, Kelly and Brown (2007)

proposed Accessibility 2.0 and called for greater variety being

incorporated into the provision of accessibility. Kelly and

Nevile have since written a paper suggesting it is even timely

to be working on Accessibility 3.0 (forthcoming???). The point

of these suggestions is that there is a wide range of solutions

that can be brought to bear on the problem, and it is hoped

that together they will accomplish more than the single-focus

approach has managed.

Responsibility for accessibility

In referring to the Australian legislative context for discrimination,

Michael Bourk says:

In many ways people with disabilities represent different

cultural groups. It is important to develop an understanding

of different world views in attempting to negotiate policies

that accommodate their requirements as citizens and consumers.

The discrimination legislation is written from a rights perspective

that considers the differences between impairment, disability

and handicap. Confusion over the three terms and their application

abounds among policy makers and service providers. Impairment

refers to a temporary or permanent physical or intellectual

condition. Disability is the restrictive effect on personal

task performance that the surrounding environment places

on people with impairments as a result of unaccommodating

design or restricting structures. Handicaps are the negative

social implications that occur from disabling environments.

Instead of focusing on the limitations of physical or intellectual

impairments, a rights model of disability places the emphasis

on the disabling effects of an unaccommodating environment

that may reduce social status. People may never lose their

impairments but their disabilities and handicaps may be reduced

with more accommodating environments designed with and for

them. (Bourk,

1998)

Additionally, Bourk (1998)

makes the point that early on, in the case of Scott and DPI

(A) v Telstra (HREOC,

1995),

The Commissioner accepted Telstra’s claim that it

had no obligation to provide a new service as stated in s.24

of the Disability Discrimination Act. However, Wilson also

accepted the counsel for the complainants [sic] argument

that they were not seeking a new service but access to the

existing service that formed Telstra's USO:

In my opinion, the services provided by the respondent

are the provision of access to a telecommunications service.

It is unreal for the respondent to say that the services

are the provision of products (that is the network, telephone

line and T200) it supplies, rather than the purpose for

which the products are supplied, that is, communication

over the network. The emphasis in the objects of the Telecommunications

Act (s.3(a)(ii)) on the telephone service being "reasonably

accessible to all people in Australia " must be taken

to include people with a profound hearing disability. (HREOC,1995)

In other words, says Bourk, the case establishes it is the

service not the objects that must be accessible. He says:

[The Commissioner]'s statement identifies the telephone

service primarily as a social phenomenon and not a technological

or even a market commodity. Once a social context is used

as the defining environment in which the standard telephone

service operates, it is difficult to dispute the claim that

all does not include people with a disability. In addition

part of the service includes the point of access in the same

way that a retail shop front door is a point of access for

a customer to a shop. Consequently, the disputed service

is not a new or changed service but another mode of access

to the existing service. It is the reference of access to

an existing service that has particular relevance to the

IT industry. (Bourk,

1998)

Bourk was writing as a student of Tom Worthington,

an Australian expert in accessibility and an

expert witness in the Maguire v SOCOG accessibility case (HREOC,

1999). Bourk makes two points of interest: first, accessibility

is a quality of service and, secondly, the need for attention

is not merely that some people have medical disabilities. Both

ideas are treated as fundamental by the current research and

of particular relevance in Australia. While Australian legislation,

for example, follows others in using WCAG as the standard specifications

for Web content encoding (HREOC,

2002), it is clear that the best test of accessibility

is not just conformance to the guidelines.

Kelly et al argue:

The only

way to judge the accessibility of an institution is to

assess it holistically and not judge it by a single method

of delivery. (2005)

The summary of the US National Council on Disability's "Over

the Horizon: Potential Impact of Emerging Trends in Information

and Communication Technology on Disability Policy and Practice"

concludes with the comment that:

"Pull" regulations (i.e., regulations that create

markets and reward accessibility) generally work better than "push" regulations

(i.e., regulations requiring conformance with regulatory

standards), but both have a place in the development of public

policies that bring about access and full inclusion for people

with disabilities. Neither type of regulation works if it

is not enforced. Enforcement provides a level playing field

and a reward, rather than a lost opportunity, for those companies

that work to make their products accessible. For enforcement

to work, there must be accessibility standards that are testable

and products that are tested against them. (NCD,

2006)

The AccessForAll framework developed for descriptions of accessibility

needs and preferences and of resource characteristics enables

the development of tests (of descriptions of resources) that

are far more objective and testable than the WCAG criteria.

The latter have been shown to be both frequently misjudged

and abused when negative results are likely to have adverse

ramifications. In addition, the WCAG criteria are

not able to guarantee what they aim to achieve even if they

are correctly evaluated. The AccessForAll framework is an enabler that, itself, does no

more than identify the objective characteristics of resources.

Correctable accessibility errors

Given the widespread faith in universal design and low levels

of achievement, any resource that is repaired is likely to

be done so 'retrospectively'. This is not a well-structured

technical term but rather one that has simply become part of

the vernacular of those working in accessibility.

In "Evaluation

and Enhancement of Web Content Accessibility for Persons with

Disabilities",

Xiaoming Zeng (2004)

considered a number of surveys of accessibility of Web sites,

showing that in those studies, the same sort of results were

obtained as in the DRC example. He pointed out that in the case

of the study by Flowers, Bray and

Algozzine (1999), "Their

findings indicated that 73% of the universities’ special education

homepages had accessibility errors, yet, with minimal revisions,

83% of those errors [were] correctable". (Xiaoming,

2004, p. 25)

Overwhelmingly, in most of the cases cited by Xiaoming, the problems were associated with failure to give a text label to images or giving one that was not appropriate. He points, however, to an exception:

Romano’s study [2002] showed that the top 250 websites

of Fortune listed companies are virtually inaccessible to many

persons with disabilities. Of the 250 sites investigated, 181

of them had at least one major problem (priority 1) that would

essentially keep the disabled from being able to use the site.

While the study’s findings make it clear that even the best

companies are not following WCAG guidelines, most of the problems

blocking access to the websites could be easily identified

and corrected with better evaluation methods. (Xiaoming,

2004, p. 27)

The difference between a site that contains images that lack

proper description and sites that cannot be used at all is,

of course, huge. Xiaoming does not tell us what effect the incorrect

encoding had or how to relate the actual users' needs and

preferences to the faults in the resources. Xiaoming's contention

is that good reporting on evaluations would make it easy for

the site owners to correct the defects. (Xiaoming,

2004, p. 36)

He goes on to work on numerical representations of accessibility,

and develops his own, and later argues that with suitable software,

the major flaws in the pages can often be corrected 'on the

fly' to make the sites accessible in the broad sense, even

if the images may lack a description. Xiaoming's contribution is

to provide a way of moving from the accessible/inaccessible

dichotomy which, as he argues, can cause a huge site to fail

the test of accessibility when only one tag is missing while

a smaller site can pass and be quite unusable. He limits the

scope of his numerical evaluation to those features of accessibility

that can be reliably tested automatically. (Xiaoming,

2004, p. 38)

Xiaoming argues for a numerical value for accessibility mainly for the convenience and machine properties it would have but he states:

A quantitative numerical score would allow assessment

of change in web accessibility over time as well as comparison

between websites or between groups of websites. Instead of

an absolute measure of accessibility that categorizes websites

only as accessible or inaccessible, an assessment using the

metric would be able to answer the fundamental scientific question:

more or less accessible, compared to what? (Xiaoming,

2004, p. 38)

He cites a number of other benefits such a number might have

but he fails to convince the reader that a number would provide

useful information for making a site more accessible. If one

is to judge a site, perhaps his system would give a fairer

evaluation of a site than the existing and generally used checklist

provided by WCAG, which is what people usually refer to for

the dichotomous evaluation. He calls his metric the 'Web Accessibility

Barrier' score. (Xiaoming,

2004, p. 45)

The author was considering a numbering system some years

before the reported research. At the time, also working with WCAG,

it became clear that a simple accessible/not accessible statement

did not make sense. The idea was to develop a numbering system

that would give some indication of the characteristics of the

resource. The Platform for Internet Content Selection [PICS] rating idea was considered by the WCAG working

Group (Dardailler,

1999). It could have been used like the

original PICS ratings, with ten digits, each representing

a particular characteristic of the resource [PICS]. The

user could have set their PICS preferences on their browser,

and the browser would admit only resources that matched their

needs. It can be seen that this idea had merit, but it was

not as detailed as the AccessForAll solution now being

proposed.

Xiaoming's approach seems to have been more in line

with that taken by the EuroAccessibility group. The quality

mark approach, however constructed, does not seem to contribute

to accessibility for the user, or access to resources that

would be accessible to the user if not to everyone. It might

act as a motivation for content developers to be more careful

about the accessibility of their resources, but it is also

a source of revenue for those few organisations certified

to evaluate sites (in

some cases those who proposed the certification scheme) and

so there has been deep suspicion about it. Nevertheless, it is worthy of consideration.

Quality marks

In April 2004, the EuroAccessibility Workshop was held in

Copenhagen and came up with an annotated draft of the original

WCAG that attempted to make it testable (EuroAccessibility,

2004). One of the things they did was try to make WCAG testable: the plan from the April 30 2004 meeting was as follows (Table 1):

| Explanation |

Example |

| Take an original WCAG guideline |

Guideline 1. Provide equivalent alternatives to auditory and visual content. |

| and the original WCAG checkpoints |

1.1 Provide a text equivalent for every non-text element (e.g., via "alt", "longdesc",

or in element content). This includes: images, graphical representations of text

(including symbols), image map regions, animations (e.g., animated GIFs), applets

and programmatic objects, ascii art, frames, scripts, images used as list bullets,

spacers, graphical buttons, sounds (played with or without user interaction), stand-alone

audio files, audio tracks of video, and video. |

| and provide Clarification Points |

A text equivalent (or reference to a text equivalent) must be directly associated

with the element being described (via "alt", "longdesc", or from within the content

of the element itself). It is not unacceptable for a text equivalent to be provided

in any other manner i.e. an image being described from an adjacent paragraph |

| and testable statements |

Statement 1.1.1: All IMG elements must be given an 'alt' attribute. Text: Related

Technique: |

| |

Statement 1.1.2: The appropriate value for the text alternative given to each

IMG element depends on the use of the image.

etc |

| and provide a list of terms used for a glossary. |

|

Table 1: The unfinished plan to make WCAG testable (

EuroAccessibility,

2003)

There is no evidence the whole group managed to go much further

than to develop the statements. A small group received funding

to pursue their ideas as the CEN/ISSS WS/WAC developing a "CWA

on Specifications for a Complete European Web Accessibility

Certification Scheme and a Quality Mark" (CEN/ISSS

WS/WAC, 2006). There was, at the time, significant concern

with respect to this work. It was suspected by the author and others in the original EuroAccessibility group that the motivation for the work

was not simply improving the accessibility of the Web, but

also the creation of an industry, in circumstances when there

was doubt about the value of such an industry and fear it might

actually stifle better work. Such concerns were notified informally

(by private email) to the CEN process

and discussed informally in many other contexts.

In the current context, it is interesting

to note that the EuroAccessibility group were trying to find ways to insist that

a resource needs to have any necessary alternatives identified.

This is also considered important for AccessForAll

and shares the use of what might be

called metadata. In the former case, metadata would

be embedded in the resource and in the latter it can be independent

of it. The practical difference is that the EuroAccessibility

approach would not support third party, distributed or asynchronous

annotation as easily as does the AccessForAll approach. Nor

would it support the continuous improvement of the resource

by the addition of accessible components, which is a major

aspect of the AccessForAll approach.

The two approaches also differ fundamentally in that

the quality mark approach was intended to make a judgmental

statement about the resource whereas the AccessForAll approach

strictly avoids that.

A Practical Approach

In 2003, there was a wide-spread struggle with the question of

what could be done to improve the accessibility of the Web.

This was documented by the author in a note to the Australian Standards Sub-Committee

IT-019 (Appendix

9). One of

the major concerns was that the kind of metadata being proposed

at the time was mainly focused on compliance with WCAG and

therefore possibly not reliable. The author proposed using

descriptions encoded in the new Evaluation and Reporting Language

[EARL],

a technology for metadata that included information about when it was made, and by whom,

or what (in the case of automatic software evaluations). While many resource developers were still being encouraged

to make their own resources more accessible, it became

obvious to some that content authors were not reliable

in terms of accessibility. Attention was turning to the problem

of how to repair resources without access to the original files

and servers.

Currently, there is a substantial 'industry' in the

production of what are called 'alternate formats' or 'alternative

formats'. These are versions of materials that have been published in an

inaccessible form and converted to new formats for particular users,

for example, for students at a university. The need for this

work is probably increasing as the number of students requiring

special versions of content increases. It is an example of what in this research is known as post-production techniques

for increasing the accessibility of resources. It is, however, a human-intensive operation and only feasible for students with extreme needs because of that. The energy

it absorbs could be used to teach people to make better content

components ab initio, particularly by using better authoring tools, and many more poeple would benefit from the resulting accessibility.

The conversion of resources into alternate formats is usually

done on a case-by-case basis, and is subject to copyright in

many cases. Copyright issues are outside the scope of the research.

Suffice to say, then, that in most developed countries, there

is legislation that recognises certain people as having rights

associated with permanent disabilities they have. In Australia,

for example, a vision-impaired person who is a student can

register as having a medical or permanent disability and

therefore qualify for special copyright privileges. When the

resource is converted for them, it is supposed to be registered

with Copyright Australia Ltd if it is otherwise subject to

copyright. It seems from anecdotal evidence presented

in 2007 [OZeWAI 2007] that many resources have

not been properly registered because it is a cumbersome

process and those responsible try to avoid engaging in it.

What happens when a resource is so registered is that it becomes

discoverable for other users with permission to use such a

resource in an alternate format. This means that there is metadata

about the alternative. And that means its existing description

probably could be converted to provide AccessForAll metadata.

But even if this were so, the resource would still only be available

for some users.

The research calls for the development

of automated conversions

or adaptations that can be used by anyone, following the principles

of inclusion.

Exemplary post-production services and libraries

Post-production services are those that increase the accessibility of a resource after it has been published. In many cases, such services do not have any interaction with the original publishers of the resources, although this is not necessarily the case.

A good example of a post-production service is one that provides a human voice that reads aloud what is contained in a resource. Provision of a telephone number to allow a user to call and speak to an operator instead of struggling with a Web form is another example of such a service. Typically, educational institutions have units with people who reproduce resources in alternative formats. Specialists produce captions, often in alternative languages.

Recognising the problems caused by the vast amount of inaccessible material, Jeffrey Bigham and Richard Ladner (2007) are attacking the problem.

As a first step toward addressing these concerns, we introduce Accessmonkey, a common scripting framework that web users, web developers and web researchers can use to collaboratively improve accessibility. This framework advances the idea that Javascript and dynamic web content can be used to improve inaccessible content instead of being a cause of it. Using Accessmonkey, web users and developers on different platforms with potentially different goals can collaboratively make the web more accessible. In this paper we first present the Accessmonkey framework, describe three implementations of it that we have created and offer several example scripts that demonstrate its utility. We conclude by discussing future extensions of this work that will provide efficient access to scripts as users browse the web and allow non-technical users [to] be involved in creating scripts.

The AccessMonkey framework is a refinement of the GreaseMonkey framework, that is a refinement of the general Java framework. It allows for the adaptation of content after it has been published. The adapted content is stored separately from the original.

Earlier, Nevile and Kateli (2005) worked on the use of W3C's Annotea server for such a process. In that case, Annotea was used to store an alternative version of the content and instead of returning to the original server, the user could refer to the Annotea server for their adaptation. Instead of a special authoring environment, Nevile and Kateli used the WYSIWYG editor Amaya [Amaya], also from W3C.

Vision Australia (2008) has produced a Complex Table Markup Toolbar for increasing access to tabular information that is incorrectly encoded when published.

This toolbar is an add-on to FireFox which can be used to:

- Reveal 'headers' and 'id' complex data table mark-up.

- Create such mark-up either manually or automatically.

- Create a linear version of the data table content. (Vision Australia, 2008)

The National Center for Accessible Media at WGBH has produced the Media Access Generator [MAGpie] in two versions for creating captions and audio descriptions for rich media. MAGpie is free and there are a number of accessibility sites that recommend it and provide instructions for its use.

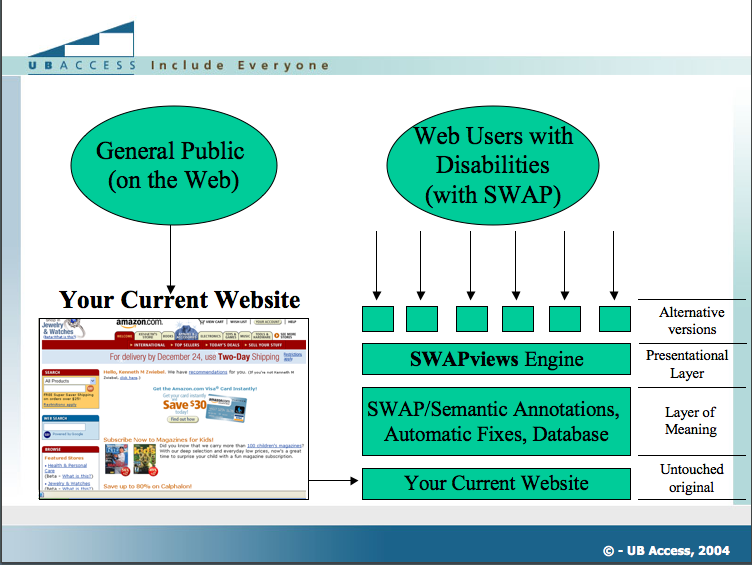

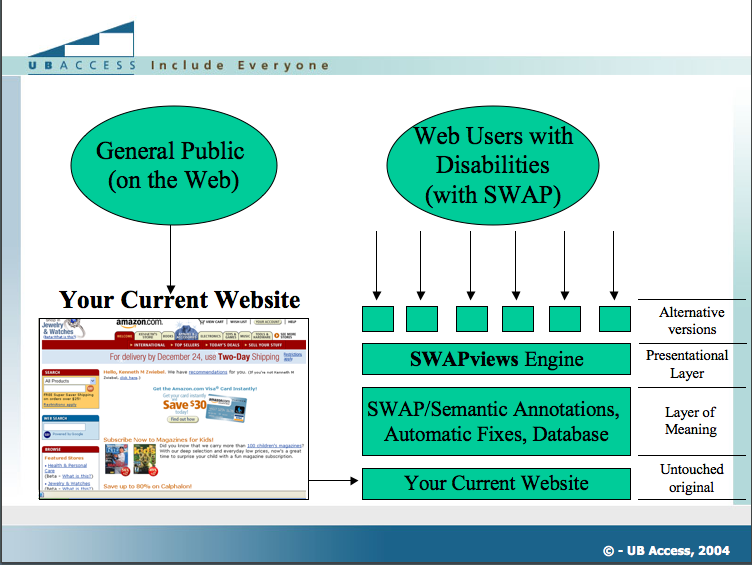

Perhaps one of the most ambitious tools for post-production accessibility work has been the Semantic Web Accessibility Platform of Lisa Seeman.

Figure 28: SWAP diagram from powerpoint slides...

http://www.w3.org/2004/06/DI-MCA-WS/presentations/originals/ubaccess.ppt

Figure 28 shows the layers associated with the SWAP application. The basic idea is that by enhancing the content with Semantic annotation, the system can enable different views of the same content for people with a range of different needs. The primary motivation for this work was the lack of support for people with dyslexia.

Most recently,

IBM launched on Tuesday an application that seeks to harness

the power and time of Internet users around the globe to make

the Web more accessible to the visually impaired....

Using the new IBM software users can report these problems

to a central database and ask for additional descriptive

text to be added to a site. Other Internet users that want

to contribute can then check the database, select one of

the submitted problems and "start fixing it" by

added text labels. The additional information isn't incorporated

into the original site's HTML code but into a metadata file

that is loaded each time a visually impaired user subsequently

visits the site. (Williams, 2008)

Chapter Summary

This chapter has shifted the focus from universal accessibility

of individual resources as originaly produced, to accessibility for individual users,

based on a combination of efforts, including both human and

machine input pst-production. It is the exploitation of thrid party effort and machine participation that locates such accessibility improvements more in the realm of Web 2.0 and Web 3.0 than was previously possible. Given the low levels of accessibility achieved in the first decade of Web publication based on responsibility for accessibility being with the original author alone, it is argued that such a strategy provides greater potential for increased accessibility. Management of the process, having a way of discovering and bringing the accessible components together to suit an individual user's profile of needs, is a significant requirement if this post-production accessibility is to be effective. It is contended that metadata can be used to provide such management and so it is a major focus of the research.

In the following chapters, metadata is defined, its use explained, the fundamental criteria for its effectiveness are explained, and it is shown how the AccessForAll approach uses metadata. As interoperability of metadata is crucial to its efficiency in this context, there is significant discussion of this aspect of metadata, and how it can be achieved.

Next -->

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.5 Australia License.

© 2008 Liddy Nevile

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.5 Australia License.

© 2008 Liddy Nevile